(Photography by Nathan Keay)

A new book looks at the history of Chicago through the lens of print.

Is it a truth universally acknowledged, that a home in possession of a coffee table, must be in want of a coffee-table book? If so, here’s one for literary-minded Chicagoans near and far to marvel at—not just the object, which is beautiful, but the feat of selection behind it.

Chicago by the Book: 101 Publications that Shaped the City and Its Image (2018) was published by the University of Chicago Press and curated by Chicago’s Caxton Club. The society of bibliophiles, dating back to 1895, publishes occasionally on the book arts and mounts exhibitions with partner institutions in the city.

In the book’s introduction, “Listing Chicago,” Neil Harris reveals the negotiations he and seven fellow Caxton Club members performed to narrow nearly two centuries of a major metropolis’s written record to this relatively trim canon. Harris, the Preston and Sterling Morton Professor Emeritus of History, clearly relished a process that felt impossible and that succeeded, in the end, through sacrifice.

The committee’s working list topped out somewhere between 200 and 300 items. “In good democratic fashion, we voted on all of them in several marathon sessions,” Harris writes. “While many quickly bit the dust, others attracted strenuous and ingenious defenses. … Our textual rejections include dozens of titles that could easily have been part of our book.”

Among the fallen candidates were Edna Ferber’s So Big (more focused on the suburbs than the city; Doubleday, Page & Co., 1924) and Thomas W. Goodspeed’s A History of the University of Chicago (more interesting to scholars than the general reading public; University of Chicago Press, 1916).

That hardly means the University gets neglected. “We decided early on that the creation of the University of Chicago was an event worth recognizing,” Harris notes, and the team recognized it with a breadth of texts—including many by UChicago faculty, such as Robert Maynard Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler’s Great Books of the Western World (W. Benton, 1952), and by alumni, like Sara Paretsky’s (AM’69, MBA’77, PhD’77) novel Brush Back (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2015).

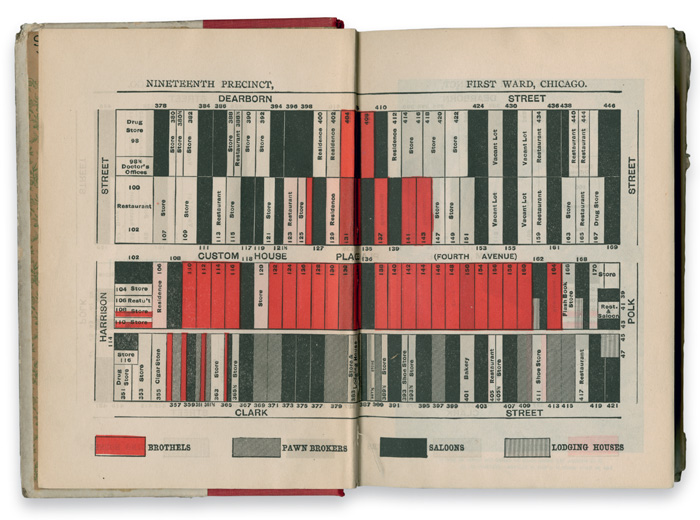

Other faculty and alumni contributed reflections on some of the 101 books’ influence. There’s Divinity School professor emeritus Martin E. Marty, PhD’56, on British journalist and Christian activist William T. Stead’s If Christ Came to Chicago! A Plea for the Union of All Who Love in the Service of All Who Suffer (Laird & Lee, 1894). Following a visit to the World’s Columbian Exposition, Stead mapped the city’s brothels and saloons (see below), scolded the city’s leaders for overseeing such iniquity, and called for a multidenominational Church of Chicago. Committee on Social Thought professor and poet Rosanna Warren weighs the poetic virtues and shortcomings of Carl Sandburg’s Chicago Poems (H. Holt & Co., 1916). And Paretsky pays tribute to A Street in Bronzeville (Harper & Brothers, 1945), the first collection of poems published by Gwendolyn Brooks.

Additional alumni and faculty essayists include sociology professor Andrew Abbott, AM’75, PhD’82; Daniel Bluestone, PhD’84; history professor and dean of the College John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75; history professor emerita Kathleen Neils Conzen; geography professor Michael P. Conzen; Perry R. Duis, AM’66, PhD’75; Paul F. Gehl, AM’72, PhD’76; history professor Adam Green, AB’85; the late Paul M. Green, AM’66, PhD’75; Ron Grossman, AB’59, PhD’65; Edward C. Hirschland, MBA’78; Ann Durkin Keating, AM’79, PhD’84; Paul Kruty, AB’74; Victoria Lautman, LAB’73; Lester Munson, JD’67; trustee emeritus Kenneth Nebenzahl; Toni Preckwinkle, AB’69, MAT’77; Carlo Rotella, LAB’82; English associate professor Eric Slauter; Steve Tomashefsky, JD’85; Michael P. Wakeford, PhD’14; and Lynn Martin Windsor, LAB’47, AB’52. Others are cited in the captions following.

The 101 publications ultimately chosen to represent Chicago encompass books and much more. Novels, autobiographies, scholarly books, and city guides are here, but also pamphlets, sheet music, and magazines. Each selection is photographed and accompanied by an essay on its significance. As a one-volume history of a place most Maroons have called home and many still do, it’s surprisingly exhaustive and more than occasionally surprising.

Here we share seven of the publications through which, in the estimation of Harris and his colleagues, the University of Chicago had a hand—and a pen—in shaping the history of its home city.

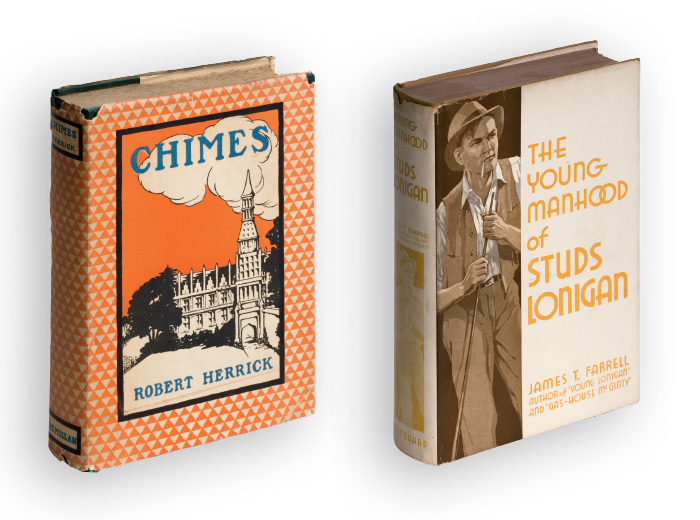

Chimes

A roman à clef about the University of Chicago? You might think of Saul Bellow’s (EX’39) Ravelstein (Viking, 2000) but almost surely not of Robert Herrick’s Chimes (Macmillan Co., 1926). Hanna Holborn Gray finds the 93-year-old novel of campus life during William Rainey Harper’s presidency “not even thinly disguised.” It is “a much better novel than its reputation—or lack of one—would suggest,” she writes. Kind to the University, however, it is not. Herrick taught English at UChicago from 1893 to 1923, publishing his novel three years later. The sharpness of his portrayal, former University president and professor emeritus of history Gray suggests, is closely tied to Herrick’s nostalgia “for the coherence and ethical certainties” he associated with the East Coast, where he was born and educated. To her, he seems to have seen the University through the lens of industrial, striving, materialistic, ethically loose Chicago itself. “Herrick’s Chicago was uneasy with elite institutions, and Herrick was basically elitist in outlook,” she observes.

Studs Lonigan: A Trilogy

Novelist and historian Bruce Hatton Boyer traces James T. Farrell’s (EX’29) South Side–set novels back to Huckleberry Finn and forward to the oral histories of Farrell’s fellow UChicago alumnus Studs Terkel, PhB’32, JD’34. But Studs Lonigan, Boyer allows, has none of Huck’s sympathetic qualities. As readers we “watch with equal measures of enjoyment and dread as the triumphant street fighter in Young Lonigan [Vanguard Press, 1932] gives way to the lost man in The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan [Vanguard, 1934] until finally becoming the bitter alcoholic of Judgment Day [Vanguard, 1935].” At the University Farrell drank in the social sciences and the perspective they gave on his hard-edged experiences growing up in the city. Chicago itself, Boyer suggests, is a crucial character in the novels—“the bars, pool halls, and coffee shops; the grim grayness of the South Side; the oppression of religious beliefs; the street corners, fights, and drunken brawls; the gangs and early deaths; the brothels and venereal disease; the dismal reality of the Great Depression.”

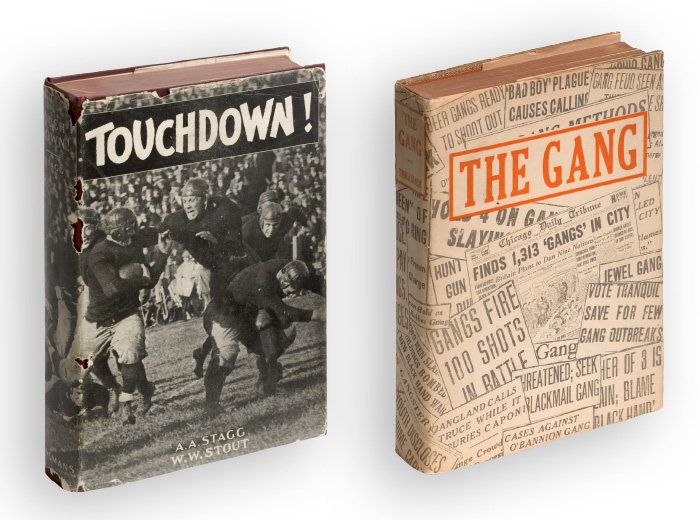

Touchdown!

In Amos Alonzo Stagg’s memoir, the already legendary coach of Chicago Maroons varsity football—not to mention track, baseball, and basketball—didn’t shy from any chance to “criticize the very excesses that he himself had pioneered in college football,” according to historian and Stagg biographer Robin Lester, MAT’66, PhD’74. Those excesses included “the use of teams as advertising and fundraising arms of the institutions, runaway salaries for winning coaches, rampant recruiting of players who were academically unqualified,” and more. Though, by the book’s publication in 1927, his last winning football season was behind him, Stagg remained the first celebrity coach of a sports-obsessed American century, and his account, told to and written by journalist Wesley Winans Stout, performed accordingly. Part football history, part hagiography, Touchdown! (Longmans, Green & Co.) strikes Lester as the book of an icon who “sensed his sun was setting.” In 1932 Robert Maynard Hutchins declined to renew Stagg’s contract.

The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago

Before Sudhir Venkatesh, AM’92, PhD’97 (Gang Leader for a Day; Penguin, 2008), and James F. Short Jr., AM’49, PhD’51 (the Youth Street Project; see Deaths), there was Frederic Thrasher, AM 1918, PhD’26. Attending the University as a graduate student during the heyday of the Chicago school of sociology, Thrasher wrote his master’s thesis on how the Boy Scouts served as a way to keep boys from joining street gangs. His dissertation delivered “a deep sociological analysis of the gang as a unique social form,” writes Northwestern sociologist Andrew V. Papachristos, AM’00, PhD’07. At the heart of Thrasher’s contribution was a recognition of how gangs fit into the larger social order they inhabited: they “occupied an interstitial position in the city, both spatially and socially.” Thrasher’s book, Papachristos emphasizes, continues to inform and energize scholars of this social form 90 years later.

Black Metropolis

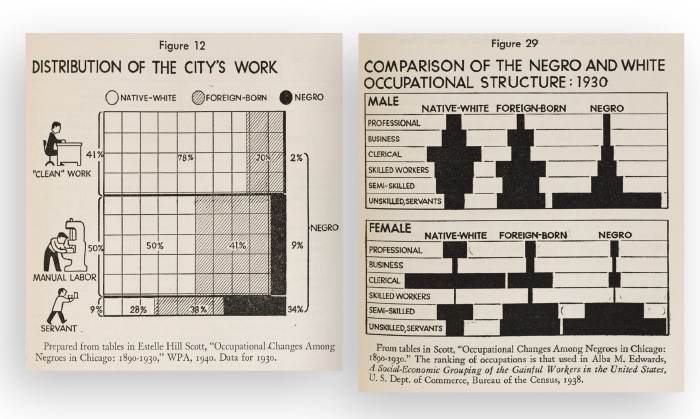

By the mid-20th century, writes former UChicago faculty member William Julius Wilson, the Chicago school of urban sociology “had popularized the view that immigrant slums and the social problems that characterized them were temporary conditions in a cycle of inevitable progress.” That school of thinking expected the same to occur in African American neighborhoods. But this expectation got “a fundamental revision” with the publication of Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1945) by St. Clair Drake, PhD’54, and Horace R. Cayton, EX’33. The African American sociologists examined Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood and found, in contrast to the Chicago school, a stubborn color line “that effectively blocked occupational, residential, and social mobility” for the neighborhood’s minority residents. Their study, which included the charts shown here, remains in print and is frequently cited by urban scholars.

Atoms in the Family

Special Collections director and University archivist Daniel Meyer, AM’75, PhD’94, writes that Laura Fermi was approached by the University of Chicago Press with an invitation to write a biography of her married life, with the ambition to “broaden public understanding of nuclear scientists and their work.” Laura, who was born in Rome and lived there until 1938, wasn’t sure of her English. She agreed, but found that “the actual writing was painful,” Meyer quotes from her papers in the Special Collections Research Center. “I sat at the largest desk in our home with the dictionary on one side and Fowler’s Dictionary of [Modern] English Usage on the other.” The result of her labors was Atoms in the Family: My Life with Enrico Fermi. Shortly before its October 1954 publication date, Enrico Fermi was diagnosed with cancer; he died that November, only 53 years old. Laura, who lived until 1977, went on to publish five more books in English, including Mussolini (University of Chicago Press, 1961) and The Story of Atomic Energy (Random House, 1961).

Days and Nights at the Second City

“The evolution of the Second City,” writes Kelly Leonard, “is a journey through the cultural zeitgeist of a city and a nation.” Bernard Sahlins, AB’43, launched that journey in 1959 when he cofounded a modest cabaret theater with Paul Sills, AB’51, and Howard Alk. In the beginning they were joined by UChicago alumni Ed Asner, EX’48, and Mike Nichols, EX’53, along with Nichols’s frequent partner in comedy, Elaine May. A later generation of Second City performers are better known from their careers in TV sketch comedy: John Belushi, Bill Murray, Gilda Radner, Harold Ramis. These names and more show up in Sahlins’s 2001 memoir, Days and Nights at the Second City: A Memoir, with Notes on Staging Review Theatre (Ivan R. Dee). Included is a kind of primer for review comedy aspirants—what Leonard, Second City’s director of insights and implied improvisation, calls “a template for what is funny and what is true.”