The COVID-19 quarantine tier of Cook County Jail, where Miller once worked as a chaplain. (Zbigniew Bzdak/Chicago Tribune/TNS)

Punishment doesn’t end after incarceration, writes Crown Family School associate professor Reuben Jonathan Miller, AM’07.

There’s a figure Reuben Jonathan Miller often cites when talking about life after incarceration: 45,000. That’s the approximate number of federal, state, and local laws, policies, and sanctions regulating where Americans returning from jail and prison can live and work, who they can live with, and how they can spend their time. Homecoming is a gift and an obstacle course of almost unimaginable complexity, one in which a single error may come at the cost of freedom.

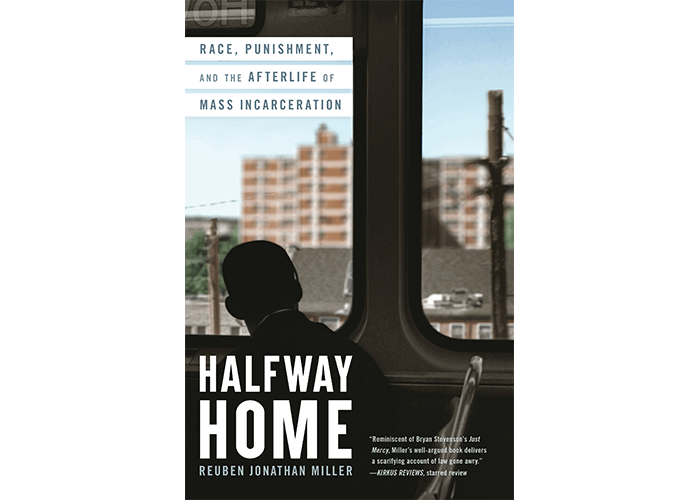

Miller, AM’07, an associate professor at the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, has spent the past 15 years studying mass incarceration and its reverberations, but he has lived with the problem for much longer, as he discusses in his book Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration (Little, Brown, 2021): “I simply could not write this as some detached observer because I am close to this book, and I am close to the people in it.” His father and two of his brothers have all served time.

Halfway Home reflects Miller’s constellation of experiences with the prison industrial complex, melding ethnographic research with narrative and autobiography. This approach allowed him to show not just the fact of social exclusion for the formerly incarcerated but also the feeling of it—and that, he says, “allows the reader to assess whether or not I’m right.”

The book deepens and extends an argument Miller has made throughout his academic career: that mass incarceration and mass supervision (that is, probation and parole) have created a separate class of citizens who are, as he has described it, “amputate[d] … from the social body.” The disconnection deprives them of the things they most urgently need after release—income, shelter, community, and safety.

The idea that people leaving jail and prison need safety too is one that our society resists, Miller says. In the months since Halfway Home was published to wide acclaim, he’s been invited to talk with policy makers around the country about how to address people’s postincarceration needs. “I’m happy to and grateful for the opportunity to,” he says. “But the thing that I keep seeing that’s absent is a view of these people as vulnerable and in need of protection.” Individuals who commit crimes, he points out, are also victimized at very high rates.

Many of the formerly incarcerated people Miller follows in Halfway Home held the dual identity of perpetrator and victim, though they were reluctant to acknowledge it—they could discuss their own crimes more easily than those committed against them. But as Miller got to know them better, they divulged life stories forged in violence, including, commonly, childhood physical or sexual abuse.

A central theme of Halfway Home is the violence incarceration itself does to families. Half of the people in prison have minor children, and many incarcerated women are their children’s primary caregivers. Miller describes the toll of imprisonment in these cases as “family separation,” language that he says intentionally evokes the outcry surrounding immigration policies separating parents from children at the US border. He was glad to see the outrage “in relation to these precious children,” and wanted to show that family separation has deep roots elsewhere in American life—for children of enslaved people, for indigenous children, and today for children of incarcerated parents. “What does it mean to have done this so much that it’s routine?” Miller asks.

And routine it is—along with nearly everything about incarceration and supervision. Another statistic that Miller cites often is the number of Americans with a family member who has been incarcerated: one in two. “So this story is an American story,” he says.

Rewriting it will not be simple. “Punishment looks like the cultures in which it’s embedded,” Miller argues. “The reason why we have the scale of incarceration that we do is because we think about the Other in the way that we do.”

He’s studied incarceration abroad, including in Serbia where prisons (while plagued by their own serious problems) are less socially isolated than in the United States. Privileges such as intimate visits or family visits outside the prison are more common, reflecting cultural beliefs around the importance of sexuality and togetherness. A different justice system emerges from a different set of assumptions about humanity and who’s allowed to claim it.

That doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be accountability. It’s essential for people who caused harm “to look harm right in the face,” Miller argues. That’s part of why he is drawn to restorative justice, an approach that emphasizes repairing the harm caused by crime, sometimes through meetings between victims, perpetrators, and other affected community members.

“There are a number of organizations that do this beautifully,” he says, citing one that brings together mothers whose children are incarcerated for crimes, including gun violence, and mothers whose children died from gun violence. “That’s a blueprint we can borrow from.”—S. A.

In the below passages from Halfway Home, Miller explores the toll of incarceration on family relationships, including his own. He tells the story of one of his research participants, Jimmy (a pseudonym), who is out of prison after a three-year sentence for grand larceny. Jimmy has been living intermittently with his on-and-off girlfriend, Cynthia, but feels conflicted: he knows he doesn’t love her, but he has no place else to go.

In the below passages from Halfway Home, Miller explores the toll of incarceration on family relationships, including his own. He tells the story of one of his research participants, Jimmy (a pseudonym), who is out of prison after a three-year sentence for grand larceny. Jimmy has been living intermittently with his on-and-off girlfriend, Cynthia, but feels conflicted: he knows he doesn’t love her, but he has no place else to go.

When was the last time you saw your mother?” I asked Jimmy as I sat across the table from him at the Coney Island diner.

“I don’t really come around like that,” he replied. Jimmy certainly needed his mother. He was homeless. He was in drug treatment, doing his best to stay clean and sober. And Jimmy was Ruth’s baby, the youngest of her five children. She would have taken him in. But he and Ruth both knew that she would be evicted if she did. He’d decided to avoid her because she wanted to help.

“I understand,” I said. I asked about Cynthia again. “Too much drama,” he told me.

We finished the meal as he talked about his job hunt and his relationship with his parole officer and how his treatment was going and how it felt to be “free.” I paid the bill and handed Jimmy the bus card and the forty dollars I gave him at the completion of each interview. I dropped Jimmy off at the construction site and made my way home.

The next time we connected, Jimmy had changed his tune about Cynthia. He was sleeping at her house more often, away from the drafty, sometimes damp, almost always too hot or too cold buildings he gutted. And he told me that her sister had stopped insulting him. They got along better. I wondered why. It turned out Cynthia had had a stroke, her fifth, and was in what Jimmy called a convalescent home. This made him sad. He was no more attracted to her than he had been a few months before, but now they were making plans to get married. Marriage, he said, was the only way he could secure an apartment. He also said he wanted to help Cynthia make decisions about her medical care. But Jimmy wasn’t happy. He described the upcoming marriage as a debt. “She stuck with me in prison. I’ll stick with her now.”

In a moment of reflection about his life and his relationships, Jimmy said, “I feel needy.” I asked if he thought his relationships would have been the same had he not gone to prison. Jimmy sipped the last of his weak diner coffee and finished chewing his toast. “No,” he said, signaling the end of our conversation.

In a lecture I gave at a legal aid convention, I talked about citizenship in the supervised society, where thousands of laws dictated where and with whom a previously incarcerated person could work or live and what it meant for the law to come between a person who has been incarcerated and the people he cared for most. I discussed how law and policy granted many kinds of people immense power over the lives of people with criminal records. I told Jimmy’s story about Cynthia, whom he slept with but didn’t love, the woman he was going to marry out of a sense of obligation, or need, or desperation—the one to whom he owed a debt. And I talked about the way his sister treated him and how he had to rely on people he barely knew just to meet his basic needs. I talked about what an economy of favors looked like and, more important, what it felt like. How it showed up in Jimmy’s life. How it changed his perception of himself. How the power that others had over him changed the nature of his relationships.

An attorney, flanked by two colleagues who were also public defenders, came up to speak with me at the end of my talk. Sheila, who did most of the talking, had worked for years in housing law, representing clients in central Illinois, almost all of whom were facing eviction. Many had criminal records. Many more had children who had done time. “In the private sector,” she said, “if a landlord has decent housing to provide, they probably won’t even rent to someone with a criminal record. . . . But there are plenty of landlords who do, [and they] rent to people with extensive records or people [they know who are involved in] criminal activities. ... But often times,” she said, “those places aren’t fit for people to really live in.”

I had heard as much from dozens of previously incarcerated people, that it was nearly impossible for them to find a place to live regardless of their credit or income. And they told me the conditions in the apartments they found were unbearable. Vermin. Rusty water. Broken appliances. Lights and electric sockets that didn’t work. Some places were dangerous in other ways. They were next to crack houses, or they were in neighborhoods where the police rode through to make arrests but didn’t have a real presence otherwise. The schools were the worst in their districts. Nothing ever worked. The landlords abused their rights, and the tenants had little or no recourse.

Sheila said, “I had this client a few years back. This was my first day in a new office. We have things known as emergency cases. You drop everything,” she explained. She represented a tenant who had withheld his rent, citing the conditions of the unit.

“The landlord turned off water, utilities, all that madness,” she said. “To me and everyone else [who works in tenants’ rights,] that’s what we call a lockout emergency. [You] run to the courthouse, get a restraining order,” she said. “It’s illegal for a landlord to shut off the utilities, even for nonpayment.” It was called a breach of the warranty of habitability, she told me.

Landlords have a legal obligation to ensure a unit is habitable. No one could reasonably be expected to live in a place with no running water.

“The only defense,” Sheila said, “was that my client had an extensive record. Professor Miller!” she said, raising her voice. “I mean the record was ex-ten-sive.” She assured me his convictions were “awful” without saying what they were. “But he’s still a person,” she said. “He still has rights.”

The case went on for over a year. Eventually, there was a ruling. Tenants have rights, and Illinois, according to many landlords I’ve spoken with, is a tenant-friendly state. The landlord was in the wrong and the client had a history of paying his rent on time. But her client had a record.

“You can always use those records to impute credibility,” Sheila told me. “The judge found he wasn’t credible,” she said, meaning that after a year in court and a clear violation of her tenant’s rights, the client didn’t have the grounds to bring a lawsuit because he had a record. The conditions of the apartment and the actions of the landlord didn’t matter in this case. In fact, Sheila said, “he wants me sanctioned for representing someone not worthy of legal aid assistance!”

We spoke again a few months later, this time over the phone. “I had this epiphany,” she said. “I care about my clients. I want them to have housing and be content. But sometimes we’ll prepare an agreement that says, ‘So-and-so’—meaning a loved one with a record—‘is not allowed to live here. So-and-so is barred from the premises.’ But quite frankly, where is So-and-so supposed to go?”

Sheila asked if she was part of the problem. With so much at risk, sometimes telling a mother to evict her child was the best legal advice she could give.

I was twenty-eight when I met my father. I’d heard his voice maybe once before, but we hadn’t had a conversation. I learned who he was only through an acquaintance’s chance encounter with someone else. I got a phone call from a woman who went to my church and who was about my age. The woman, who was a hairdresser, said she’d met a man who looked just like me. He was working at a barbershop not far from her home. She’d gotten his number. He must have thought she was flirting. I called the number. The man turned out to be my brother Stephen, the eldest of my father’s five sons.

I didn’t know how I felt when I heard Stephen’s voice on the other end of the line. He asked about my side of the family and gave me my father’s phone number. I’m not quite sure why I called. I wasn’t particularly curious about my father. It didn’t matter much to me what he looked like. I never thought about the life he might have made for himself or why he wasn’t around. This is also what separation does. My grandmother raised me. I hadn’t experienced my father’s absence as a loss. But I mustered up enough curiosity to make the call. By the next week, I was in a car riding shotgun with Janice on our way to his home.

The drive felt long. I didn’t understand the west side of my own city. I’d lived with my brother for a few months in the very same neighborhood, but that was years before. Nothing felt familiar. I don’t remember much of what I was thinking, but I do remember I was nervous and felt somehow guilty for feeling that way. Perhaps I had some distant sense of obligation. I had a family of my own, and there was something that told me I should meet this man whose voice I couldn’t remember.

We pulled up to a large, white frame house not far from the Austin neighborhood where, years later, I would do some of the research for this book. Two of his boys, my brothers whom I had not met, sat out front. Inside, I met my sister, whom I vaguely remembered. And my stepmother had a kind face. She was warm.

Janice and I had been together for three years. I was so glad she’d come with me. We took a seat on the couch, making small talk with my stepmother as I waited for a man I had never seen. I wasn’t sure what to expect.

He wore overalls, or maybe jeans. (This memory seems so long ago.) And he seemed big, but not fat and not particularly tall—maybe five eleven. He was bald and was about my complexion. I don’t remember whether or not he had facial hair. I was lanky then, six two, maybe a hundred and ninety pounds, and still growing into a man’s body. But it was clear to me, as it was to Janice, that this man was my father.

We did not shake hands at first or hug. I can’t remember what pleasantries were exchanged. I mostly watched him watch me for what felt like quite a while. Then, as I do with my youngest son now, who at fourteen is already six one, he moved toward me quickly, put his hands on my shoulders, and spun me around. He seemed to smile, watching me twirl in front of him. Was this pride? I had been to college but had not yet finished. I had a job, was about to be married, and had children of my own. He directed me outside, where we walked and talked in what I remember to be an open field. And I remember it was sunny, maybe spring. And while I still can’t remember what his voice sounded like, I remember what he said.

“Man, I’m sorry for all that shit,” he told me, referring to the group homes and the poverty and the experiences he might never understand. Some things are best left unspoken. I didn’t say much at all. I don’t typically talk much around people I don’t know. But I learned a lot that day. He had just gotten out of prison, again. By then he had done twenty years off and on, earning the title “Big Soul,” a retired member of the Black Souls street gang. He said that he’d had no idea that we were in foster care or that my grandmother died and that I had been on my own for over a decade. He did know that two of my brothers had done time because he thought at one point he’d done time with Jeremiah. He apologized for mistreating him, saying he was ashamed. Something about Jeremiah acting soft and my father pretending not to know him. “I didn’t stick up for him,” he said.

I was angry now, which I wasn’t before. Janice says I looked like I was standing over him, my chest out. I wanted to ask him, What did my brother need sticking up for? Did they beat him? Did they rape him? or say something like, The one time you could have done something! But I couldn’t form words. A moment passed. I looked down and moved on, mumbling something like, “It’s cool,” and after my father made some promises I didn’t expect him to keep, Janice and I left.

We lost touch shortly thereafter. I wasn’t emotionally invested enough to pursue him. I’m not sure he wanted to be pursued. But I did call my brother back. His phone was disconnected. I tried to call the barbershop where he worked. A man answered; the owner, I suppose. When I asked for him, he said he no longer worked there. “Your brother is in jail,” he said.

Sixteen years passed before I heard from Stephen again. It was April 5, 2020. My state, like many others, was under a shelter-in-place order due to the COVID-19 pandemic. My stepmother, the one with the kind face, had sent a request to Jeremiah through his Facebook account. My father had died in August, and she was hoping to reach his sons.

Idid not know my father, but his incarceration had a profound effect on my life. I don’t believe that we would have been close had he never gone to prison, but I know my brothers followed him there. I don’t know what his presence might have meant for his boys, but I know that my grandmother raised us alone. This is the afterlife of mass incarceration. It is the separation from the people you care for or have been told you should. And this is family separation, even if others can’t or refuse to see it. Even if you’ve moved on with your life, and even if you didn’t experience it as a loss, and even if, or perhaps especially if, it takes many years to notice the effects.

The people I met lost children, and they lost them for so many reasons: A missed appointment. A social worker came by the house, and the landlord hadn’t exterminated in months. Someone had an addiction. Someone had a gun. Someone had one too many convictions. Someone was in jail too long. Some of this was justified; some of it was harder to explain. In the end, their children were taken, and there was nothing they could do.

The grandmothers lost children, too, in some of the same ways they lost their lovers. Some were buried, and some were buried but still alive, incarcerated for so many years. The fathers and mothers lost friends, even friends they’d known forever, because their loved ones did something wrong or because they were sent away. The children lost their parents. Some of the parents were made to leave. Some were taken away. In the end their families were separated, and their lives would never be the same.

In a supervised society, the prison and the jail and the law frays our closest ties. It pulls our families apart. It did this to Jimmy, and it did it to me, and it does this to millions of families. And while this happens in so many different ways and to so many different kinds of people, once the law gets between families, they are never quite the same.

Excerpted from Reuben Jonathan Miller’s Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration, published by Little, Brown and Company, a division of the Hachette Book Group.