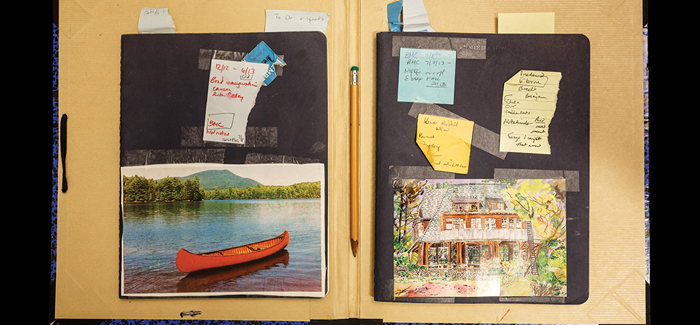

McLane’s notebooks are collages of thoughts and images. (Photography by Jason Smith)

Poet, critic, and scholar Maureen McLane argues for poetry that synthesizes, “with passion and knowledge,” what it means to be human.

The poet Maureen McLane, PhD’97, was warming up to a fiery, forceful rant. About poetic ideals and independence, the politics of imposing aesthetic standards on an art form (“I think it’s for shit, and I hope you quote me on that”), how T. S. Eliot is never going to be Downton Abbey, and how Garrison Keillor’s on-air poetry readings, which sometimes tend toward the mawkish, don’t, fundamentally, have much to do with the art itself. A few hours later, over martinis at a candlelit Japanese bar down the street, she would let the embers cool, step back, take the measure, parse the nuances. But for the moment, sitting in her tiny New York University office, which a malfunctioning heating system had turned into a sauna, she glowed hot thinking about the assertion—circulated by well-meaning public thinkers and endorsed by well-meaning others—that poetry ought to be a kind of chicken soup for America, a civic and social panacea: anodyne, innocuous, medicinal. The idea that people should read poetry because it will make them better citizens, and that poetry should reciprocate by being readily digestible. She noted that these idealized expectations do not weigh on other forms of art. “Poetry isn’t like vitamins,” McLane said. “It isn’t good for you. Read it or don’t read it. I feel that very passionately. If you want some kind of linguistic intensity in your life, then read poetry. But if you don’t feel a need for that, then you don’t feel a need for that.”

Not that she believes poetry shouldn’t be taught and disseminated and advocated for, or that fun and creative public programs shouldn’t be built around it. Or that reading poetry to children in day care wouldn’t be a good way of “extending the reach and feel of the language.” Or that adults, many of whom last read a poem in high school and remember it as “an annoying trigonometry problem they never want to look at again,” wouldn’t benefit from a renewed and less rigid exposure to poetry. She thinks, in fact, that it might change their lives. After all, for more than a decade, McLane—a scholar of British romanticism, whose third poetry collection, This Blue (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), came out in April—wrote book reviews for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Times, and the Boston Review, in part to say to readers: look, there’s poetry out there and it’s good. “Joseph Brodsky had this project when he was poet laureate,” she says, “to have the equivalent of a Gideon Bible in every hotel room, except it would be a collection of poems instead. And that seems to me kind of wonderful. That’s about putting stuff out there.”

No, what gets her exercised is the “public service announcement” approach to poetry, popularizing efforts that seek to “legislate” the art: telling poets what to write and telling people they should read it, with what she calls “supposedly democratic, actually Stalinistic diktats.” She recalls past editorials in Poetry magazine calling on poets to write more accessibly and to take up civic topics. “I want to destroy those sentences,” McLane says. “Poetry is a space of freedom, and the minute you begin administering it—” She stops midsentence, gathers herself, starts up again. “It’s like, come to it or don’t come to it. But it shouldn’t be shoved down your throat.” And another thing. “You know what? Our country is awash in accessible shit. Why would one want more? Actually, it would be much more interesting if there was more time for complexity. What would it mean to insist on, at least in education through high school, time given to complexity and difficulty?”

School was always McLane’s haven. Literature too, especially poetry, with its innate rhythms and rhymes and strange, kinetic entanglements of language. Here was a refuge from loneliness and alienation, a clarifying lens on the uncertainties of childhood, adolescence, adulthood. One of the first poems McLane remembers reading and internalizing was e. e. cummings’s “anyone lived in a pretty how town.” What drew her in first was the music lilting through its not-quite-syntax, the familiar words set down in a strange order: “anyone lived in a pretty how town / (with up so floating many bells down) / spring summer autumn winter / he sang his didn’t he danced his did.” If you keep listening, you start to hear other, deeper patterns: the contrast between love and unlove, innocence and experience, harmony and disharmony, conformity and independence. “Children guessed(but only a few / and down they forgot as up they grew / autumn winter spring summer) / that noone loved him more by more.” Decades later, the poem still resonates.

McLane grew up in the suburbs of Syracuse, New York. Her father was a librarian, her mother a teacher and guitarist, and their house was full of books and music. The oldest of three children, McLane sang in local choirs, took piano lessons, and played the organ in two churches. She wrote poems—“most of them, I’m sure, were pretty terrible”—and graduated from a large public high school full of smart, driven working-class kids. She went to Harvard, where she learned the art of close reading in classes with the famous poetry critic Helen Vendler and poet and essayist William Corbett. From there she went on to Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar. In 1991 McLane came to the University of Chicago.

It was in Hyde Park that she fell in with the poets of the Romantic period. At Harvard and Oxford and in high school, McLane had read mostly 20th-century poetry—modern, if not quite contemporary—and had begun exploring philosophy and psychoanalysis. Reading the Romantics was an awakening. She saw her own present-day questions about art and “the human” posed just as urgently in the words of Keats, Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, Wordsworth. “I realized that a lot of the things I was interested in in modernism have a prehistory going back to 1750, 1800.”

Among them, questions about poetry’s relevance and whether it was waning. Or whether it was lost. “People have been declaring poetry dead for over 200 years,” McLane says. Anxieties that today inspire calls for simpler, safer, easier-to-understand poems also plagued the British Romantics. At the turn of the 19th century, they felt their territory invaded by emerging natural and social sciences: chemistry, biology, moral philosophy, political economy. These new disciplines claimed to explain humanity in an overarching, comprehensive way that previously had belonged to the poets. “They were having to rethink the question of what is poetry and why bother with poetry,” McLane says. There was a growing sense that the sciences “were the master discourses,” she says, and that poetry “was going to be just this nice little entertaining thing on the side.”

Wordsworth’s response, in 1800, in his preface to Lyrical Ballads, was to plant a flag. “He says the knowledge of the poet is a general inheritance, and the poet is a man speaking to men and can speak to the human more broadly,” McLane says. Scientific knowledge, he claimed, was not so expansive and universal, but merely specific and individual. “Wordsworth was very much arguing that the poet’s job was to bind together with passion and knowledge all the disparate fields that humans are pursuing.” A counterintuitive concept to Americans today, who perceive science as general and poetry as personal and individual, but not so foreign in a era when epic poems were such a common art form that they inspired mock epics like Byron’s “Don Juan.” Still, McLane says, Wordsworth’s claim was “bold and idealizing,” even for its time. “And the fact that he’s making it—I mean, Milton didn’t have to make that claim, but Wordsworth did.”

This tug-of-war between poetry and science became the subject of McLane’s dissertation, and later her first scholarly book, Romanticism and the Human Sciences: Poetry, Population, and the Discourse of the Species (Cambridge University Press, 2000). “What’s interesting is that Wordsworth, Coleridge, those guys were really good friends with Humphry Davy, a major chemist of the period,” she says. Davy wrote poetry—Coleridge declared that he would have been “the first poet of his age,” had he not already been its “first chemist”—while Coleridge himself was forever experimenting with chemistry. Shelley launched silk hot air balloons into the sky over Devonshire. Erasmus Darwin, Charles’s grandfather, was a doctor and scientist but also a poet whose work Wordsworth admired. In his long poem “The Loves of the Plants,” Darwin imagined the stamen and pistil of a flower as a bride and groom. “And so there was still a dense interpenetration of worlds,” McLane says. Disciplines were not so separate. “But, you know, modernity’s about differentiation and specialization. And Wordsworth and Shelley in that period, they’re trying to fight against specialization.”

In her own way, McLane also resists specialization. “I tend to be a ‘both-and’ person,” she says, someone who feels most herself in the hybrid, the in-between. Her first full-time academic job, the one she holds now at NYU, came when she was 40; before that, her career was an intentional cobbling together of fellowships and lectureships and visiting faculty positions, which she occupied while also writing poetry and book reviews (for which she won a 2002 National Book Critics Circle award). After finishing her dissertation, she taught for two years as a Harper-Schmidt Fellow at Chicago. Then she spent almost a decade at Harvard, first as a member of its Society of Fellows, and then as a lecturer in its Committee on Degrees in History and Literature. Year by year she taught everything from 19th century British literature to American studies, a subject not directly in her field. She was perpetually reinventing her courses. “That’s where I actually am most comfortable,” she says, “these slightly marginal, liminal spaces, where Whitman says you’re both in and out of the game.”

Her work bears this out: she is a forager of forms, whose essays contain elements of poetry and whose poems are infused with scholarship. She writes in form and free verse—and sometimes both and neither all at once, a passing haiku, the echo of a ballad. Her subjects are both cosmic and terrestrial, intimate and public, domestic and civic. “The shapes of McLane’s sentences—real, complete sentences are rare here—often have a sculptural quality, shifting in both form and meaning as we peruse them,” wrote Tess Taylor, reviewing McLane’s first two poetry collections for the Boston Review. Elsewhere Taylor observes, “McLane’s poems express a wish not for wholeness, but for the sufficiency of what little we can hold on to.” Similar strains run through This Blue, a book whose poems ruminate often on the idea of time and finitude, and on a world that remains ancient even as it’s made new, forever broken while also full of fresh possibilities.

Her notebooks, a kind of cauldron where new poems percolate, are collages of book titles (both read and to be read), grocery lists, snatches of overheard conversations, quotes from anything and everything McLane happens to be reading. There are shards of her own poems, partial stanzas, and passing thoughts. Notes and sketches from art exhibits. Doodles. The covers of McLane’s notebooks look like literal collages, with postcards from travel and writing retreats taped to the front. “They’re this really weird hybrid work where they’re somewhere between commonplace books and draft spaces,” she says.

Even the title “poet” feels narrow to her; citing Shelley’s “A Defence of Poetry,” she prefers a less rigid and specific term: “maker.” “Shelley does this thing,” she says, “where he says there’s poetry in the restricted sense, what most of you would call poetry, these little versified things, whether they’re lyrics or epics or epyllions”—shorter narrative poems. But, like Wordsworth in the preface to Lyrical Ballads, Shelley also claimed more territory for poetry, defining it as something bigger, wider, more primary. “He says poetry in the general sense is any kind of making.” Plato, Jesus, Dante, the scientist and philosopher Francis Bacon: Shelley claims them all for poetry. Poetry, in Shelley’s argument, can be anything and everything. “Which he legitimizes by thinking about poetry etymologically in the Greek: poiesis.” The root of the word “poetry” is an ancient Greek verb that means “to make.”

As a maker, she says, “you’re in a field of affinity with other people who want to make things”: composers, choreographers, filmmakers. “And your medium is language in a certain key.” She returns to Shelley again: “As Shelley said, ‘in the youth of the world,’ man would dance and sing, and out of that gestural thing came formal music and formal poetry.” In other words, human beings have an inborn propensity to move rhythmically and talk interestingly, and those give birth to the arts. “That’s a more capacious way of thinking about poetry anthropologically,” McLane says. “It’s like, what does the species do? It does this kind of thing. And one of these things is to make poems.”

The book that perhaps most fully illustrates McLane’s approach to poetry isn’t actually a book of poems—and yet it also somehow is. In 2012 she published My Poets (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), a collection of autobiographical essays that combines memoir with criticism and with poetry itself. A finalist for a National Book Critics Circle award, My Poets feels experimental and old-fashioned at once. It traces McLane’s reading life from early adulthood (those close-reading classes with Vendler and Corbett) onward as it coincided with her private life. She goes to college and then to Europe; she marries, and her marriage breaks apart when she falls in love with someone else, a woman. Her life moves on.

These personal stories are not so much told as darted toward in oblique and luminous flashes, and enmeshed within them are meditations on poetry. Marianne Moore sees McLane through her wedding, and Louise Glück sustains her through the divorce. Emily Dickinson, a poet of the Civil War and of terror, who wrote “My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun—,” helps McLane make sense of 9/11 and its aftermath. Amid the glut of mythmaking that engulfed the country after the trauma of the attacks, the stories and images that slid “too easily into a banal repertoire, commodified shock,” McLane finds clarity and comfort in Dickinson’s “ceaseless instinct for negation, distinction, refinement, annihilation.”

There is mutual enrichment in McLane’s lived experience and her analysis of the poets she read as she lived it; this is a book not only about how poetry has informed her life but also about how her life has informed her understanding of poetry. A pair of centos, poems made up entirely of lines borrowed from other poems, lie tucked between chapters, offering their own insights from McLane’s intermingled life and library. An abecedary called “My Translated” presents a songlike alphabetical catalog of works in translation that have been meaningful to her: Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, Dorothy Sayers’s Dante, David Grene’s Sophocles, David Hinton’s Wang Wei. There are catechisms, playfully allusive Q&As constructed from lines of verse. At times McLane addresses her remembered self as “you,” bringing a simultaneous distance and immediacy to her recollections.

McLane’s prose tumbles in and out of other poets’ verses, other writers’ words and worlds, sometimes speaking through them, braiding her thoughts and emotions with theirs. She writes a chapter on Elizabeth Bishop in the voice of Gertrude Stein, mimicking Stein’s circular rhetoric and clipped and comma-less declarations. McLane’s poetic assessments—relentless and affecting and incantatory, both whimsical and serious—seem to not just dissect but devour. And they are as revealing as any direct detail of autobiography.

Engaged to be married and increasingly uncertain about whether it is what she wants, McLane reads Marianne Moore’s poem “Marriage,” a conversation between Adam and Eve that amplifies two vastly different perspectives on the institution of marriage. To Adam it is commendable “as a fine art, as an experiment, / a duty or as merely recreation.” But Eve calls it, less rosily, “This butterfly, / this waterfly, this nomad / that has ‘proposed / to settle on my hand for life.’” McLane writes: “A glorious ‘he says, she says,’ exchange unfolds, as if Moore were staging her own George Cukor comedy. Moore gives us two beautiful subjects speaking past each other. As Freud knew, as Lacan knew, as one is given by life to know: one speaks past as well as to the other.” McLane’s fiancé is kind and intelligent and “seemingly open to every thought, however disturbing,” but something’s still not right. She’s ambivalent about marrying and later comes to realize that she is in love with someone else, even though she is “not it would seem out of love” with her fiancé. “This was unwieldy,” she writes, swerving back toward Moore’s poem. “It was a contradiction, a flaw in the world, unencompassable, ‘the central flaw / in that first crystal-fine experiment,’ and everything shattered.”

Throughout the book there is the palpable ache of McLane’s ever becoming: an adult, a poet, a writer, a reader, a thinker, an American, a self.