True to form: Rosanna Warren approaches her poetry with a painter’s eye for color and shape. (Photography by Anne Ryan)

A poet reckons with a fractured world

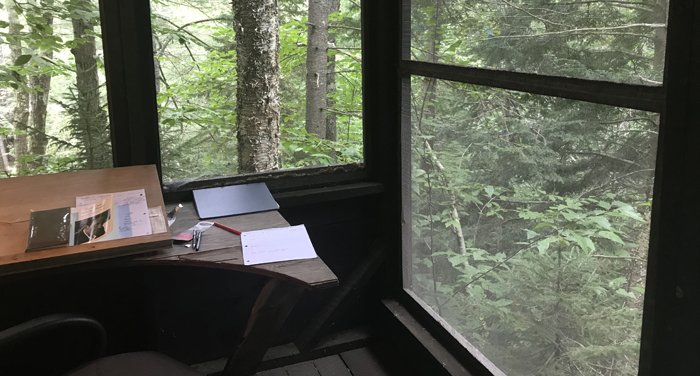

The place Rosanna Warren calls her “writing shack” is a tiny box of a building deep in the Green Mountains of Vermont that sits on a hillside at the edge of a vast, tumbling woods. From the outside, it looks about as large as a moderately generous walk-in closet, but once you step inside, the whole place deepens. There’s a small bench and bookshelf near the door, and on the other side of a thin partition, a built-in desk surrounded by windows that open out onto the forest. It feels like the world’s most private screened-in porch. Trees unfold into the distance—beech, birch, white pine, elm—and if you sit still, you can hear, amid the breeze and the birds and the gathering quiet, the sound of water in the stream below. Warren stands here, listening.

“So,” she says finally, “this is where I sit and take dictation from the brook.”

Today she has been taking dictation since about 8:30 in the morning. Now it’s close to 2 p.m., and time for lunch. This is the last weekend of August 2018, and her annual “summer migration” to Vermont is winding down. In a week, she will be on her way back to Chicago.

Warren is the Hanna Holborn Gray Distinguished Service Professor in the John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought, and a poet and translator whom critics invariably seem to wish more people knew about. In 2017 the Los Angeles Review of Books revisited Warren’s second poetry collection, the Lamont Poetry Prize–winning Stained Glass (W. W. Norton, 1993), and praised her “perspicacious vision that relentlessly seeks truth not despite but through the ‘stain’ of the full range of humanity.” In 2002 Stephen Yenser gushed that even Warren’s earliest work was “not only ‘promising’ but truly precocious, proof of a talent already ripe.” Writing in the New York Review of Books in 2011 about Warren’s Ghost in a Red Hat (W. W. Norton), released that same year, Dan Chiasson spoke of the “shimmering shapes she devises,” her “arresting” plainspokenness and, in her more outward-looking poems, a “significant contribution to the national imaginary.” “Warren,” he argued, “is not as well known as she should be.”

Her work is difficult to summarize. The style and subjects change from book to book, and from poem to poem. Most of the time she sticks to free verse, but not always. Some of her work is deeply personal: bracing elegies to her parents and to a close friend who died from breast cancer a few years ago. “Friendship is always travel,” Warren writes, en route to see her sick friend, “from the far country of my provisional health, / toward you in your new estate of illness, your suddenly acquired, / costly, irradiated expertise.”

Other work contemplates lost love, a failing marriage, aging, illness, the meaning of home, the comforts of music and poetry. In “Cotillion Photo,” a framed image from a bygone debutante ball (“These young women will last forever, posed like greyhounds”) sparks a memory from childhood and a meditation on time and transformation, destiny and self-determination, in life and in art. “What was to come / would come in its own good time / outside the frame.”

Other poems are overtly political. Warren has written mournful, angry, pungent lyrics about the depredations of Wall Street and the war in Iraq. After Hurricane Katrina, her younger daughter, now a social worker, went to New Orleans to volunteer with the recovery effort; Warren visited her there and helped rebuild homes that had been destroyed. Afterward she wrote about what she saw: “I lost count of slab after cement slab / where bungalows used to stand.” In “Earthworks,” a 15-page poem loosely set during the planning of New York’s Central Park, Warren imagines her way into the life and work of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, weaving details from his personal and professional experiences with meditations on civics and aesthetics, urban history, horticulture, the Civil War and slavery. It is a poem about designing a public park from the mud and muck of 19th-century Manhattan Island, but it is also a poem about trying to design a democracy from the “disunited, discordant parts” of American life.

At 66, Warren has a quiet intensity that persists even after her guarded cheerfulness relaxes into warmth. “I think in the last few years, I have wanted my poems to be permeable and even more wounded by experiences,” she says. That may sound like an exalted concept, but what she’s talking about is a kind of radical openness to the world around her, a way of approaching what others might call the human condition, or the fallen world, or the inherent strangeness and fracture of existence. It is also, for her, a way of setting aside the self to find something deeper. “I want my poems to be concerned, however obliquely, with the lives of people besides myself,” she says, “and with a sense of the larger relations that govern us, in justice and injustice.”

A lyric by the American poet Hart Crane helps illuminate what she means. “The Broken Tower,” written shortly before Crane’s death in 1932, is a kind of sacred text for Warren. It’s one of the many poems she knows by heart, and it helps guide her thoughts and actions, and her writing. One middle stanza reads like this: “And so it was I entered the broken world / To trace the visionary company of love, its voice / An instant in the wind (I know not whither hurled) / But not for long to hold each desperate choice.” To Warren, the poem speaks of “the sense of crucifixion at the heart of life,” she says: “the wound that opens us to reality, to the suffering of others, to the hugeness of being we cannot control.”

Allowing that uncontrollable hugeness to break the surface of a poem leaves a mark—“wounds” it—and disrupts the form, the normal symmetry and sense of orderly closure. Warren’s work bears this out; in recent years, her poems seem increasingly cracked open and almost physically broken: irregular lines, unpunctuated sentences, interrupted syntaxes, synaptic leaps, voices that collide abruptly. In 2018 Warren explained to the literary journal Five Points that she was allowing more of the outside world into the territory of her poems: “If something or someone wants to knock on the door and enter a poem, why not let that happen?” The poet’s job, she says, is to find the artistic “shapeliness” in all of this wounding experience, the music. From that comes meaning, comes beauty—and discovery. “That’s why poetry matters. … If it discovers nothing, it’s worthless.”

Like many poets, Warren is a scavenger and inheritor, and her life has been shaped by two powerful influences: the shared human legacy of classical literature—ancient Greek and Latin poetry infuse her work at an almost cellular level—and her own family history. She is the daughter of two celebrated writers: the poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren, and essayist and novelist Eleanor Clark. (In fact, the family is full of writers and artists: Warren’s brother, Gabriel, is a sculptor; her nephew Noah a poet; her niece Sofia a cartoonist; and her daughter Chiara makes a living as a social worker but is also a poet and nonfiction writer.) From Warren’s earliest memories, their home was full of words. Her father was always reciting poems, she says, and for her and her family, “telling stories was like breathing.” She grew up with the idea that writing was “just what people did.”

Much of that growing up happened here in rural Vermont, where her parents bought a small cabin in 1959, the year she turned six, and a few years later built a house on the same lot. During the school year, the family lived in Connecticut, where her father was a professor at Yale, but these woods were where they spent long summers and Christmas vacations, Easters and Thanksgivings, and weekends in between (especially winter weekends—Warren’s mother was a fanatical skier, and Mount Stratton, the highest peak in the southern Green Mountains, stands just five miles away). There was a tiny pond out front, where she and her brother used to swim, swinging out over the water on tree branches. And a creek where she once caught a trout using sewing twine, a safety pin, and a piece of bacon. Back in the woods stood the spring where Warren’s father would trek to get water for everyone’s baths during the years they spent in the cabin, which had no running water or electricity then. “In the winter, if there was six feet of snow,” she says, “he would have to dig a trench to get to the spring and then break the ice off the top with an axe and bring the water back in buckets.” One winter day, he carried in 27 buckets.

This is the place Warren still migrates to every summer. The writing shack where she works once belonged to her father. Like her, he wrote every day, from nine in the morning until two in the afternoon.

Warren’s early life with her parents seems to have been remarkably charmed. They were larger-than-life literary figures who were also loving and attentive to their children. The upbringing they gave Warren and her brother sounds almost mythical—“like a peaceable kingdom of weirdly docile geniuses, with a child in charge,” Chiasson writes—and yet also, in important and intentional ways, deeply grounded. Both parents had grown up poor: her mother in a “genteel but poverty-stricken family on a failed chicken farm,” Warren told Five Points, and her father in a small Kentucky town on the Tennessee border. His father had gone bankrupt during the Depression.

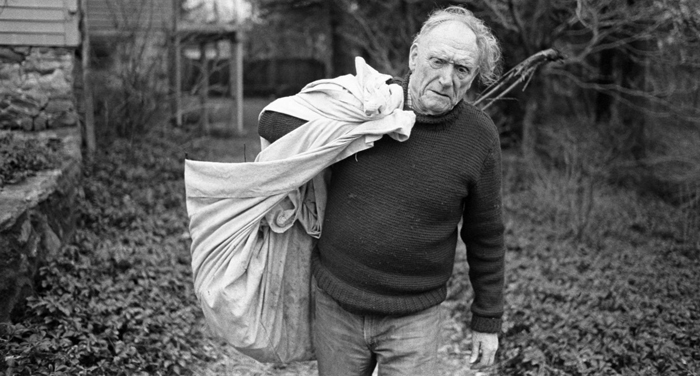

Those experiences stayed with them, and even after they became famous, Warren says, her parents resisted glamour. In the afternoons, when they finished writing for the day, they usually turned to some kind of physical work, her mother in the garden, her father building a stone wall or something else around the house. “There was a sense of being responsible for the physical reality we were in,” Warren says. Life was about making things: stone walls, vegetable gardens, art, stories, poems.

This intimate literary inheritance connected to a more universal one. Warren first encountered Greek and Latin poetry—and French and Italian literature, another influence—as a child traveling with her parents. Trips to foreign places gave her an early and sustained exposure to worlds and lives far outside her own, an awareness of wider human experiences. Usually the family went to tiny corners of Europe that were remote enough to be relatively inexpensive but also, in part because of their remoteness, somewhat fantastical.

Every summer until she was five, the family rented space in a ruined fortress near an Italian fishing village, owned by an old woman who was such a miser, Warren says, that she ate moldy spaghetti. The family cooked on a charcoal stove and ate in what had been the stables for the soldiers’ horses; they slept on cots in the barracks. Chickens and scorpions and a goat roamed the courtyard.

When Warren was 12, the family spent a year living in a village in southeastern France. For her, this was a turning point. She learned French and began memorizing poetry in school. She wrote poems in French too, imitating the rhythms and forms she saw in works by La Fontaine and Baudelaire (and later, Mallarmé, Apollinaire, Rimbaud—“these were my gods”). Perhaps even more crucially, she began studying Latin and translating ancient poems. The stanza shapes in Horace and Catullus were what thrilled her early on, and that excitement led her to other Roman poets, and to the ancient Greeks—Homer, Sappho, Alcaeus, Alcman.

Becoming a translator helped Warren internalize the classics—the beauty of their language and idiom and meter, but also their sensibilities and perceptions. And their imperishable stories. Her published work contains straight translations (a verse rendering of Euripides’s The Suppliant Women, for example) and plenty of looser interpretations (a string of prose poems titled “Odyssey”). But mostly the classics are just simply everywhere in her poetry: they animate her metaphors and sharpen her sense of irony, lend her work an understanding of tragic limits, of the complexity of moral and political meanings, of what it means to write “in the light of death” and to try to wring something permanent from what is temporary.

And so an elegy that compares Warren’s dying mother to a “crack Austrian skier” staring, petrified, down a plunging slope turns out to be an extended Homeric simile; in another elegy, her mother appears, 10 years after her death, as a vanishing orphic vision. A poem recalling long-ago airport goodbyes as a way of fathoming a sick friend’s passage into death (“we didn’t know / we were practicing”) is named after Charon, the underworld ferryman of Greek mythology. Even poems without overt allusion carry the classics in their bloodstream. Warren explained why to an interviewer from Columbia University a few years ago: “As much as I love poetry in Italian, French, English, these ancient poems, to me, have a concrete dramatic power that I don’t see anywhere else,” she said. “So, I want to steal that power. … It’s like putting your finger in an electric socket.”

For a long time, Warren resisted becoming a writer. Her earliest ambition was instead to paint. Looking back now, she says, the incandescence of her parents’ careers would have been too much pressure for her younger self. But also, she fell in love with the work of Henri Matisse. From the time when she was a child looking through art books and going to museums, paintings like French Window at Collioure, Goldfish and Palette, and The Red Studio astonished her: Matisse’s sculptural sense of form, his “abstracting force,” his sumptuous, dramatic colors and subtle shades of black and white.

And so Warren spent thousands of hours filling up hundreds of canvases, investigating shape and shade, the mystery of light and color and space, working to connect her inner world to the external one in front of her. At Yale she majored in painting and comparative literature and spent college summers in painting programs in Paris and New England. “I was almost trying not to write,” she says. “I was trying to paint.” And Warren never completely surrendered her first art. Its principles remain visible in her writing, and she still draws from time to time, “very privately, as a way of connecting with reality.”

But in her early 20s, she came to the realization that she wasn’t a painter. “It broke my heart,” she says. Unwittingly, she’d been spending more of her time on poetry, a practice she had also never surrendered. And there were “internal pressures that I couldn’t control,” she says, ideas and experiences she couldn’t express except in words. Three years after graduating from college, she enrolled in the creative writing graduate program at Johns Hopkins University and afterward spent 30 years teaching literature, creative writing, and translation at Boston University, before coming to UChicago in 2012.

In 2020, Warren will publish a long-term writing project that bridges—and in fact helped spark—her transition from painting to poetry. Max Jacob: A Life in Art and Letters (W. W. Norton) is a biography of the French painter and poet, whom she first discovered as a college student still intent on becoming a painter. While working in a Paris library to archive the painting papers of the Matisse contemporary André Derain, she ran across a mention of Jacob’s name and was intrigued.

Jewish and gay, Jacob underwent a mystical conversion to Catholicism and spent two seven-year periods living in a Benedictine monastery before being taken by the Nazis in 1944; he died from pneumonia in Drancy internment camp. Two early poems Warren wrote and dedicated to Jacob were the first she ever showed to anyone besides her parents, and their publication effectively marked the start of her professional writing career. Fascinated with Jacob’s life and work, she has spent the past 30 years working on his biography. As both a painter and a poet, “he was divided in a way that I was feeling divided,” she says.

This September she will also release a volume of selected poetry in French translation, De notre vivant (Æncrages & Co.), and in 2020 a book of new poems, her fifth. Titled So Forth (W. W. Norton), it compiles nearly a decade’s worth of writing. A sequence of poems called “Legende of Good Women” is at its core, the title borrowed from an unfinished work by Geoffrey Chaucer that narrates the lives of 10 famous women from antiquity and mythology. Warren focuses on an updated cast: Renaissance poet and translator Mary Sidney, fashion designer Coco Chanel, singer and songwriter Marianne Faithfull, harpsichordist Sylvia Marlowe. The poems wind themselves around concerns that run throughout the book: womanhood, sexual identity, art and power, the damage we suffer and inflict. “There are many ways / to throw oneself away,” Warren reminds readers in “A Way,” about Faithfull. So Forth, Warren says, “is deeply about forms of woundedness and wounding, remorse, and perhaps healing.”

Those themes play out sharply in another poem from the book, “For Chiara,” a deceptively slight lyric that returns to the woods of Vermont. On an evening walk, Warren and her daughter—who, the poem tells us, wants “to hold each wounded soul”—come across a garter snake injured by a passing car. Helpless to heal its agony, which they also cannot help but witness, they nudge the animal into the grass beside the road. It is autumn, and like the snake, the season bursts with a final wild vigor as death closes in: “fevered” and flaring, the crab-apple tree a “crimson pointilliste nimbus,” the crackling leaves underfoot “tinder, kindling” ready to catch fire.

But autumn, Warren writes, “croons an old song,” and dust scuffs their feet as they walk. Alluding briefly to a story about the Gorgons, the snake-haired women of Greek mythology, the poem gestures toward an inherent, unavoidable connection between the power to heal and the power to kill. After Warren and her daughter edge the snake off the road, the poem asks, “Do we stop seeing / when we walk away?” That question hangs in the air as the final lines exhale: “The brook prattles on. / Home’s far off. Dusk settles, slowly, among leaves. / That’s not mercy, scattering from its hands.”

Read two poems by Rosanna Warren.

Lydialyle Gibson is an associate editor at Harvard Magazine.

Updated 08.15.2019 to clarify that Warrenʼs book So Forth will be coming out in 2020.