A classic Chicago hot dog: “History that fits in your hand.” (Photography by Brent Hofacker/Shutterstock.com)

Excerpted from Chicago: From Vision to Metropolis.

The Chicago Hot Dog

Two foods are inextricably linked with Chicago: deep-dish pizza, and the Chicago-style hot dog. In truth, Chicagoans eat many types of pizza, with the absurdly rich native version—as much a casserole as a pizza—as an occasional indulgence. But we are insistent on the superiority of our approach to this most modest of foods.

And for good reason. Unlike the deep-dish gimmick (sorry), the hot dog is Chicago history that fits in your hand. Sausages on bread and mustard come from the Germans; poppy seeds on buns from Eastern European Jews; green-tomato-based relish from the English; tomatoes from “the combination of Jews, Greeks, and Italians living on Maxwell Street, vying for control of the vegetable market”; pickles and onions from all over; sport peppers from Mexico; and celery salt from Lakeview, “one of the major celery-growing areas in America in the 1920s” (now a dense, expensive urban neighborhood). And no ketchup. Because when you have all that—a cross-cultural symphony of flavors combined into the most modest of American foods—what more do you need?

But the heart of the Chicago hot dog is the all-beef sausage, itself a synthesis of Chicago’s earthy foundations and greatest global-city aspirations: the meeting of the stockyards and the White City. Among the many legacies of the 1893 World’s Fair were sausages sold by two Austrian immigrants, Emil Reichel and Sam Ladany. The two men called their company Vienna Beef, and according to the company today, it still hews to its founders’ recipe. And Vienna Beef is everywhere in the city, often marked by the company’s garish red-yellow-blue logo on restaurant signs or umbrellas, from the great (the 72-year-old suburban stand Gene & Jude’s) and the good (the beloved local chain Portillo’s) to the convenient (7-11), distinguished by how it’s cooked and which ingredients are piled on.

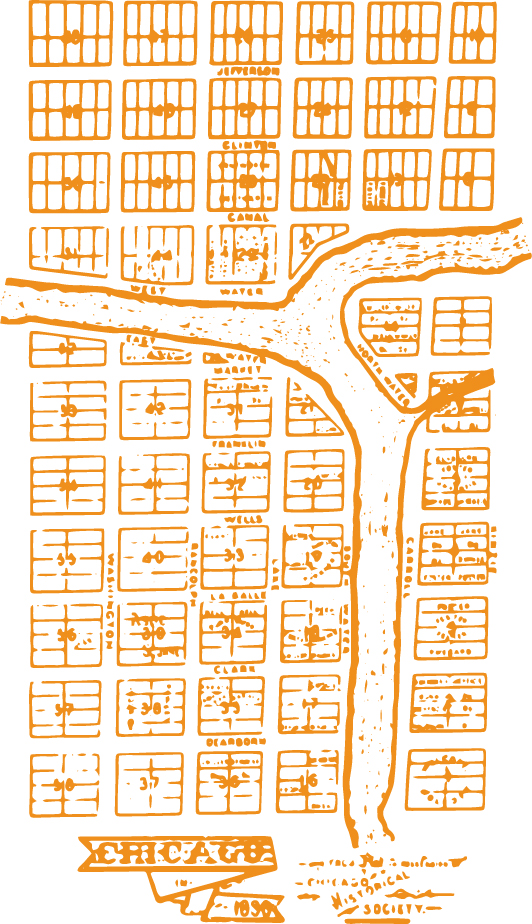

The Grid

Befitting a city that engineered its way to greatness, Chicago is a physically rational metropolis: a remarkably consistent street grid with few exceptions across its length and breadth. The Loop intersection of State Street and Madison Street, long called (with typical Chicago bluster) the busiest street corner in the world, is the zero point; the street numbers go out in the four cardinal directions at eight blocks to a mile. Walking, driving, or biking anywhere is as simple as knowing the coordinates. Chicago’s grid also includes alleys, the most by mileage of any city in the country. This makes the city less dense than New York and it also means garbage bags aren’t left on the sidewalk, and while the prevalence of alley-facing garages encourages a car-dependent city, on summer nights many serve for socialization, like detached, open-air dens inviting neighbors to stop by.

And while Chicago also has a great legacy of urban planning, its grid was laid out for convenience by a downstate man named James Thompson, “one of the great surveyors of the early days,” who “surveyed the islands of the Mississippi River, from the mouth of the Missouri to the mouth of the Ohio.” Thompson’s streets were 66 feet wide, the length of a surveyor’s chain, which remains the standard width, and for better or worse makes Chicago harder to jaywalk in than New York.

As well as his design worked out for its residents and despite coming to define the city, even extending to some of its suburbs, Thompson’s grid was initially for virtually no one. In 1908 the Chicago settler Edwin Gale told the Chicago Historical Society that when Thompson plotted the future city, only seven families lived outside the walls of Fort Dearborn. It was gridded at the behest of the commissioners of the not-yet-existent Illinois and Michigan Canal in order to sell the lots, to finance the canal, to give the grid reason to become a city.

The Bungalow

Chicago can lay no exclusive claim to the bungalow—the term itself is anglicized from a Hindi word meaning basically “Bengali-style house.” The British borrowed the style as well, and it spread throughout the U.S. in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It’s an adaptable idea: a low-slung, one- or one-and-a-half-story house with a hipped roof and an open, relatively informal floor plan and a porch in the front. It is a modest type of housing, which is why the term is often associated with vacation homes.

When Chicago’s population exploded, tripling in size from 1890 to 1930 by adding over two million residents, builders adapted a substantial version to house the city’s growing middle class. “Sociologically, [a] bungalow used to signify a specific kind of homeowner,” the executive director of the Historic Chicago Bungalow Association told WBEZ in 2014—skilled craftsmen, government employees, public-safety workers. Emerging out of the Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized the aesthetics of simplicity, the Chicago bungalow is muscular but pleasant. Brick construction and the stable, low-pitched roof give it a physical and visual stoutness, but the steps ascending to the raised first floor and the central dormer window to the attic give it verticality, and the front windows that run across the first floor—sometimes extended out from the rectangle of the house as a pentagonal pudge and often including stained glass—bring in necessary light. According to the association, there are 80,000 bungalows in the city, about a third of all single-family houses, so many that they encircle the city along its edges, creating what’s known as the Bungalow Belt.

In many ways the success of the bungalow in Chicago is due to a confluence of craft and mass production: the William A. Radford Company, based in the Olmsted-designed suburb of Riverside, helped start the bungalow craze by selling handsomely designed mail-order blueprints that could be given to contractors, often immigrant European craftsmen, to build. The result was that rare thing: quantity and quality, and an architectural style that is beloved despite its omnipresence in much of the city.

Read “The Known City,” an interview with author Whet Moser, AB’04.

Reprinted with permission from Chicago: From Vision to Metropolis by Whet Moser, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. © 2019 by Whet Moser. All rights reserved.