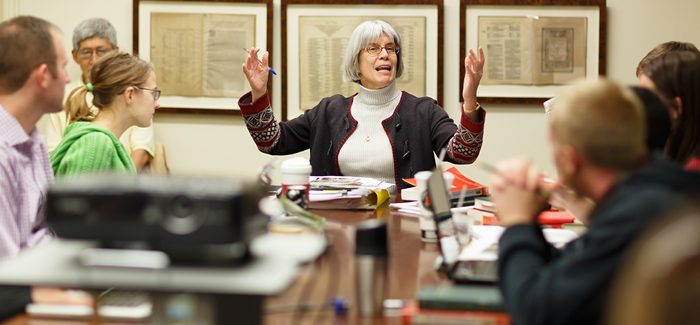

The essence of education, Mitchell says, is a class engaged in “a conversation that’s better than any one of us.” (Photography by Jason Smith)

To approach religion with intellectual rigor, says Divinity School dean Margaret Mitchell, AM’82, PhD’89, is to play with fire. She stokes the embers.

Room 208 in Swift Hall is a corner classroom on the main quadrangle, and on this Wednesday evening about 20 students are loosely convened. They are here to talk about the Gospel of Mark. Some have laptops; some have notebooks. Each has a copy of Novum Testamentum Graece, an original Greek version of the New Testament, and at this point in the quarter every book is roughed up, marked up, looking lived in.

The tall windows are open, welcoming gentle breezes. The sun outside is low and the air is soft. Leafy oak limbs sway and nod. The students await their professor. When she arrives, they will probe, analyze, dissect and discuss, wrangle, read, and talk. For the next three hours or so, they will talk about a couple of chapters in Mark—the passion narrative.

This is a story about talking. And the topic is religion, a subject often avoided in polite company, so easily does it incite displeasure, even animosity, among friends and neighbors—to say nothing of those for whom religion is a fiery and irremediable divide.

It’s about conversations that poke the embers of deep-rooted passions, that probe the personal reserves of faith and belief. About the knotty dialogue between 21st-century scholars and ancient texts, between the truths of antiquity and today’s expressions of fundamentalist fervor. It’s about the scholarly argumentation that takes place in the Divinity School, where the word “rigorous” is more mantra than adjective.

It’s also about the woman who, since she became dean of the Divinity School in 2010, encourages such talk, kindles it, leads and orchestrates it. While Margaret M. Mitchell, AM’82, PhD’89, acknowledges that conducting such talk is volatile, she not only champions the school’s tradition of animated intellectual discourse but says the times call for it.

Religious zeal inflames a spectrum of political movements and policy making, from marriage laws to human reproduction, health care to land use to decisions on war, peace, and the use of violence to further religious aims. From the placement of nativity scenes on public property to the location of a mosque in New York City to the wearing of a burka in a public school. From the revival of evangelical Christianity in America to the rise of fundamentalist Islam in the Middle East.

The proceedings in Room 208 function as might be expected. Students take turns reading the Greek aloud, then translating, then interpreting. It is the interpreting, with Mitchell presiding, that takes the text—and the class discussion—to rich and surprising levels.

The vocabulary and syntax of ancient Greek are more open to ambiguity than English, creating a wider range of meanings. So students venture their interpretations but are pressed to defend their positions. Mark is Mitchell’s critical wheelhouse; she’s a world-renowned scholar on early Christianity. She wields the scalpel—but with a grace that turns the blade to baton, that reveals the Bible as literature.

Mark 14 and 15, she points out, present “an episodic narrative in which time slows down,” moving the reader “in slow motion toward the inexorable action” of Jesus’s final days.

“The text is a Frankenstein,” says Cameron Ferguson, a doctoral student from Minneapolis. What he means is that there are multiple editions of the Gospels and that scholars have sifted through these earliest codices to create what seems to be the best reconstruction possible. But he might as easily have said this diligently assembled “Frankenstein” is a monster of intellectual intricacy. “Mark is a master at using vocabulary, sentences, and ideas, and having them reappear,” Ferguson explains later. “You need to read the text over and over again. He wants it to ping with you.”

Ferguson is expected to give a presentation later in class on the correlations—the “pings”—between Mark and the writings of Paul, and he is anxious about it. “This is Dean Mitchell’s baby,” he explains later. “She knows her stuff, and, if you don’t, she’ll hold you accountable.”

Swift Hall, home to the University of Chicago Divinity School, is a stone fortress on the main quadrangle, bedrock solid and old-school classic. The University’s first president, William Rainey Harper, a Hebrew and biblical scholar, believed any major research university should have the study of religion as a central enterprise. And to this day Swift remains the locus for scholars whose explorations into religion’s influence, history, rituals, texts, and traditions have informed deliberations spanning the globe.

Mitchell, the Shailer Mathews professor of New Testament and early Christian literature, became the school’s 12th dean in July 2010. She has described the school as “a tough-minded, sprawling, lively, engaging, and ongoing conversation about what religion is and why understanding it is so vitally important.”

A self-described “career research scholar and educator,” Mitchell has also called “the cultivation of new knowledge through research” the school’s dominant ethos, saying that “what makes the Divinity School unique is the wide range of traditions, methodologies, dispositions, and commitments that all come together here in a spirit of reasoned, critical debate.” It is important, she insists, to take the intellectual discussions to others, but to do so—to engage religion fully, honestly, and rigorously—is to play with fire.

One problem, the dean explains in her Swift Hall office, is that polls show people are ignorant about religion, even their own. As the subject infuses current events, people can become numb to it—or, if not, they feel skittish about discussing it honestly. “Everybody’s bored by it, they’re frightened of it, paralyzed by it, and they think religion is just intractable. And one reason they think it’s intractable is because it’s those people who think that.”

Another reason religion is difficult to discuss, she says, is that those people’s religious beliefs are seen as “utterly private, ... an opinion, and you can’t talk people in or out of it. It is a preference. You can express it, but you really can’t argue about it.”

This sense that faith is both personal and subjective reinforces “a very simplistic reason versus belief kind of assumption,” she continues, “that religion is about belief, faith, a leap of faith, as in a kind of ‘there’s no evidence for it but you just decide to jump off that diving board,’ whereas everything else in our experience—science, technology, everything else—is somehow reasoned.”

But the word “faith,” the scholar notes, has its roots in the Greek pistis, which can mean a conviction born of proof—a more rational, intellectual understanding of the idea than the contemporary notion that faith is a childlike belief in the unseen or an unquestioning fidelity to custom and creed.

Religion has been on a kind of deathwatch since God was pronounced dead in the early 1880s, most famously by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. A century’s worth of scientific discoveries and technological advancements have dissolved large parcels of the spiritual landscape and relegated supernatural terrain to the precincts of superstition. While God’s obituary may yet remain unwritten, the religious realm often resides as an incongruous partner to our more secular, scientific, and sophisticated modern world. Not irrelevant, but anachronistic. Not exactly in the same category as legend, myth, and folklore, but perhaps an outmoded human invention whose value and power in explaining the universe and regulating society make it an endangered species of human culture.

Even so, religion thrives and is pervasive globally in human affairs—as a force for good and bad—and it’s essential to discuss and understand how it operates in the world. “Some people may see religion today as vestigial or quaint,” says R. Scott Appleby, AM’79, PhD’85, director of the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. “But it continues to play an important role in society, not least as a lightning rod for conflict.”

Rather than nurturing ecumenism, the world’s religious renewal appears to have fostered sectarian divides. Religious convictions run deep, both in individuals and among people united in faith. Challenging another’s belief system—whether through disdain, ignorance, or good intentions—goes to the heart of that person’s self-identity, their sense of morality and propriety, and ultimately their relationship with God. And even attempts to understand (how child abuse could go unpunished in the Catholic Church or terrorism emerge from Muslim faith) expose raw edges and sensitivities when “others” voice their opinions. The hazards of ignition are strung tight.

As conductor of the religious conversation at UChicago, Mitchell steers the Divinity School not so much toward harmony as a common understanding of the enterprise. She does not want the school perceived as “the place where these softheaded, mushy religious people hang out and make each other feel good.” Or as “the place where they indoctrinate you to be religious.” Or “where they indoctrinate you to be against religion, the place where faith goes to die.”

The Divinity School directly engages the larger society through the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion. Operating on the principle that “the best and most innovative scholarship in religion emerges from sustained dialogue with the world outside the academy,” the center encourages an unflinching public conversation.

“People study religion for a lot of different reasons,” Mitchell explains. “But you can’t get by here with either sloppy devotionalism or with knee-jerk ideological opinion masking as argument. Everybody’s got to argue their case.”

Alireza Doostdar, who joined the faculty last year as an assistant professor of Islamic studies and the anthropology of religion, finds in the Divinity School “colleagues genuinely interested in learning about my work and engaging with my arguments, both for the sake of understanding the Islamic contexts I study but also for comparative purposes across other Muslim societies as well as non-Muslim ones.”

Doostdar wrote his dissertation on modern, middle-class Iranians’ fascination with the occult, the paranormal, and the supernatural, and he is now researching mystics, witches, New Age spirituality, and jinn—spirits, according to Muslim legend, capable of taking on human or animal form to exert supernatural influence over humans. Rather than “various intellectual enclaves formed around religious traditions or even disciplinary approaches,” he explains, faculty and students “are encouraged to know more than one tradition, and to cultivate a comparative understanding—on Jewish, Christian, and Islamic mysticism, for example.”

The Swift Hall conversation—whether in a classroom, office, or hallway; or at the weekly Wednesday lunchtime forum; or in the basement coffee shop, Grounds of Being—“unites rigor and respect for persons,” Mitchell says, “but neither is sacrificed for the other.”

In Room 208 those layered, timeworn chapters in Mark provide a wealth of scholarly goods to be opened and shared, plundered and consumed. As students read and speak, Mitchell inquires and nudges and prods. When they ask questions, she sends them after answers, down the lines of text and through the channels of their own brains. Her classroom approach still incorporates the advice she was given as a 21-year-old about to teach prep school students not much younger than she: “Never leave your students with a world that’s finished.”

The class requires a healthy grasp of ancient Greek and a thorough understanding of Jewish and Gentile cultures, the Greek and Roman worlds this budding new religion was infiltrating—because each group would read and respond differently to the text. The teachings would convey different meanings of emperors, messiahs, and a new world order. About the paradoxical kingship of Jesus, not a kingship of coronation but of suffering. About the kingdom of God. And the irony of the son of David riding into the royal city of Jerusalem on a beast of burden and identifying this mysterious rogue with the title Son of Man. “So what do you do with a crucified miracle worker?” posits the dean. And the students leap on it.

On the meaning of anointment. And Jesus as Christ, the anointed one. Is it significant, a student asks, that Jesus is called “the anointed one” before he’s anointed? To which the dean answers: “What do you think?” Leading to a dive into the author’s literary sandwiching techniques—the ping device—in which elements appear and repeat and reappear. Not just in Mark but in older Jewish texts calling for the Messiah, the anointed one, who came, accepting death, in fulfillment of the Scriptures.

“That’s the beauty of a class,” she says. “That’s what I love about teaching. It’s that you can just feel that moment when the tide is rising, when everybody is on their game and everybody contributes to a conversation that’s better than any one of us. That’s what education is about. It’s not just about the sage pontificating and the students writing it down. It’s about inquiry is fantastic.”

Another misconception plagues the societal discussion, Mitchell says: “Religion is not just private,” but the “world’s religious traditions are in many ways themselves media systems ... communicating and doing things in the present world. ... And it’s a crucial matter that we seek to understand what these things—that at least some people think belong under the tent of religion—what are they about and what are they doing.”

Which explains why the scholar says the times call for the conversations emanating from Swift Hall, even when the interplay of ideas and faith, both personal and public, can be inflammatory. “But that’s also why this divinity school has a contribution to make beyond the walls of the Divinity School and the University,” she says. It’s “why we need fireworkers,” people with “specialized skills” who help create “a clearing space where the world’s religions can be discussed apart from dogmatism, apart from bigotry, apart from condescension, apart from apologetics. But, instead, in reasoned argument.

“The need for the work we do couldn’t be greater than it is—and the hunger for it, frankly.” But, she cautions, “I don’t want to go too far with the utilitarian argument. ... I also think a scholar shouldn’t have to justify a project just because it might help the State Department. It ought to be enough to try to figure out this Sufi mystic group.”

The intellectual sparring in Room 208 goes on and Ferguson eventually presents his case, doing fine (despite his trepidation) to demonstrate how the writer we know as “Mark” may have been influenced by the letters of Paul. The grad student later admits that he sometimes wonders if he has “the chops” to earn a doctorate here, says he is working terribly hard, that life in the Divinity School is grueling, that he constantly feels the pressure—and that he loves it. “It’s a stressful utopia, as paradoxical as that sounds.”

It was only a few weeks ago that Ferguson, playing intramural soccer on Stagg Field, fractured his fibula. Staff at the University hospital insisted they apply a cast, but that was at 5:45 and class with the dean was at 6:00. So he argued vigorously with the nurses, got some Vicodin, and hobbled to Swift Hall, up the steps and into 208. The cast could wait. He couldn’t miss class. Mitchell gave him a ride back to the hospital when class was over.

Education, says the dean, for students and faculty, “is about structuring a conversation where people can make their contribution” and creating “a climate where they can trust that they can ask questions and not fear that every question is some revelation of their own ignorance.”

Mitchell, says Chris Hanley, MDiv’13, a pastoral care associate at Lutheran General Hospital, “is eloquent, intellectually rigorous, and curious. And she’s very, very respectful to her students—maybe ‘respectful’ is not strong enough.”

The shadowy, tiled hallway that leads to the dean’s office is lined with large black-and-white portraits of the 11 deans who preceded Margaret Mitchell. All are men, including her predecessor and husband, Richard A. Rosengarten, AM’88, PhD’94, a scholar of religion and literature. Mitchell added her own honoree, hanging a black-and-white photograph of Anne E. Carr, AM’69, PhD’71—striding through the front doors of Swift Hall—on the wall of her office. Carr was a Roman Catholic nun who did groundbreaking research in liberation theology and feminist theology, and who, in 1977, became the first permanent female faculty member in the Divinity School.

Mitchell and her husband are Catholic. They have raised two daughters, and her familial geographic roots extend to New York City; Long Island; and Old Greenwich, Connecticut. The Divinity School’s tradition is that the dean comes out of the faculty, then returns to the faculty when the term is up. Mitchell, who joined the faculty in 1998, is even more acculturated than that, having earned a master’s from Chicago in 1982 and her doctorate in 1989. “She made her mark right away as a student,” says one of her former advisers, the eminent Martin E. Marty, PhD’56, Fairfax M. Cone distinguished service professor emeritus of the history of modern Christianity. “She was a natural leader” who now, he says, “has universal respect as a scholar.” She’s an expert on New Testament and primary Christian texts, the poetics and politics of ancient Christianity, and the evolving relationship between earliest Christianity, Hellenistic Judaism, and the Greco-Roman world.

“In my own study,” she says, “I’m not in quest of God. I’m in quest of a better understanding of ancient Christianity,” focusing on “the origins and early rise of the Christian movement ... to see how a rather extraordinary, revolutionary religious movement began its self-articulation and actually got people to adhere to extraordinary claims about a crucified son of God.” Even Paul, one of the movement’s first, most devout messengers, she says, knew this message was “unthinkable” and “utterly foolish,” yet would claim it as a “divine plan.”

She adds, “One of my big overarching interests is how the early Christians created what for them was a meaningful culture out of various strands of influence.” Her quest, then, requires an understanding of those cultures—because, she says, religions are also “about money and family life and rituals and they are about texts and world views, all these things, which is why studying religion is so fascinating.” And it calls for a thorough probing and study of the earliest documents, how they were understood then and are understood today, by readers of different cultures.

“From a historical point of view,” she says, Christianity’s rise was “an utterly unlikely event, but it is the case that Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire around the year 380,” and became “the cultural transmitter of many of the values and texts of the classical world in both the West and into the East. Now Christianity and its purveyors often claimed that it was distinct from the world that it arose in,” but “you could also argue that it’s deeply rooted in Hellenistic Judaism and it’s deeply rooted in the wider Mediterranean world out of which it emerged.”

She knows those worlds, talks about them ardently, and her analysis is incisive, intense. “She’s very passionate about what she does,” says Kathryn Ray, an MDiv student from Wisconsin who’s also pursuing a master’s in the School of Social Service Administration. “There’s almost a reverence for her subject matter.”

Ferguson says Mitchell is “unbelievably kind” and “really cares for students as if they’re her own children.” But, he adds, “When it comes to scholarship, she will come after you.” He remembers watching her respond to another scholar’s paper on Paul as a Stoic at an academic conference. She “dismantled him,” he recalls. “She methodically took him apart. It was masterful.”

“The University of Chicago,” says Ray, who spent much of this past summer doing human rights work in Nicaragua, “has a reputation—more so in the past—of being cutthroat and competitive.” But she has found its divinity school to be a community of committed scholars and a reflection of the dean—neither “the stereotypical detached scholar” nor “someone who is just complimentary and encouraging,” but a person in whom can be found a melding of strengths. “Dean Mitchell encourages us to think creatively, differently about disparate ideas and to turn new ideas out of old ideas. She challenges us to grow and change and find the truth where we didn’t expect it. A lot of students are intimidated by her,” Ray says, “but she invites students to her house, and she is the most gracious host. She’s a warm and welcoming person.”

And just as erudite, complex, and engaging as the Swift Hall conversations she orchestrates.

Kerry Temple is the editor of Notre Dame Magazine.