Russell Johnson, AM’15, PhD’19 (at far left, dressed as Jedi master Mace Windu), and his students pose for a costume-optional group photo on the last day of class. (Photography by Charissa Johnson)

In Star Wars and Religion, Russell Johnson, AM’15, PhD’19, uses the famous franchise to teach comparative religious ethics.

Not very long ago (spring quarter), in a classroom not very far away (Swift Hall 106), Russell Johnson, AM’15, PhD’19, is explaining Joseph Campbell’s notion of the hero’s journey. The words “Story Structure” are on the slide behind him, along with the Death Star and the Star Wars logo.

The old-fashioned wood-paneled lecture hall, filled with row after row of wooden desks, is more evocative of the classroom scenes in Indiana Jones, George Lucas’s other blockbuster series, than Star Wars. As in Dr. Jones’s classes, every seat is taken.

Star Wars and Religion, according to the course description, “is an introduction to comparative religious ethics, using the Star Wars film franchise as a point of reference to discuss different conceptions of heroism.” Lucas borrowed from a number of religious traditions—Buddhism, Christianity, Taoism—to create the world of Star Wars, he’s said in interviews. Johnson, a doctoral student in divinity (now PhD’19), designed the course to look more closely at those influences.

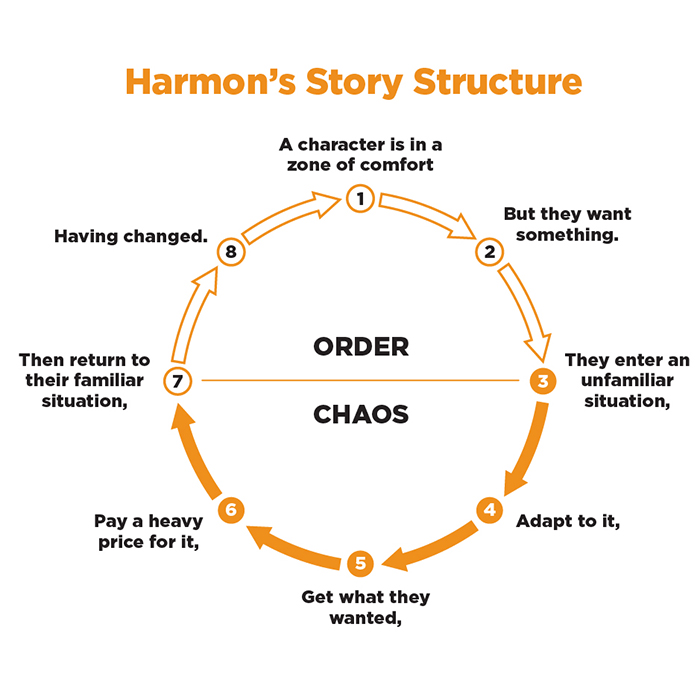

The 17-stage hero’s journey that mythologist Campbell developed is “weird and complicated,” Johnson tells the class. Although The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Pantheon Books, 1949) is an assigned text, today’s lecture focuses on the story circle, a simpler, eight-step version of Campbell’s monomyth created by screenwriter Dan Harmon in the early 2000s.

At the top of the circle, the character begins in a zone of comfort. They want something; they enter an unfamiliar situation; they adapt to it. At the bottom of the circle, they get what they want; they pay a heavy price for it; they return to their familiar situation. Back at the top again, the character has changed. “The audience has an instinctive taste” for stories structured like this, says Johnson.

“Harmon says everyone can have a story arc,” he continues. In the original Star Wars films, for example, Luke Skywalker has a story arc—but so does Han Solo. “C3PO has a really interesting arc,” Johnson points out; in fact he and R2D2 are the first characters we meet in the original 1977 film. “Maybe C3PO is the main hero.”

The change at the end of a story is what sets truly compelling narratives apart from, say, James Bond movies. “James Bond isn’t really a hero, because he doesn’t change,” says Johnson. “He’s the ultimate suave badass. He goes to all these fantastic-looking foreign countries. There’s cleverness, violence, and seduction. And at the end, he’s still the ultimate suave badass.”

Luke Skywalker: “What do you know about the Force?”

Rey: “It’s a power that Jedi have that lets them control people and make things float.”

Luke: “Impressive. Every word in that sentence was wrong.”

(from Star Wars: Episode VIII—The Last Jedi)

A few weeks later, Johnson has graded the students’ first papers, a four-page analysis of the Force in Episodes IV–VI, in response to Rey’s “wrong” definition. The students’ conceptions “were probably a lot more different than you would realize,” he tells the class. “The text supports a wide array of diverse interpretations, like the book we’re reading today.”

That book is the Tao te Ching, as translated by science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin. (The success of her widely praised version is all the more striking because Le Guin didn’t speak Chinese. She put it together based on earlier translations, the Chinese alphabet, and consultations with scholar J. P. Seaton.)

There’s a “general consensus among historians” that Jesus and Mohammad existed, Johnson explains, “but opinions are more skeptical on Laozi.” The name means “Old Master”; perhaps the text attributed to him came from a school of thinkers. “Textual evidence seems to support this theory.”

Johnson goes over a slide of key terms in Taoism: tao/dao means way; te is power, virtue, excellence, charismatic force; wu-wei is not-acting. “Clearly these concepts are rich enough to allow for a lot of different ways of being read,” he says. “It’s not that the Tao te Ching makes perfect sense in Chinese. If anything, Le Guin tightened it up a little bit.”

In the next class, Johnson lays out a multi-point argument that “the worldview of The Phantom Menace is to Taoism as Taco Bell is to Mexican food,” he says. “Which is to say, not authentic, but an effort has been made.”

For example, Taoist texts are critical of control and planning. Similarly, throughout Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999), Obi-wan Kenobi’s mentor Qui-gon Jinn (Liam Neeson), demonstrates calm acceptance of events, good or bad—“somewhat like the Taoist sage,” Johnson says. “Everyone else in the movie is stressed and worried about things, but not Qui-gon.”

Johnson gives numerous examples of dialogue that support his argument (including some from that polarizing figure, Jar Jar Binks—recently revealed, incredibly, to be Lucas’s favorite Star Wars character). When Obi-wan asks what might happen if their plan fails, Qui-gon responds, “Plan? Who said anything about a plan?” The end of the film shows both Anakin and Jar Jar “succeeding through failure,” echoing Taoist stories in which success is achieved by accident, by living in the moment rather than trying.

Every year, the Divinity School invites graduate students to pitch ideas for innovative undergraduate courses; Johnson’s was one of two that were chosen. In a typical comparative religion class, “one religion is presumed as the standard, usually Christianity,” he says. He wanted to try using “something non-religious as a standard of comparison for all of these.”

The course attracted some hard-core fans who showed their love by wearing Star Wars T-shirts to every class. There were also students who had never seen a single film. So Johnson set ground rules: only the films would be discussed, not television shows, books, or comics. “We had to exclude a lot of material within the canon,” he says, smiling at the similarity between fan terminology and religious language.

Johnson grew up watching the original trilogy on VHS. When the first prequel, The Phantom Menace, came out, “I, like the rest of America, saw it and was disappointed,” he says. His students, however, “have always lived in the world in which the prequels exist.” Johnson had to adjust to the younger generation’s terminology: “If you were around in 1977, Star Wars was just Star Wars.” But his students know the film by its new name, Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope, and they don’t refer to prequels or sequels, just Episodes I—VIII.

Johnson’s academic work focuses on communication ethics, especially during social conflict. The overlap between his dissertation and the Star Wars course, he says, is an interest in how different religious traditions conceive of good and evil.

Next year, Johnson begins a two-year postdoc in the Divinity School. He’ll teach classes in the Humanities Core as well as another course of his own design, Villains: Evil in Philosophy, Religion, and Film. The course—which features Cruella de Vil from One Hundred and One Dalmations (1961), Erik Killmonger from Black Panther (2018), the shark from Jaws (1975), and others—was partly inspired by a quote from screenwriter John Rogers: “You don’t really understand an antagonist until you understand why he’s a protagonist in his own version of the world.” That’s exactly what got Johnson interested in ethics and philosophy, he says: “the irony that tremendous suffering can result not from malice, but from people trying to do the right thing as they understand it.”

Asked for his favorite Star Wars film, Johnson says, “The Empire Strikes Back [1981] is the best of the Star Wars movies. That is not a controversial view.” But it also doesn’t answer the question. “Return of the Jedi [1983] was my favorite as a kid. It’s still my favorite,” he admits. “When I was a little kid, I liked the ewoks, it was funny and bright. I don’t know. I’m not 100 percent sure why. I just like it.”