The OI’s excavation at Tell Edfu, Egypt. (Photo courtesy the Oriental Institute)

A brief history in pictures of some essential people, places, and treasures.

This article is part of the special feature “The OI at 100,” which commemorates the centennial celebration of the Oriental Institute.

In July 1919, this publication reported the establishment of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. “The ultimate aim of all its work,” the editors wrote, “will be to furnish a basis for a history of the origins and development of civilization.” The OI’s scholars would discover and examine millennia-old evidence that could illuminate collective human life in the past—and, by that means, our present lives.

With a century of exploration, excavation, scholarship, and education now behind it, the OI has achieved a deep history of its own, and a singular one.

Both a robust academic research center, creating knowledge about the earliest societies in the ancient Middle East, and a museum for the public, it holds treasures. Uniquely, most of them were excavated by the OI’s own archaeologists in its early years for study by experts and the education and marvel of all of us.

Those artifacts tell scholars much about the Egyptians, Babylonians, Persians, and other past peoples but also inspire and inform larger questions: How do humans build and structure their societies? How do people’s physical environments shape their ideas about mortality, nature, identity? And how are those ideas embodied in their material culture?

The OI’s home within a major research university has enabled still other kinds of contributions. Willard Libby’s development of radiocarbon dating in the 1940s relied on testing artifacts of known age from the OI’s collection. Its ancient language dictionaries—Assyrian, Hittite, Demotic—are massive, decades-long efforts requiring the concerted work of generations of scholars.

The people, excavations, and objects that shaped the OI over its first century are too numerous to present here exhaustively. In the following pages we highlight a few that just begin to capture its illustrious first hundred years.

Giants

Among the many archaeologists and scholars who made the OI what it is today are these pioneers.

James Henry Breasted

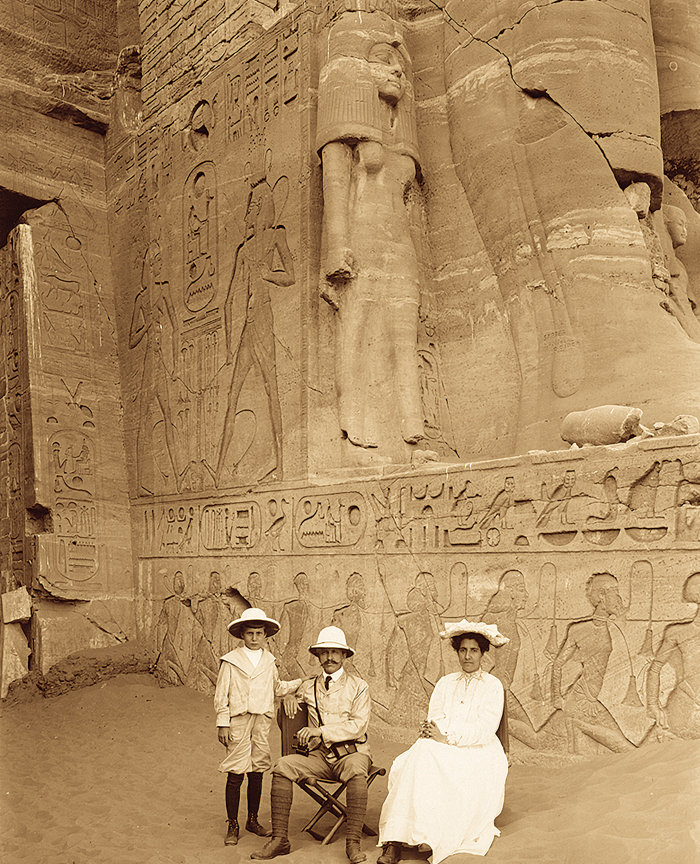

The first American to earn a PhD in Egyptology, James Henry Breasted (left, with his family) was a titan of the field. Alongside scholarly works, he wrote popular histories of Egypt and the ancient world, which sparked enduring public interest in Egyptology. Despite these successes, his greatest ambition, to form a research institute devoted to the ancient Middle East, remained unfulfilled until John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s 1919 gift created the Oriental Institute. Breasted wasted no time, traveling that year to Europe, Egypt, Iraq, Palestine, and Syria to explore and document ancient sites and acquire artifacts still held by the OI today, securing the institute’s—and his own—legacy.

Robert and Linda Braidwood

The marriage of Robert Braidwood, PhD’43, and Linda Schreiber, AM’46 (top right), in 1937 marked the beginning of a personal and intellectual partnership that would shape the field of prehistoric archaeology. Together, the Braidwoods documented the human shift from hunting and gathering to settled life. In 1947 they founded the OI’s Prehistoric Project, recruiting botanists, zoologists, and geologists and introducing interdisciplinary scientific methods that were previously unknown to archaeology. The Braidwoods discovered in southeastern Turkey the world’s oldest piece of cloth and some of the earliest known buildings. Collaborators until the end of their lives, Robert and Linda Braidwood died within hours of each other in 2003.

Robert McCormick Adams

In 1950 Robert McCormick Adams, PhB’47, AM’52, PhD’56 (right), joined the Braidwoods on an expedition to Iraq. (“I think he wanted to take along someone who could fix his cars,” Adams joked later.) The trip transformed Adams from an aspiring journalist into an archaeologist. Among the first to use aerial photography and satellite images in his work, Adams focused on the relationship between geography and civilization, arguing that how societies adapt to environmental change defines their trajectories. After serving as OI director and University provost, Adams went on to lead the Smithsonian Institution.

Places

Excavation sites past and present reveal settlement patterns, artifacts, and more.

Nippur

The Mesopotamian religious center Nippur lies in modern-day Iraq, 100 miles south of Baghdad. The seat of the supreme god Enlil and considered the bond between heaven and earth, Nippur was settled around 5000 BC and endured almost 6,000 years, remaining relatively protected from the region’s wars because of its religious and cultural significance. The OI first excavated the city’s trove of artifacts and clay tablets in 1948, focusing on the historically important religious quarter. In 1972, under the direction of McGuire Gibson, AM’64, PhD’68, professor of Mesopotamian archaeology, these efforts expanded to a residential part of the city before all work on the site ceased at the time of the first Gulf War. This year the OI returned to Nippur, restored its expedition compound, and prepared to fully resume excavating the city’s rich remains.

Tell Edfu

Ruins beneath ruins characterize the Egyptian archaeological site Tell Edfu, where the OI has worked since 2007 under the direction of Egyptologist Nadine Moeller. The site comprises the well-preserved Temple of Horus and a nearby settlement whose growth from a provincial town to a regional capital is recorded in archaeological layers going back to the third millennium BC. Last year Moeller’s team discovered a large villa of the early New Kingdom (1500–1450 BC), among whose features was a rare domestic shrine to the residents’ ancestors. The site illuminates broad patterns of ancient urban development.

Luxor

The OI’s Epigraphic Survey has been at work in Luxor, Egypt, for 95 consecutive seasons. The project’s epigraphers are joined by artists, photographers, librarians, conservators, stonemasons, and others in their work to record, in situ, the inscriptions and carvings that cover the vast reaches of Luxor’s temple and tomb walls. In that work they adhere to the collaborative, painstaking “Chicago House Method” refined over the decades since Breasted launched the survey. The method’s name refers to the University’s headquarters at Luxor, home to research and support staff, currently directed by research associate professor W. Raymond Johnson, PhD’92.

Persepolis

The tens of thousands of ancient tablets discovered in Persepolis in 1933 by OI archaeologists contained an overwhelming cache of records of the inner workings of the Achaemenid or Persian Empire of Darius I and his successors—but much of it is encrypted in the extinct Elamite language, known by few living scholars. To decipher the tablets, the OI brought them to Chicago on loan, where they have been studied by generations of scholars given the rare opportunity to learn about the empire from Persian sources. Most recently, Matthew Stolper, professor emeritus of Assyriology, and a team worked intensively to transliterate the tablets for further research prior to their upcoming return to Iran.

Artifacts

In the collection are objects that awe while telling us about the cultures that made them.

This copper alloy hand mirror, excavated from a tomb at Qustul in Egypt, dates from 1390–1352 BC. The figure of a young woman that forms the handle, about six inches high, is elaborately detailed, with earrings, a decorative collar, and even fingernails on her hands. Her curled hair suggests the goddess Hathor, associated with dance, love, music, and fertility. The disk she holds aloft was reflective when polished.

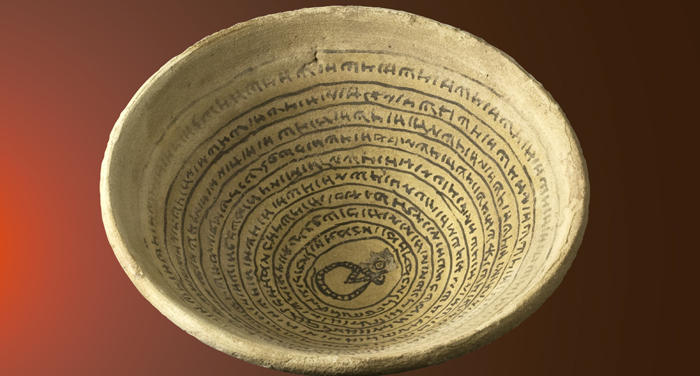

Excavated at Istakhr, just north of Persepolis, the six-inch inscribed clay bowl dates from AD 800–900. It boasts an early Islamic glazing technique thought to have been developed in imitation of Chinese ceramics. Opaque white wares like this were new to the Middle East at the time it was made. The cobalt blue inscription, in Arabic, is illegible.

During the Early Dynastic period (2900–2300 BC) in modern-day Iraq, this limestone plaque was part of a door-locking device. It’s decorated with a relief depicting a lavish banquet. The piece missing from the lower right is held by the National Museum of Iraq and shows two men wrestling.

This six-inch-tall portable Egyptian healing stela was used to treat ailments, possibly including animal bites, which were common in the ancient Middle East. Dating from the Ptolemaic period (fourth century BC), it depicts the sky god Horus stepping on crocodiles, signifying his domination over the beasts and hopefully auguring the patient’s recovery. Water was poured over the stela, then consumed by the patient.

Painted limestone with stone inlays for the eyes, these statues of a woman and man, researchers think, may portray ancestors of the statues’ owners. On their heads is bitumen, a tar-like adhesive, that once attached hair or headdresses. The substance also holds the eye inlays in place. Excavated in modern-day Syria, they date back 9,000 to 11,000 years ago to the early Neolithic period.