Share your doodles with the Magazine.

Doodling is the sincerest form of flattery.

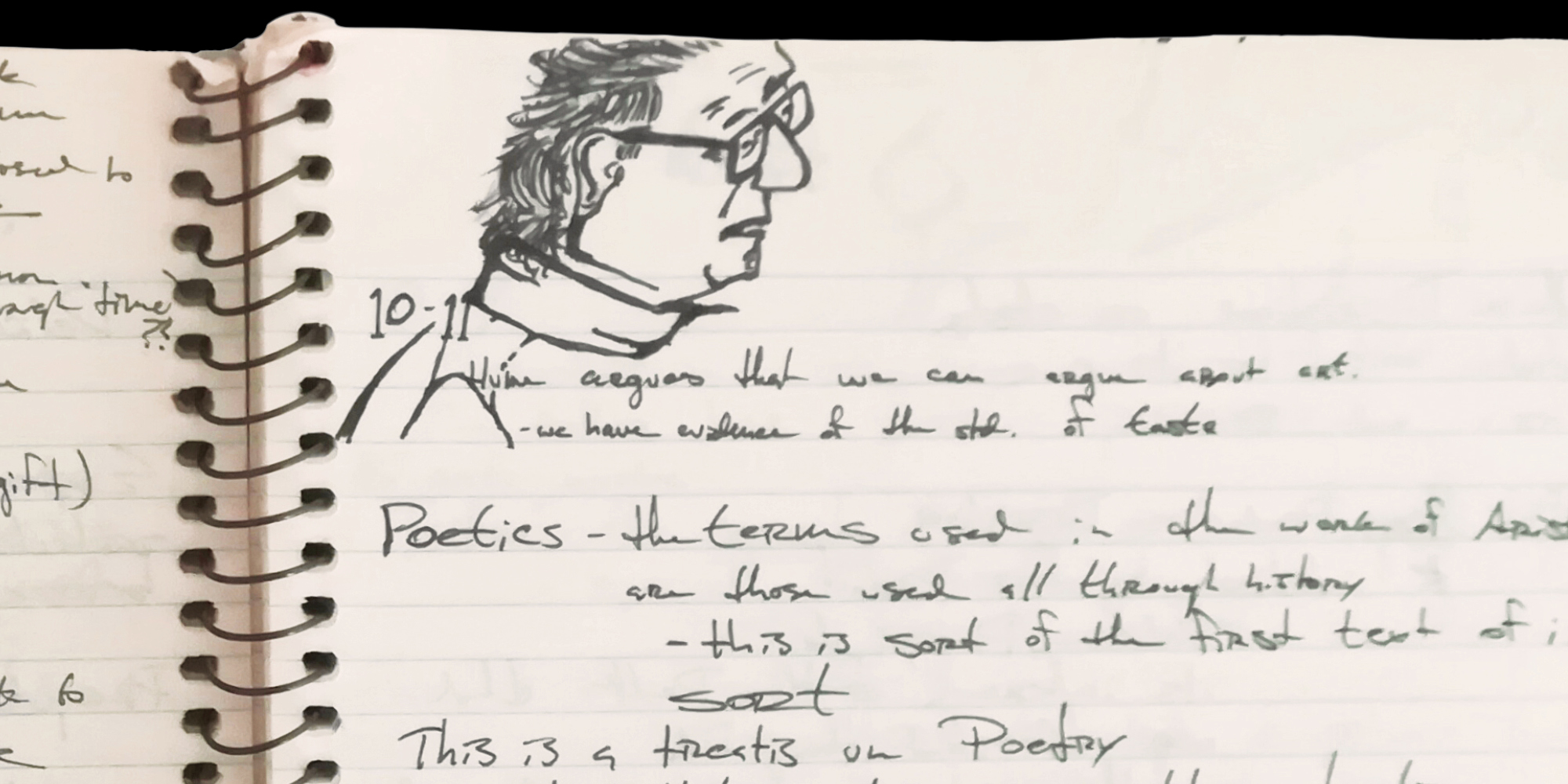

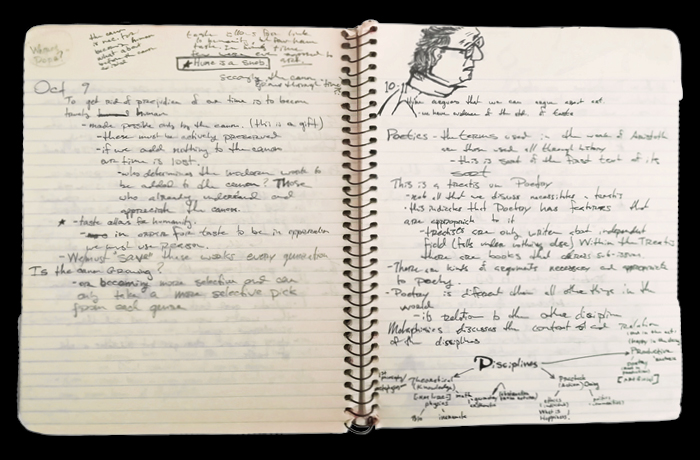

In his College classes, Benjamin Lorch, AB’93, AM’04, often surrounded his notes with doodles, and the more he enjoyed his professors, the better the chances his marginalia included their likenesses. Among those teachers Lorch really liked—a far from unique sentiment among College alumni—was Herman Sinaiko, AB’47, PhD’61 (1929–2011).

Shown here are Lorch’s notes from Modes of Criticism, where Sinaiko impressed on the students taking the General Studies in the Humanities course that “each discipline, each science, and each way of thinking has its own language, logic, lessons, and learnings,” Lorch recalls. His notes reveal that under discussion that fall day in 1989 was Aristotle’s Poetics.

Have you saved your own course notes, and do they contain any notable doodles? Scan and send them to us at uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu and we’ll share a selection on our website.

Was it routine for you to sketch your teachers?

Yes. I drew a lot of stuff in the margins of my notebooks. Psychedelic, melting space stuff and people in my courses. There were so many thoughts being pumped through those classrooms that some running visual commentary seemed only appropriate.

How did you like Sinaiko’s class?

I liked the class very much. And I liked Sinaiko very much. Had I not, the sketch would not have come out the way it did.

What has stuck with you from that class?

There is a line of argument captured in the notes that explains that each discipline, each science, and each way of thinking has its own language, logic, lessons, and learnings. Only when fully engaged within a discipline can we truly know and feel its powers to describe and reveal. Sinaiko taught me how Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, and Nietzsche wrestled with the fundamental questions of our humanity just as much as the Chicago blues taught me about love, loss, and race in America. The key was to understand the disciplines of thoughts, feelings, and expressions.

What do you remember most about Sinaiko?

I remember Sinaiko’s kindness. And I remember his close engagement with the texts we studied. He cared and he was a master of conversation in the classroom. I took an incomplete in his class and that never disturbed him. He was always supportive when I went to see him in office hours. He had a daybed in his office and sometimes it seems that I interrupted a small cat nap. He would splash water on his face, make no apologies—nor should he!—and say, “Let’s talk. How can I help you?” When I was writing that paper several quarters later to graduate on time, he helped me revive the issues of the course and put the paper on its feet. We were back in conversation again with Socrates, so the time did not matter. These were issues without deadlines.

Did you agree—as recorded in your notes—that Hume was a snob?

Yes. But I also think everyone should be a snob about the things that truly matter to them. Snobbery (read: enthusiasm) should be shared with others as an inclusive appreciation of life and its wonders, not a derisive insider/outsider device. I think Hume would agree: share the love!

Any footnotes you’d like to add?

When I read these notes I see how influential on me this course and so many others like it were. Long Live the Core!