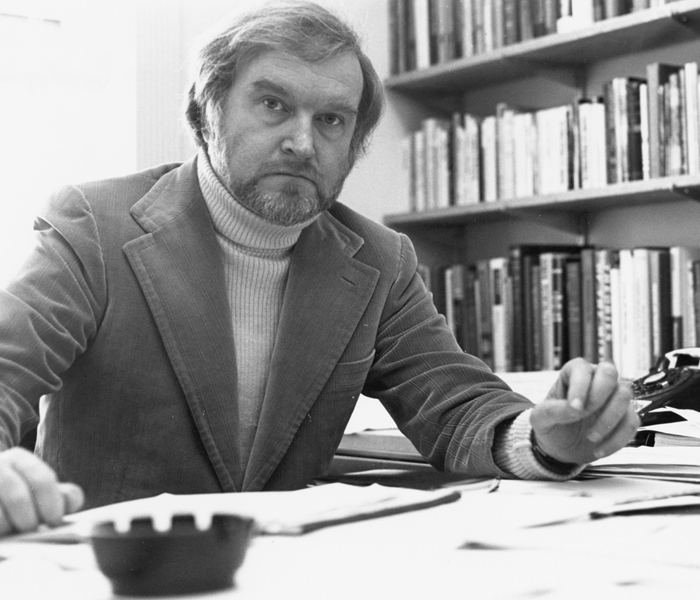

As a young man Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, AB’60, PhD’65, derived flow from rock climbing. (Photo courtesy Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi)

In 1975 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, AB’60, PhD’65, came up with the notion of autotelic experience—better known as flow. Forty-five years later, we’re still talking about it.

At a press conference a few days before Super Bowl XXVII in 1993, Dallas Cowboys coach Jimmy Johnson did something strange.

He talked about Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (Harper & Row, 1990), telling reporters it had helped him train the team. The book, by then UChicago psychology professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, AB’60, PhD’65, scrutinized flow experiences: moments when you are so focused on a challenging activity—making art, performing surgery, playing a sport—that time seems to stop and all other thoughts drop away.

On Super Bowl Sunday the Cowboys crushed the Buffalo Bills 52–17. “Get used to the Dallas Cowboys, folks, because they’re going to be with us for a long time,” Sports Illustrated observed. Indeed, the Cowboys went on to win two more Super Bowls, in 1994 and 1996; meanwhile Csikszentmihalyi’s ideas had been permanently launched into popular culture. During the 1990s, politicians Newt Gingrich, Bill Clinton, and Tony Blair all cited the book as an influence. (It’s tempting to indulge in a little counterfactualism and wonder what might have happened if the Cowboys had lost.)

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi—pronounced, as he explains it, ME-High Chick-SENT-Me-High—published his first book on flow in 1975. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play (Jossey-Bass Publishers), was “generally ignored in the professional literature,” Csikszentmihalyi wrote in the preface to the 25th anniversary edition. But interest in the notion of flow grew year by year, he wrote, and it’s now “a technical term in many languages, from Swedish to Japanese, Hungarian, Spanish, and Chinese.”

In Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, Csikszentmihalyi and a team of graduate student researchers studied four activities: chess, rock climbing, “rock dancing” (meaning freeform dancing to rock music), and surgery. Except for surgery, all of these are “unproductive,” according to Csikszentmihalyi: they are forms of adult play. He hoped by studying play, he could learn how work could be made more enjoyable.

Csikszentmihalyi’s original term was autotelic experiences, from the Greek for self (auto) and goal or purpose (telos)—that is, activities you want to do for their own sake, as opposed to exotelic activities done for a reward. (In passing, Csikszentmihalyi also noted the existence of autotelic personalities, people who can enjoy almost any activity.) During team meetings with his researchers, without really intending to, they shifted to saying flow instead.

The word was borrowed from an interview with one of their subjects, a poet and mountain climber: “The act of writing justifies poetry. Climbing is the same: recognizing that you are a flow. The purpose of the flow is to keep on flowing, not looking for a peak or utopia but staying in the flow.” Reflecting 25 years later, Csikszentmihalyi wrote, “If we had continued to use the precise but cumbersome autotelic experience, few people outside the academic community would have paid attention.”

Flow was not a universal experience among his research subjects, Csikszentmihalyi acknowledged. Of the climbers in Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, for example, only nine of 30 consistently reported flow experiences, and several dismissed the idea entirely:

“Bullshit.”

“I just don’t feel that.”

“I think somebody must be trying to be spectacular.”

Csíkszentmihályi Mihály (as his name is written in Hungarian) was born in 1934 in Fiume, then the Kingdom of Italy, now Rijeka, Croatia.

In the 2004 TED Talk Flow, The Secret to Happiness—which has been viewed more than five million times—Csikszentmihalyi weaves an origin story with many strands. Growing up during World War II, he was disillusioned by the failures of the adults around him, who seemed unable to “withstand the tragedies that the war visited on them.” Elsewhere, Csikszentmihalyi has observed that when he was in a prison camp as a ten-year-old, his only moments of joy came while playing chess.

As a teenager, he studied philosophy, art, and religion, seeking to understand what made life worth living. One evening, since he had no money to see a movie, he decided to attend a free lecture on flying saucers. The speaker, a psychologist, explained that “the psyche of the Europeans had been traumatized by the war, and now they’re projecting flying saucers into the sky.” Impressed, Csikszentmihalyi decided to read the man’s books. “And that was Carl Jung,” he says, as the TED audience gasps.

In 1956 Csikszentmihalyi came to the United States to study psychology. Csikszentmihalyi spoke little English (he was fluent in Hungarian, German, and Italian), but he managed to pass the entrance exam for the Chicago branch of the University of Illinois. Later he transferred to UChicago—working nights all the while—where he studied with philosopher Hannah Arendt and Mircea Eliade, historian of religions.

After finishing his bachelor’s degree he was accepted into the Committee on Social Thought, “the academic equivalent of St. Peter beckoning you through the pearly gates,” he recalled wistfully in the preface to Beyond Boredom and Anxiety. But it didn’t offer funding. Instead he enrolled in the Committee on Human Development, which gave him a fellowship.

His doctoral thesis focused on creativity. As he observed painters making paintings, Csikszentmihalyi was intrigued by “the almost trancelike state they entered when the work was going well.” According to the behavioral psychology then in vogue, their primary motivation should have been the reward of a finished painting. So why, Csikszentmihalyi wondered, were they so indifferent to their completed work? Why did they immediately want to start something new?

Csikszentmihalyi’s first teaching job after finishing his doctorate was at Lake Forest College. He returned to UChicago’s Committee on Human Development in 1970—giving up his tenure at Lake Forest to do so. Soon afterward he won funding for a study of autotelic experiences, which became Beyond Boredom and Anxiety.

The title came from Csikszentmihalyi’s model of the flow state: he placed flow between boredom (which occurs when an activity is too easy) and anxiety (when an activity is too difficult). Flow results from the perfect match of challenge and skill.

Many more books on flow followed, including Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (Harper Collins, 1996), Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life (Basic Books, 1997), and Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning (Viking, 2003).

Csikszentmihalyi’s initial research on flow was based on interviews: subjects had to try to recall how they felt during self-defined peak experiences. When pagers became popular, he came up with the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) to get more accurate data. Eight times a day, at random moments, research subjects were paged. After each page, they wrote down what they were doing and how they were feeling. Using ESM, Csikszentmihalyi discovered “a strange inner conflict”: the data showed that his research subjects were most likely to be in flow at work. Nonetheless they preferred leisure.

Many people, Csikszentmihalyi argues in Flow, have no idea how to enjoy their free time, choosing passive, escapist pastimes (he is particularly critical of television watching) rather than hobbies that demand skill. “Instead of using our physical and mental resources to experience flow,” he notes, “most of us spend many hours each week watching celebrated athletes playing in enormous stadiums.” The Dallas Cowboys may be experiencing flow, but the millions of couch potatoes watching them probably are not.

Unfortunately, none of Csikszentmihalyi’s books—not even the mass-market paperbacks—spell out clearly how to get into flow if you don’t already know. “A joyful life is an individual creation that cannot be copied from a recipe,” he writes in Flow. But its general principles, along with examples of people who achieve flow often, “should be enough information to make possible the transition from theory to practice.”

Csikszentmihalyi retired from the University in 1999, but he’s still teaching. At Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California, he founded the Quality of Life Research Center, which focuses on positive psychology. “This is all voluntary. I can stop any time,” says Csikszentmihalyi, who’s now 84. But teaching and working with graduate students “is still a major source of flow.”

As a young man, he says, “I do think that I experienced flow before I understood what it was,” while rock climbing, cooking, painting, and playing chess. As he’s gotten older, he’s had to make adaptations. He still enjoys hiking, but the difficult, dangerous climbing that used to put him in a flow state has been impossible for many decades. “I suppose it depends on the person,” Csikszentmihalyi says. “I get flow from more things, but not as deeply as before.”