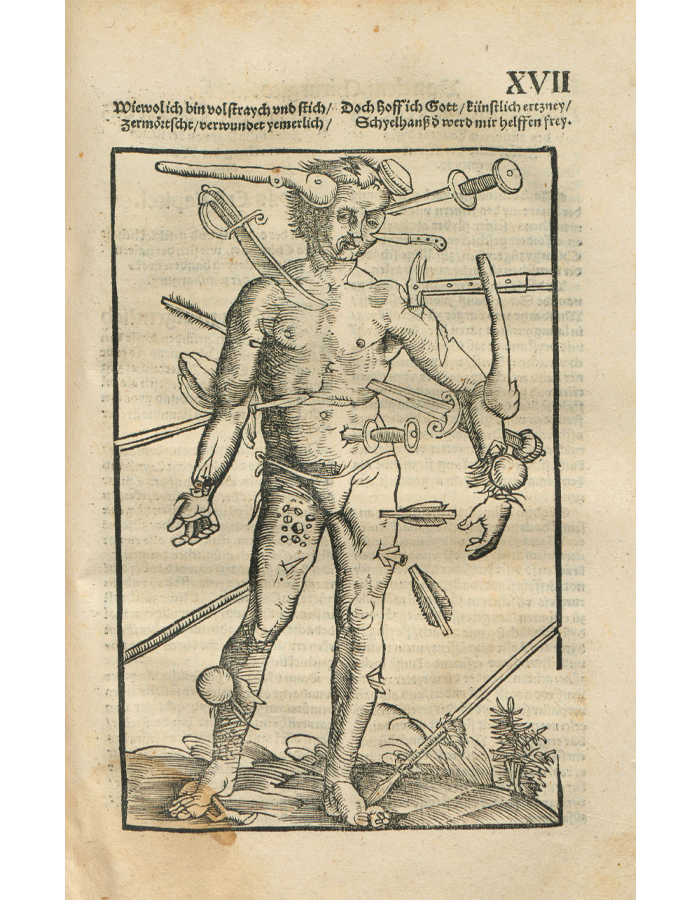

Detail of Wound Man. (Hans von Gersdorff. Wound Man. 1517. Illustration. Feldtbuch der Wundartzney, Augspurg: H. Stayner, 1530. Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

A Special Collections exhibition charts medical history through its imagery.

In 1517 an Alsatian army surgeon, Hans von Gersdorff, created a manual compiling treatments for common field injuries and illnesses: gunshot wounds, loss of limbs, leprosy. Its woodcut illustrations, including this one of a soldier suffering a catalog of war’s ravages, are among the earliest European depictions of surgery.

Wound Man was one of the older images in [Re]Framing Graphic Medicine: Comics and the History of Medicine, a May 9–July 15 exhibition at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center. The term graphic medicine, which emerged 15 years ago, explores the intersection of medicine and comics, and how comics add to the conversation about health care, caregiving, illness, and public health, says associate professor of medicine Brian Callender, AB’97, AM’98, MD’04, who cocurated the show with UChicago Library bibliographer André G. Wenzel.

The collection of serialized prints, illustrated newspapers and magazines, comic books, zines, digital comics, and graphic memoirs examines medicine via imagery. With assistant curators, “Comic Nurse” MK Czerwiec and MD candidate Steven Server, PhD’22, Callender wanted to present a narrative beyond the “great men and their achievements” tradition. Rather, the exhibition offers a history from below, often told by patients themselves.

The show features contemporary comics and graphic novels that concern illness, mental health, end of life, and the representation of doctors and nurses. Callender, who teaches graphic medicine in the College, also selected earlier imagery that critiques the practice of medicine through satire, political commentary, or caricature. The Physician, one of several woodcut illustrations in the exhibition from Hans Holbein’s The Dances of Death, Through the Various Stages of Human Life (London: S. Gosnell, 1803), depicts a clinician challenging—in vain—death personified. “You may have your potions, you may have your empirics,” says Callender, channeling the skeletal harbinger, “but I’ve already come for them.”

Wound Man is one of Callender’s favorite images in medical iconography. “Something that’s often talked about in graphic medicine,” he says, “is this idea of the narrative body, that our bodies tell stories.” What he finds compelling about von Gersdorff’s tragic character is just that—Wound Man is a character. He’s not an anatomical diagram; he expresses emotion, on his face and in his pose. His wounds tell a story.

The curators describe Wound Man as “emblematic of the absurdity of our achievements: the brutality we inflict upon one another and the knowledge and skills to repair the damage.”

“To me,” says Callender, “it’s reflective of the tension that exists within humanity.”