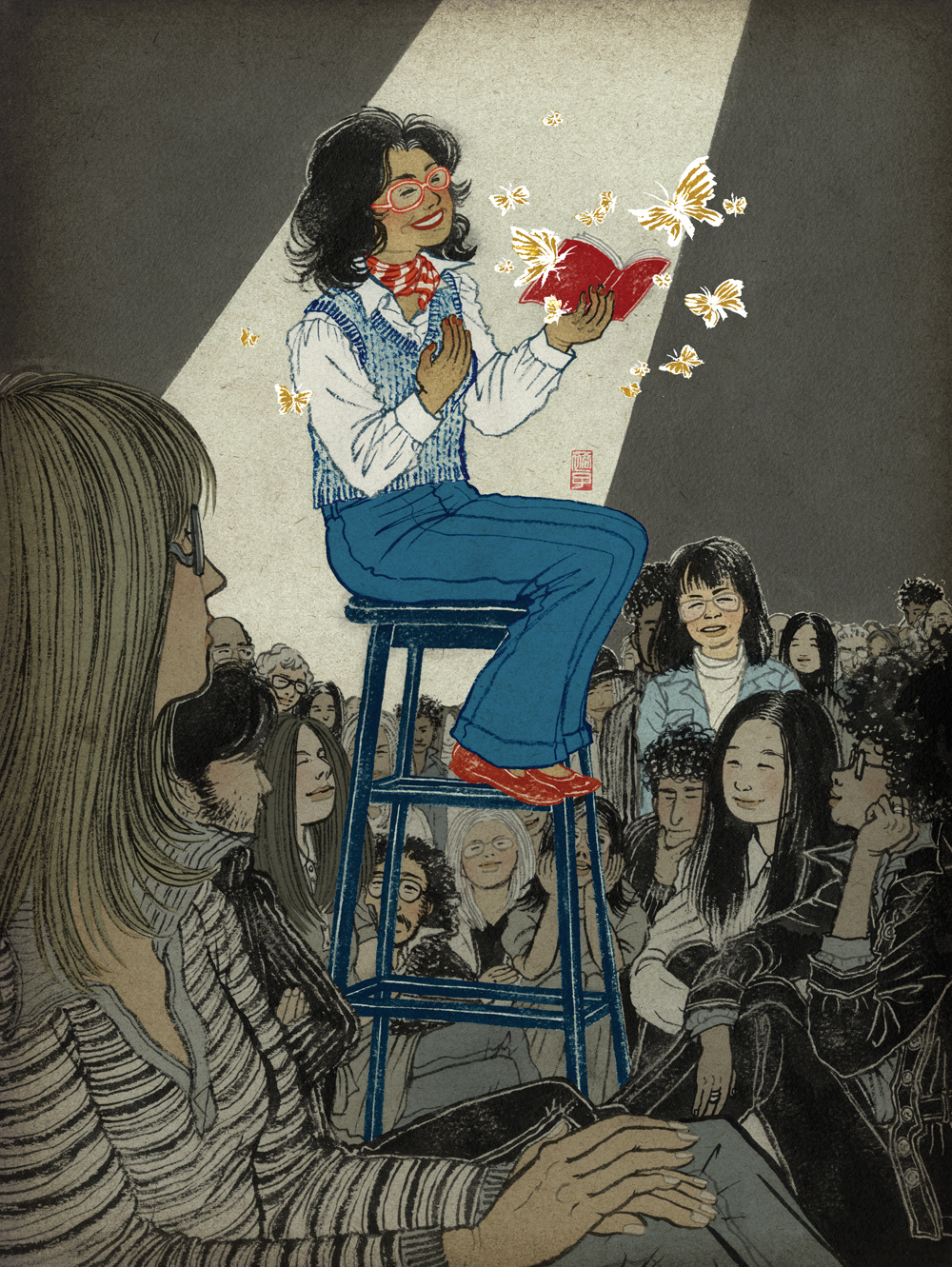

(Illustrations by Yuko Shimizu; photo courtesy the Yasutake family collection)

Mitsuye Yamada, AM’53, transformed her family’s internment experience into poetry.

For years, Mitsuye Yamada, AM’53, never spoke of the 18 months she spent interned in the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho during the Second World War. Yamada was 19 when she, her mother, and her three siblings were forced to leave their Seattle home with no certainty about when they might return.

They were among the roughly 120,000 West Coast Japanese Americans ordered by the US government to remote facilities in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming. Yamada’s father, Jack Yasutake, who had worked as a translator for the US Immigration and Naturalization Service for more than 20 years, was sent to a prisoner of war camp in New Mexico under suspicion of spying for the Japanese. The Federal Bureau of Investigation never found any evidence to support the charge, and in 1944 Yasutake was transferred from the POW camp to an internment camp in Crystal City, Texas.

“It was just something that we never talked about,” reflects Yamada, now 93 and living in Irvine, California. Only in 1962, after her 11-year-old daughter saw a news report about Japanese internment camps, did Yamada reveal to her children that she had been held in one.

Fourteen years later, Yamada broke her silence on a wider scale in Camp Notes and Other Poems (Shameless Hussy Press, 1976), a book inspired in part by her internment. The collection, hailed as “vivid, pain-filled, weighted with irony” by the Los Angeles Times, launched Yamada’s career as an award-winning writer of poetry and essays.

In comments condensed and edited below, Yamada looks back on her childhood, her career as a writer, and the lasting legacy of internment.

My father was a poet. He wrote a form of 17-syllable Japanese poem called the senryu, which is somewhat like the haiku. But haiku are much more ethereal and much more abstract. Senryu talk about everyday problems.

Many of his fellow poets were immigrant men. They would gather in our dining room to write about their daily problems with their wives and their jobs and so forth. Which they had many of.

I remember sitting with them in the dining room as a young girl. My mother was making refreshments—sushi and tea and so forth—and I was serving the poets.

My Japanese wasn’t fully developed during those days, so I didn’t understand everything they were saying, but I was totally enthralled by the process of writing poems. They would take an hour to talk about what had happened since the last meeting and then go into their corners and write poetry. Then they would come back as a group and recite their poems to each other. It was a magical moment for me to sit there and listen to the music of the poetry that they were reciting aloud.

They would tack a large piece of paper, kind of like butcher paper, to the wall. And a calligrapher would write the poem in black ink, very fluid, with beautiful lines, in Japanese.

The process was artistic, as well as musical in many senses. And I grew up with that. It was just something that seemed wonderful to me.

But I didn’t actually start writing until high school. I wrote mostly prose, I remember. Most of my heroines were blue-eyed blondes. I was totally unaware of my ethnic identity at that time. I was trying to blend in with the white majority at my high school.

The outbreak of the Second World War brought sudden changes to Yamada’s family.

My father was arrested by the FBI on December 7, 1941. We didn’t know where he was for a while. He ultimately ended up in a prisoner of war camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico.

This was a real prisoner of war camp, unlike the so-called relocation camps that we were ultimately evacuated to. My mother and brothers and I were so worried about what was happening to my dad. We were not quite sure if he was going to be forced to return to Japan.

Our situation of going into relocation camp seemed like nothing in comparison to what my dad was being accused of—espionage against a country he had spent 20 years working for. It just seemed so unfair at that time. Whatever was happening to us seemed very minor.

At the Minidoka Relocation Center, Yamada worked as a nurse’s aide in the emergency clinic alongside Japanese American doctors who had been forced to close their practices. Keeping busy, she wrote later, was “the trick” to enduring internment: “keep the body busy / be a teacher / be a nurse / be a typist / … / But the mind was not fooled.”

It was one crisis after another in the emergency ward. The doctors, who worked for 16 dollars a month, were wonderful self-sacrificing people. And the head nurse I worked under was a wonderful person. I just admired their work and what they were doing.

In Camp Notes Yamada relates one of the central dilemmas of internment: the “loyalty questionnaire,” which asked interned adults about their hobbies, religion, and languages they spoke—questions designed to determine how Americanized they were. The questionnaire also required them to forswear all allegiance to Japan. Some refused on the grounds that they were American citizens who had never been loyal to Japan. Others, barred by law from becoming American citizens, worried they would be left in stateless limbo if they renounced their Japanese citizenship.

Yamada’s brother Tosh left Camp Minidoka to serve in the US Army. Yamada was permitted to leave in 1943 and enrolled at the University of Cincinnati a year later. She went on to study English literature at New York University and at UChicago.

I had heard from somewhere that a master’s degree from the University of Chicago was the equivalent to a PhD, and I thought, well, that’s for me.

In Chicago, Yamada met her husband, Yoshikazu Yamada, then a PhD student in chemistry at Purdue University. The couple had four children; Yamada didn’t tell any of them about her internment experience until her oldest daughter was 11.

My daughter said, “Why didn’t you tell us?” She couldn’t believe that I hadn’t ever talked about it. And I remember saying, “Well, nobody asked me.” The subject never came up before.

You just bury it inside yourself. It’s an experience that one had to be ashamed of. If it happened to you, it must have been something that you did. I don’t know what the psychology of that is. It was true that I really did bury it very deeply.

Even as a mother of four, Yamada found time to write and edit poetry, though she considered herself a hobbyist, “like a Sunday painter.” One of her projects involved revisiting her journals from Camp Minidoka.

I had been writing all along, sticking bits of paper into a shoebox, like a lot of closet women poets did. I never thought of my camp poems as really being poems. That was why I called them “camp notes,” because they were notes that I kept about my experiences in camp.

When I started to edit, I took out many of the excessive words. I just thought, these words are not central to the poem itself. I remember taking a pen and just crossing out words on the page. I wasn’t really thinking of it as a poem, but as the idea that I was trying to express. I think that explains the starkness of the images in Camp Notes.

In 1976 Yamada met the radical feminist poet Alta Gerrey, founder of Shameless Hussy Press. She convinced Yamada to publish Camp Notes.

Alta invited me to San Francisco to do a reading. We went to various coffeehouses and places like that.

The burgeoning feminist movement in the 1970s, that was quite a revelation to me. And an exciting experience. I had four kids at home and had never really been outside of my little comfort zone. Publishing my book really opened up a whole world that I didn’t know existed.

I met so many wonderful people, including many gay and lesbian poets. The growing consciousness of all of us together at the same time was quite strengthening.

The influence of Yamada’s new friendships is apparent in her later work, including the poem “Masks of Woman”: “This is my daily mask / daughter, sister / wife, mother / poet, teacher / grandmother. / … / Over my mask / is your mask / of me / an Asian woman.” She became particularly interested in collaborating with other Asian American writers.

I met Nellie Wong and Merle Woo at a Women Poets of San Francisco meeting, and we became very good friends. We connected immediately.

And then Nellie and I were featured in a film together, Mitsuye and Nellie: Asian American Poets (1981). It’s a one-hour documentary about Chinese American and Japanese American cultures. That film did very well, I think [Mitsuye and Nellie was broadcast nationally on PBS and featured in several film festivals.]

Yamada continued to write, producing the collection Desert Run: Poems and Stories (Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1988). She also became active in the human rights group Amnesty International and served on its board.

In recent years Yamada has shifted from poetry toward memoir and family history. This year she completed a biography of her father, who died in 1953, only weeks after finally becoming an American citizen.

I remember asking my dad if he felt bitter about his experiences, about the government suspecting him. He said, “No, not at all, because you have to remember the context in that time. You have to remember that during the first few months of World War II after Pearl Harbor, the American country was actually losing, because we were totally unprepared.” He said it seemed kind of natural to suspect a person like him or the Japanese people in general.

My dad did quite well because of his bilingualism. But I often think about how the people who lost the most from the evacuation experience were the first-generation people like my father’s generation.

Most of the Issei [first-generation Japanese immigrants] his age—just imagine, you come to this country when you’re in your 20s and spend 25 years working hard and establishing yourself, buying a house, raising your children, and being quite proud of what you have achieved.

And suddenly, there’s a war, and you lose everything. And you go to camp, and you’re in camp for three or four years, and then the government closes the camp and says OK, now you can go back to where you came from. Well, at that point, most of the Issei had nothing to go back to. There was nothing.

I do think we’re at risk of forgetting some of those lessons. You forget the struggles of the past. Maybe it’s a survival instinct of a sort to forget those kinds of things and to go on with our lives, to look ahead, to keep going.

Poems: Yamada, Mitsuye. Camp Notes and Other Writings. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998. Copyright © 1998 by Mitsuye Yamada. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.