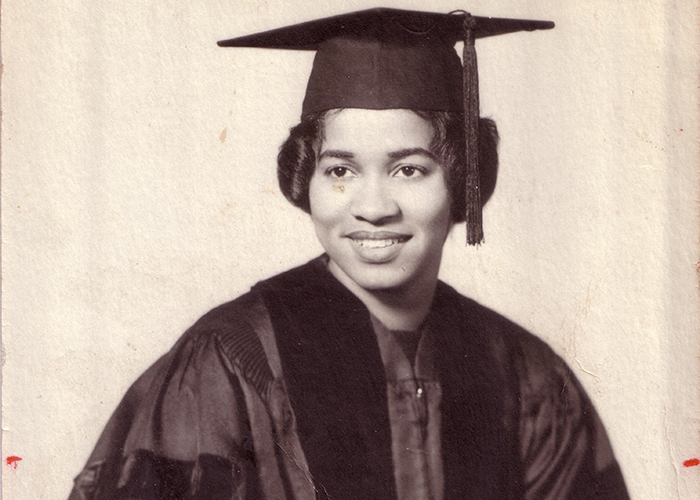

(All photos courtesy Reatha Clark King)

Reatha Clark King, SM’60, PhD’63, was one of the less hidden figures in the space race.

In the 1960s, the race to get a man on the moon was all consuming. While there was never a doubt that the astronaut would be a white man, points out Reatha Clark King, behind the scenes scientists “were so focused on that mission, they didn’t care whose brains helped—black women, white, whoever. If you had the brains, they would find you.”

“You saw that movie Hidden Figures?” says King, SM’60, PhD’63. “There were a lot of hidden figures back then.”

King was slightly less hidden. Her invention of a coiled tube that allowed fuel to cool instead of exploding was a crucial advance in the space race, and she is the lead author of a 1967 paper, “Constant Pressure Flame Calorimetry with Fluorine II. The Heat of Formation of Oxygen Difluoride,” written while she worked for the National Bureau of Standards, now known as the National Institute of Standards and Technology. At the time, oxygen difluoride was being considered as a key component of rocket fuel and has since become a standard ingredient.

Early in her life and career, King faced many of the same obstacles as the African American women scientists depicted in Hidden Figures. But she had factors working in her favor—a crucial one being her University of Chicago degree.

At the time she finished her PhD, societal doubt “because of your race and gender was very strong.” But her degree helped ease those doubts and “soften the hearts of those who would close doors,” she says.

“The world accepted the University of Chicago as second to none,” she says, borrowing a phrase often associated with her undergraduate alma mater, now Clark Atlanta University. Attending these two institutions back to back, King says, helped shape her life goal “to aim to be second to none in all of my endeavors.” She adds, “For me to have that experience caused others to doubt me less than they would have otherwise.”

King appreciates her success all the more because of the way she earned it. By 1954, the year the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools were illegal, she had already graduated high school. She and other sharecroppers’ children in her hometown of Moultrie, Georgia, had gone to grammar school at the local Baptist church, where they were encouraged to get an education, she says, “so we could work out of the hot sun.”

During Black History Week, her class had learned about African American role models, including George Washington Carver. If they studied hard, their teacher said, they could be like him.

Despite those early lessons, King planned to major in home economics at Clark Atlanta and then return to Moultrie to teach at the local high school. After all, George Washington Carver was a man, and in those days, she says, “there were certain fields of study that were appropriate for girls.” To fulfill her major requirements, she needed to take a year of chemistry—where she fell in love with the laboratory work. When the chair of the chemistry department told her she could be successful in the field, she thought back to George Washington Carver and decided to become a research chemist. The chair told her she would need to go to grad school.

King attended UChicago on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, which at the time supported graduate students pursuing doctoral degrees. “You cannot imagine what a confidence builder this is for us country boys and girls in the rural South,” she says, “to have champions like [the fellowship foundation].”

She was interested in physical chemistry, specifically calorimetry: the study of the changes in energy in a system based on heat transfer. (She was also learning about heat—or lack thereof—during the Chicago winters. In her first letter home, she asked her mother to send long underwear.) King worked under O. J. Kleppa at the University’s Institute for the Study of Metals, now known as the James Franck Institute.

In addition to the course work and the cold, King had to adjust to what she calls “the gap between what you’re experiencing and your family back home.” King says she gets her intelligence from her father, Willie B. Clark, who designed his own tools for farm work. His friends called him “Preacher,” both for his religious faith and his intellect, his ability to “figure anything out.” But growing up in the early 20th-century South as one of 13 children, Willie Clark never learned to read and thus had few opportunities.

While at UChicago, she met N. Judge King Jr., a Morehouse College alumnus who was teaching science at Englewood High School (and also driving a cab). After they married, she took the National Bureau of Standards job when he went to Washington, DC, to get his doctorate in organic chemistry at Howard. Among her many assignments was a project for the Advanced Research Projects Agency, now known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (commonly known as DARPA), to find a material that could effectively work as a container for the extremely corrosive compound oxygen difluoride.

She learned that oxygen difluoride ignites in an atmosphere of hydrogen. “I only had one explosion,” she says, adding that at least it was contained under a hood.

King balanced her job with raising two sons, but when her husband became chair of the chemistry department at Nassau Community College on Long Island, New York, her career at National Bureau of Standards came to an end. She became an assistant professor of chemistry at City University of New York’s newly established York College in Queens and found that at a new institution, “if you’re willing to work hard, you can move up the ranks pretty fast.”

She ultimately became associate dean for the Division of Natural Science and Mathematics and then associate dean for academic affairs. Along the way she spent a sabbatical year earning an MBA at Columbia University. In 1977 she became president of Metropolitan State University in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Eleven years later, General Mills tapped her to direct its foundation.

“As a university president,” King says, “you become very familiar with the range of resources needed to lead your organization.”

Much of her work at General Mills drew on her experience in higher education—but from the opposite side of the grant. One area that didn’t, which she found especially rewarding, was disaster relief assistance. Corporate foundations excel at it, she says, “because they can move quickly.”

King retired from General Mills in 2002. Today, along with her involvement in other organizations, she is an emeritus trustee at UChicago and serves on the board of overseers of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award. She’s thinking about writing her autobiography and is taking writing classes.

“I’m a lifelong learner,” she says, “and I don’t apologize for that. Frankly, I think it is one of the wonderful habits I learned at the University of Chicago.”

Updated 05.24.2018 to correct master’s degree to SM.