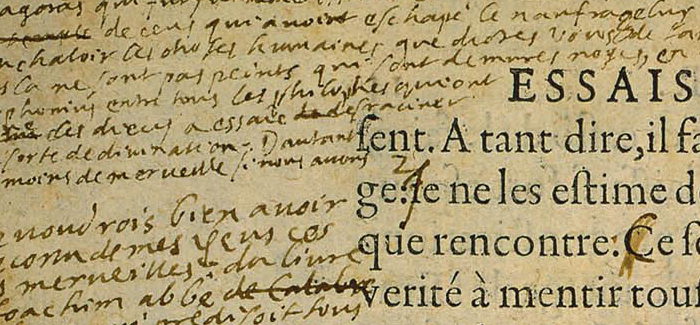

A close-up of an annotated page from the Bordeaux copy of Montaigne’s Essais. See below for a full view of the page. (Photo courtesy Montaigne Studies)

In a European Civilization course at the Center in Paris, Philippe Desan deciphers layers of meaning.

On a gray October morning in Paris, the students in Philippe Desan’s European Civilization course are trying to make sense of the Essays of Michel de Montaigne.

Montaigne was the first to use the word essai (to try) to describe a piece of writing. But Montaigne’s essays—full of digressions, contradictions, and deeply personal confessions—could not be more different from formulaic five-paragraph persuasive essays, the bane of composition students everywhere. “Stream of consciousness,” is one student’s description of Montaigne. “It’s like reading somebody’s diary,” says a second. A third student is blunter: “He’s all over the place.”

The theme of today’s class is self-fashioning, meaning the process of constructing your own identity and public persona. Of the 19 students in the room, at least half could be mistaken for students from the Université Paris Diderot, across the street from the Paris Center. The women wear minidresses or slim jeans with flats; one man keeps his scarf on throughout class. And while Desan, a native Parisian, has brought along a small china cup of espresso (the center has an espresso machine, bien sûr), several of his students have their own diminutive paper cups too.

On the whiteboard Desan, Howard L. Willett Professor in Romance Languages and Literature, has drawn a timeline of the different versions of the Essays, known as “layers”: the A layer (an edition of 1,000 copies published in Bordeaux in 1580), the B layer (6,000 copies, published in Paris in 1588), and the C layer, essays published by Montaigne’s adopted daughter in 1595, three years after his death. Each layer included more essays than the previous one, and more additions to previous essays. Of the 108 essays Montaigne wrote during his life—“As Montaigne tells you,” says Desan, “he will only stop when there will be no ink in the world, or no blood in his flesh”—the students were assigned four for today’s class, “To the Reader,” “Of Books,” “Of Giving the Lie,” and his final work, “Of Experience.”

Manuscripts from the 16th century are very rare, Desan explains, because once a manuscript had been printed, it was destroyed. But in the 18th century, in a convent near Bordeaux, a copy of the 1588 edition—the B layer—was discovered, which included Montaigne’s handwritten annotations. “It’s called the Bordeaux copy, and it’s a national treasure in France.”

To preserve the faint markings, the book is stored in complete darkness, and “every 30 or 40 years” a scholar is allowed access. “I was lucky to be allowed to see it,” Desan says, almost offhandedly, “and I did for the French government a color edition.” A special camera, which worked in near darkness, was used to create the reproduction. “And that’s what we have here.” He holds up an enormous book bound in blue cloth.

“Small anecdote about that,” he says, in a Montaigne-like digression. Between the pages of the precious book he discovered some hair, “probably from a beard,” Desan says. “I have those in Chicago in a tube and have been looking for somebody in the science department to give me a DNA analysis. It would be neat to maybe clone Montaigne in 20 years or 50 years.” The students laugh incredulously. “Maybe it was from a librarian in the 18th or 19th century. I don’t know,” Desan says, smiling. “But I like to believe that it might be Montaigne.”

The students struggle to pass around the unwieldy book, which weighs more than 13 pounds. Its inner leaf credits “Philippe Desan, Professeur a l’Université de Chicago, Vice-Président de la Société Internationale des Amis des Montaigne.” Desan is one of the world’s foremost experts on Montaigne, but Montaigne himself “is not an expert of anything,” he says. “He’s a typical French intellectual.” Jean-Paul Sartre defined an expert as someone who speaks about what he knows, while an intellectual speaks about what he doesn’t know: “And this is Montaigne.”

“This is why he is different from Machiavelli,” says a woman in a fashionably kitschy sweater. (The group read The Prince the week before.) “Machiavelli is an expert in what he talks about.”

“Exactly,” says Desan.

The discussion turns to the “three privileged others” in Montaigne, that help him define himself. “He calls it ‘three commerces,’” says Desan. “‘Three types of association,’ often it is translated, but the right word is commerce.” These correspond to the various stages of his life: As a young man, friends were the most important commerce. Later, this became women (always plural). “But then Montaigne tells you, with age, you know, it’s a complicated commerce,” Desan says, smiling again. “So what comes last, the last commerce, that pleases you most?”

“Death?” guesses the man in the scarf.

“Death is not a commerce, no.”

“Books,” another man suggests.

“Exactly. Books! ‘Of Books.’ Books is the last commerce, the last part of your life.” In telling the reader why books have taken the place of women, “Montaigne is very crude about this. He tells you precisely how many times he did it in one night. He’s boasting a little bit,” says Desan. “Now he’s 40, 45 years old, he says, I prefer books.” The students laugh.

Through the interaction with the three commerces, “your self is always evolving,” says Desan. “He doesn’t believe in the frozen self. ... As Montaigne tells you, what I say today is different from what I say tomorrow. But that does not mean that what I say tomorrow is better than what I say today.

“I always confuse the two painters,” says Desan, snapping his fingers in irritation. “The one who paints the Cathedral of Rouen.”

“Matisse?” a student volunteers.

“No, not Matisse—”

“Monet,” comes a better guess.

“Monet. I always confuse Monet and Manet.” In the famous series of paintings, Claude Monet captures the cathedral in different light conditions throughout the day. His theory was that there is no one cathedral, just a viewer’s ever-changing impression. In his essays, “that’s what Montaigne is doing. He’s one of the first Impressionists, if you prefer.

“That’s just not the way we’re taught to write at the Little Red Schoolhouse,” says Desan, referring to the nickname for the popular undergraduate course Academic and Professional Writing. “I always have a fight with them,” he says, because “they make you write like lawyers. I write in a French way.” In this style of writing (which owes a bit to the French art of seduction), “you don’t reveal your ammunition right away,” says Desan. “Certainly not in your introduction.”

Syllabus

European Civilization, taught in English, is one of the most popular study abroad programs at the Center in Paris. Its appeal is obvious. The course, which meets every day, compresses a yearlong Core course into 10 weeks. There is no language requirement (unlike the equivalent course taught in French). On Fridays, students go on guided excursions to sites such as the Louvre and Versailles.

Courses are taught by three UChicago faculty members, who each teach one three-week segment, the equivalent of a quarter-long course. This fall, Desan taught the first segment. History professor Paul Cheney, the center’s academic director for 2014–15, taught the second segment, and Arnaud Coulombel, AM’93, PhD’06, outreach coordinator at the center, taught the third.

In addition to a reading packet, the assigned texts in Desan’s segment included The Prince (Penguin) by Niccolò Machiavelli; On Christian Liberty by Martin Luther; Discourse on the Method by René Descartes; Lazarillo de Tormes (Penguin), heretical and therefore anonymous; and History of Western Civilization: A Handbook by William H. McNeill, LAB’34, AB’38, AM’39.