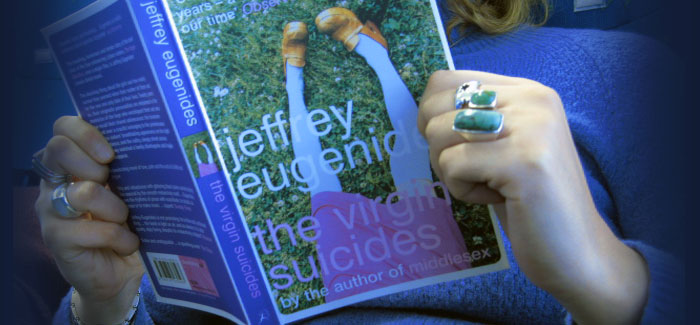

(Photography by giuliaduepuntozero, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Writer Jeffrey Eugenides charms local readers who aren’t afraid of Derrida.

For a few hours in early May, novelist Jeffrey Eugenides basked in Hyde Park’s version of a celebrity welcome. An eager young crowd filled the Logan Center performance hall for his late-afternoon reading. They lined up for the author to autograph their copies of The Marriage Plot, his latest book, and stayed in their comfy orange seats for his Q & A with book critic Donna Seaman. “You’re much better than my students at Princeton who never come out in the afternoons,” said Eugenides, the 2013 Kestnbaum writer in residence. “Don’t put it on Facebook.” Like his fiction, the author was gracious, funny, and expansive—though we abridge the interview here.

DS: Is empathy essential to fiction?

JE: To write about a range of characters, you’re going to have to admit that your own mind and ego are not at the center of the world. Writing can make you into a terrible person that no one wants to live with, but it can make you a listener and attentive to other people’s problems. Interestingly, I’m often accused by my wife of lacking all empathy. I think I try to have it in front of my computer; maybe I’m exhausted and have used it all up by the time I come down to make breakfast. The goal or ideal for me would be a Tolstoyan empathy, where the writer really understands what everyone is feeling, male and female, and what the dog is feeling as well.

DS: You’ve said imagination is not enough—sometimes research is necessary. Talk about that.

JE: I learned about research the hard way. I was writing Middlesex and hadn’t envisioned it would be historical. But I realized that the character had a genetic mutation that I needed to follow back through the parents and grandparents. So suddenly I’m back in 1922 trying to write about Greeks who live in Asia Minor. I thought I could write about their lives through my imagination, because that’s how I’d always worked. But I couldn’t imagine the scenes or the people, so I finally started doing research.

Writing about bipolar disorder in the The Marriage Plot, I also had to acquaint myself with a few facts. You don’t want to overdo the research. I find out a little bit about what the person might be like and then I imagine—what if it was me and I was living with these sets of circumstances? It’s a bit method acting and a bit research, the way I construct characters.

DS: How do you use autobiographical material?

JE: I gave up trying to invent characters out of thin air, which I did for many years as an apprentice writer. I realized I had to base characters on people whom I knew. Maybe three or four people would be put in one character, but it’s not a one-to-one correspondence, ever. Sometimes I’ll use things that have happened to me and mix those with things that have happened to other people. To be honest, when the book is finished, I can’t remember what really happened to me and what I put in the book.

DS: How does Detroit figure in your work?

JE: It’s very strange to grow up in a city that is hemorrhaging population. When I was a kid, Detroit was a metropolis and the fourth biggest city in the country. Then we had the riots in ’67 and the whole city emptied out; buildings started to decay and were demolished. As a kid you think that’s normal. I didn’t realize until years later that the experience of growing up in Detroit put me on close terms with the evanescence of life. That’s really what The Virgin Suicides is about.

DS: You have a Greek and English-Irish heritage—how is that important to you?

JE: I’m half Greek and half hillbilly; that was my inheritance. Both my parents were born in the States, but my father’s parents were Greeks from Asia Minor. When I was little, every Sunday the house would be filled with immigrant Greeks speaking Greek and carrying on all the customs. The men would sit in the living room talking politics and playing backgammon, and the women would be in the kitchen, cooking.

My mother’s side of the family was basically drunk all the time, committing violence, and also singing very well. So I was acquainted with all different parts of America. I draw on that only as I need to. If I come up with a story idea where Greeks would be useful, I’m happy to pilfer the Greeks in my family to make the story work. But I never say, “I am Greek American; I wish to now speak about the Greek American experience.”

In The Marriage Plot, I wanted to paint a portrait of someone, Mitchell Grammaticus, who is Greek like I am. When he goes to Greece all he finds is how American he is; that was my experience as well.

DS: There’s a funny moment where Mitchell is in Greece and feels like he’s seeing his face everywhere.

JE: My friend Adam Thirlwell, the British novelist, went to Greece. He was in a tourist boat that broke down. A fisherman came out to fix it who apparently looked exactly like me. So I had the idea that whole pockets of Greece were populated with me doing other things—making feta cheese, fixing boats. I decided to put that in the book.

DS: Is the novel of ideas alive and well?

JE: Very much so. I don’t think I write them, even though people say or complain that The Marriage Plot is full of big ideas and names that people get scared of. Not at the University of Chicago—no one is scared when you say Derrida here, but vast swaths of the nation are petrified if you say Derrida.

I tremble with happiness to think of Saul Bellow [X’39] being here. He’s one of my favorite writers, and a writer of the novel of ideas. It sounds so heavy and awful, but when you meet a real novel of ideas, there’s nothing more exciting. You feel like it’s teaching you about life and how to live—not in a way that’s like taking castor oil, but the opposite. More like ice cream.

DS: Popular novels don’t often explore ideas or go off on tangents, but yours do.

JE: Certain readers have habits where they don’t really want to pause, ruminate, or luxuriate in a stray thought that might pertain to the action or not. They want to mainline the plot the whole way through, and they get very upset if the writer doesn’t do that. I don’t know if this was always the case or if we’re becoming more impatient as people and citizens.

I don’t like boring writers who describe everything, but I do like to encounter a mind superior to my own, a mind noticing things that I haven’t noticed about the world and making connections. When I encounter that in a book, I’m absorbed.

DS: Are you working on a screenplay for The Marriage Plot? That sounds exciting.

JE: I’m coadapting the novel for a screenplay, but I don’t know how to do it. It’s the opposite of exciting. I’ve already written the book, so it’s like taking dirt from a pile on one side of a room with a shovel and putting it on the other side—but it’s got to be a smaller pile and the right dirt. The exciting part is going to be when we fix it. I told them not to hire me, but they insisted.

Speaking of screenplays, I just saw The Great Gatsby and reread the book. I didn’t like either one of them. Anna Wintour saw the movie; she’s a friend of the director so she said, “It’s a spectacle that you cannot deny.” I think I’m going to use that. When people say, “How do I look today?” I’m going to say, “You’re a spectacle that I cannot deny.”