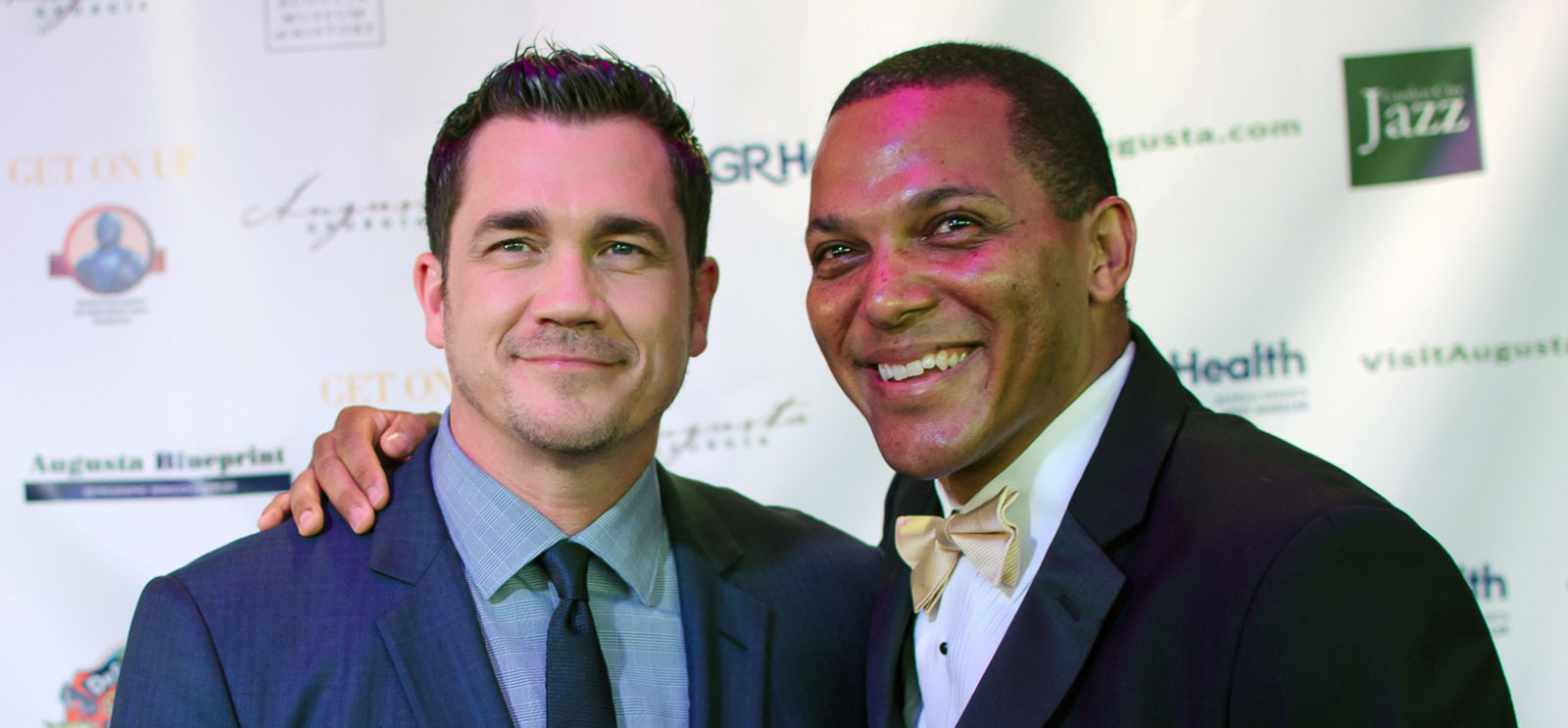

Greer, right, joined director Tate Taylor at the premiere of Get On Up. (Photography by Ryan Wehmeyer/The Augusta Chronicle)

Happy in his corporate day job, a Chicago Booth graduate pursues Broadway producing on the side.

When David Greer, IMBA’99, describes his second job as a theater producer, he’s straightforward about his role. “Basically, trying to find wealthy individuals who want to invest their money into a risky investment,” he says. “I’m not sure if I’d call it investment—into risky passion projects.”

In 2010 Greer helped produce the Broadway musical The Scottsboro Boys, which earned 12 Tony nominations, and he has since helped bring to the stage productions of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, The Mountaintop, and other projects.

By trade Greer is a numbers guy—he spent time in the finance and business development divisions of Pratt & Whitney, an aerospace company, and now works for Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati, Ohio. He doesn’t shy away from a straight quantitative assessment of how elusive financial success has been. “When you look at Broadway’s top 10 grossing shows, I’m not in any of those numbers,” says Greer. “I’m not even in the top regional shows.”

I met Greer in New York, during one of many trips he’s made to the city in recent years since a chance meeting with an actor he admired, Colman Domingo, turned Greer onto the theater world’s niche of part-time financial producers. An email over LinkedIn got Greer a meeting with a producer for The Scottsboro Boys, who happened to be looking for others to join the team. “I’m not afraid to introduce myself to people that I don’t know. I’m not afraid of being turned down.”

That self-assurance is a requisite trait in the corporate world, and it’s served Greer well when pitching “risky passion projects” too.

“Even the best batters in baseball, at best, hit three out of 10 times. So if I get turned down this time, I’m gonna keep taking a swing until I get a hit,” says Greer. “I’ve had a lot more strikeouts than hits.”

While most of Greer’s work as a producer has been on the financing side—identifying, attracting, and negotiating with investors—he has also done the operational “grunt work.” For Black Stars of the Great White Way, a one-night concert celebrating the legacy of black men on Broadway, Greer and the operations team coordinated performers’ travel schedules, negotiated a contract with Carnegie Hall, and even maintained the show’s Facebook page.

It was a theater connection that got him closest to realizing his dream project—a musical about the life of James Brown. After learning that a movie script was already in the works, with Mick Jagger producing, Greer knew that his vision of the Broadway production would have to wait. But a representative of Brown’s estate did like his proposal.

“They asked me if I’d quit my day job to join them to help make the movie. And the only catch was, there was no salary.” Though he declined the offer, Greer did get a small, nonspeaking part in Get On Up—the Godfather of Soul steals his date at the Apollo.

Greer recently added another role to his résumé: playwright. Hour Farther, a play he finished in 2009 about an adopted son looking back on the father figures in his life, was staged in Mystic, Connecticut, last October. When I met him, Greer had just attended a reading of the play, looking to gain traction with artistic directors in New York.

Given the time he devotes to theatrical pursuits, it’s easy to forget that Greer has a day job. The theater work, Greer says—raising funds, pitching projects, writing, and the occasional acting gig—is all squeezed into holidays, personal days, lunch hours, and early mornings. The realm of theater and film offers a space for Greer to have an artistic influence, he says. But he’s irked by acquaintances who suggest that these are his true goals.

“I like what I’ve done in the business world. If my hobby was playing golf or softball or fantasy football,” no one would mention it, Greer says. “But because it’s this stuff, they think, ‘Oh, your priorities are off.’”

Then again, he recognizes, perhaps more than most, what a tough business theater is compared to his corporate experience.

“You could be hot one minute and cold for the next 10 years,” Greer says. “This is a much more risky world.”