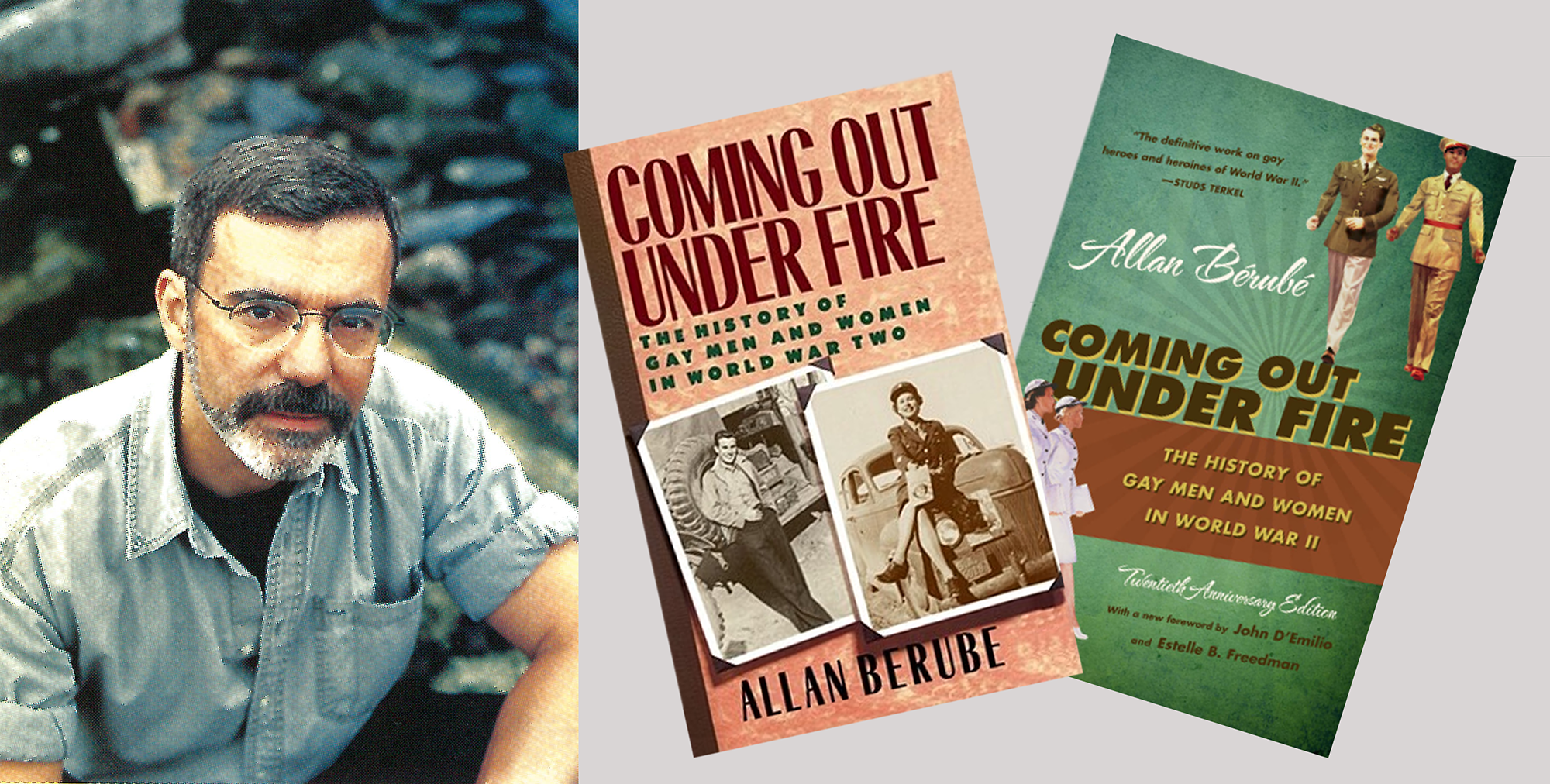

In 2010 the University of North Carolina Press printed a 20th anniversary edition of Allan Bérubéʼs (EXʼ68) book Coming Out Under Fire.

From our archive: Allan Bérubé, EXʼ68, wrote Coming Out Under Fire to tell the history of gay men and lesbian women in World War II. (Photography by Bart Everly)

Allan Bérubé, EXʼ68, died on December 11, 2007.

Taking the step from gay social activist to gay social historian was easy for Allan Bérubé–once he became aware that there was a gay and lesbian history to unearth. Twenty years ago, says Bérubé, EXʼ68, “the assumption was that...you couldnʼt write gay American history, because there were no sources. Everything was covered up or censored or burned or never existed. Invisible, hidden.”

No more. The independent scholarʼs research and writings--most notably his award-winning 1990 book Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (Free Press)--have helped lay the groundwork for gay and lesbian studies. Theyʼve also earned him a MacArthur Fellowship, one of 20 such “genius” grants awarded in 1996.

Bérubé credits the U of C with giving him the skills he needed to read the primary documents so crucial to his research. But he also considers his final year at the University, 1968, one of the main influences on his life and his activism. As an antiwar protestor about to lose his student draft deferment, he started applying for conscientious-objector status and doing draft counseling. Then came the April assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. After the riots that followed, Bérubé and his roommate, Roy Gutmann, ABʼ68, worked with the Quakers to collect food and clothing for the victims. A few weeks later, Gutmann was killed in a racial incident. Bérubé left school and town.

Moving to Boston, he did full-time draft counseling and antiwar organizing with the American Friends Service Committee. Having begun to come out in 1969, he decided to join a “gay liberation collective household.” In 1974 he headed to San Franciscoʼs famed Haight-Ashbury neighborhood and joined another gay commune, this one for craftspeople.

Bérubé snickers a bit when he recalls his hippie days: “People I talk to in their early 20s say, ‘Oh, thatʼs way cool. You were really ʼ70s. Did you have long hair, did you do macramé?ʼ And yes, I did.”

It was Jonathan Katzʼs 1976 book, Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.: A Documentary that led Bérubé to his lifeʼs work. “It made me realize that I could see myself and people like me in history,” he explains simply. Inspired, he read old newspapers, searched used-book stores, and met like-minded people. In 1978 they formed the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project.

“The products of what we did were not articles in scholarly journals,” Bérubé says. “We would do slide shows, public presentations, panels. People would pay to go see it, and thatʼs what funded our work. We were in a continual dialogue with the communities whose histories we were doing.”

Coming Out Under Fire emerged from a box of hundreds of letters exchanged among a circle of gay GIs from Missouri. A friend of a friend found the letters while cleaning out a house and gave them to Bérubé. “I sorted them out and had a good cry,” he says. “It really captured my heart and raised a lot of questions, so I started doing research.”

The book includes information from those and other letters, diaries, about 70 oral-history interviews, and thousands of pages of declassified military documents. Tracing the origins of the militaryʼs antigay policy in World War II, his book was often referred to in 1993 Senate hearings on that policy and was the basis for the documentary film Coming Out Under Fire.

Bérubéʼs current research, on the Marine Cooks & Stewards Union, was inspired by his interviews with WWII veterans who had also belonged to the now-defunct union. This union, which represented the workers who cooked, cleaned, and served on big passenger liners in the Pacific from the 1930s to the 1950s, welcomed gay men and allowed an open culture of “queens.”

With the MacArthur money, Bérubé is buying a video camera to capture his interviews visually as well as orally, hoping to produce a documentary and a book. And, despite teaching since 1990 as adjunct faculty at universities on the West Coast and in New York, his funds grew tight last year, and Bérubé was on the verge of giving up his research work. The fellowship, he says, will allow him to remain independent.

“A lot of lesbian and gay studies now is being done in the academy, for academics, in a jargonistic language that is inaccessible to nonacademics,” Bérubé says. Inaccessible is exactly what he doesnʼt want gay and lesbian history to be.