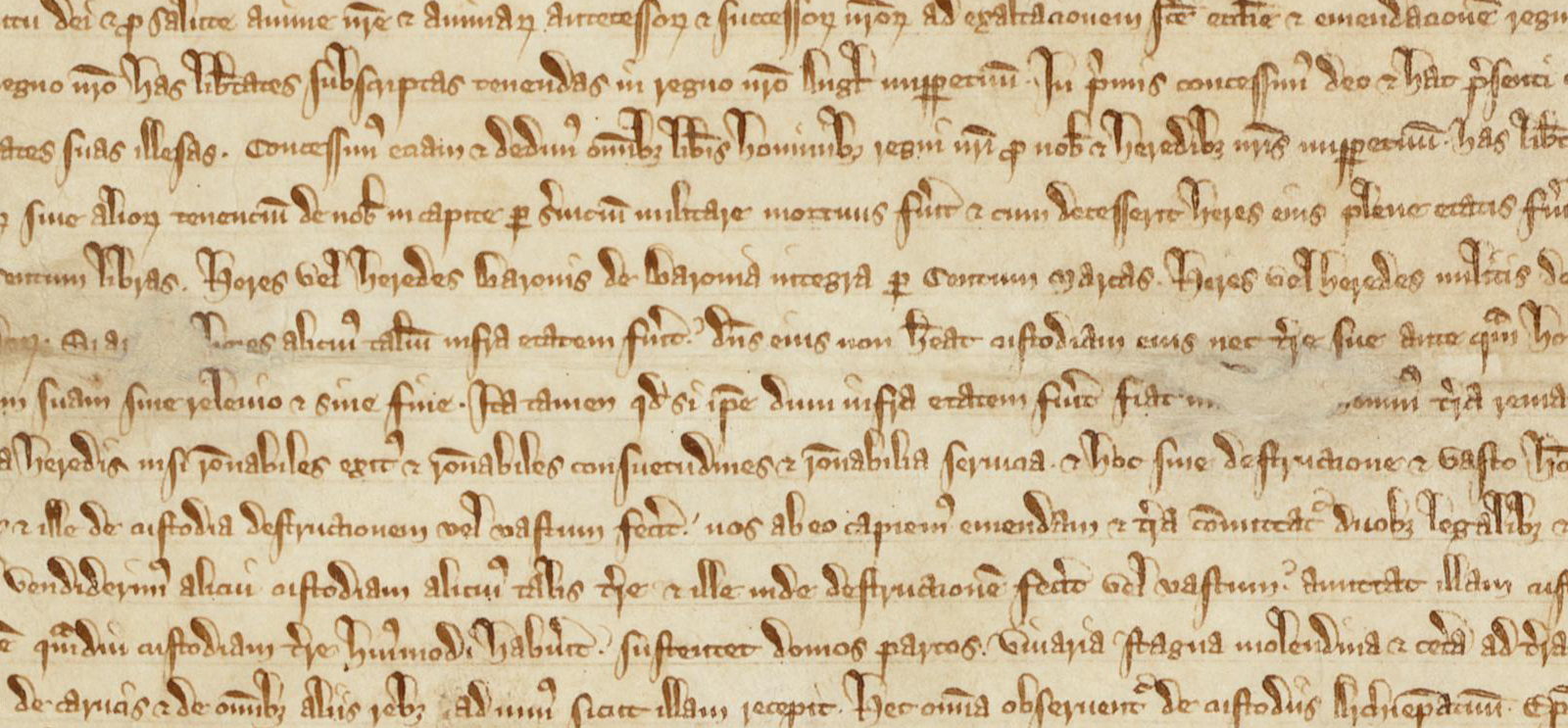

An up-close view of the only copy of the Magna Carta in America. (All photos courtesy David M. Rubenstein)

As the historic document turns 800, David M. Rubenstein, JD’73, reflects on preserving a Magna Carta in the United States.

One evening in December 2007, University trustee David M. Rubenstein, JD’73, found himself in a small side room at Sotheby’s New York City auction house, the new owner of the only copy of the Magna Carta in America. The $21.3 million purchase was nearly a surprise even to him; he had learned of the sale only the day before—and of the wrinkle that inspired him to bid, the expectation at Sotheby’s that the document was destined to leave the United States.

The first Magna Carta contains 63 clauses enumerating the rights of 40 rebel barons whom King John sought to appease when he put his seal on the document in 1215. Only 10 weeks later, the charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III at John’s request. In 1297 King Edward I enrolled a revised version on the statute books; this is the version that Rubenstein bought.

This year, the Magna Carta’s 800th, saw much celebration of the document, whose declaration of rights is widely regarded as a foundation of American democracy—widely, but not universally. “It is hard to think of an historical event in which the divide is any greater between the general treatment and scholarly treatment of the same document,” wrote Richard Helmholz, the Ruth Wyatt Rosenson Distinguished Service Professor of Law, in a recent essay. “The ‘popular view’ holds that contemporary principles underpinning democratic liberties can be traced back to Magna Carta,” he elaborated. “The ‘scholarly view’ takes pretty much the opposite position. Magna Carta was a baronial document, occasioned by a conflict with King John and aimed at entrenching baronial privileges.”

But, Helmholz argues, “an old precedent can be given new life.” From 1215 to 1297 to the 17th century, when English lawyer Edward Coke resurrected the document, championing it as a way of checking the power of the Stuart kings, the history of the Magna Carta shows its ongoing capacity to inspire support for civil liberties “in circumstances very far removed from its original context.” Those circumstances include the American colonies’ fight for independence and many present-day political causes.

Rubenstein’s Magna Carta, written in iron gall ink on sheepskin parchment, is on long-term loan to the National Archives. There it is the centerpiece of the David M. Rubenstein Gallery. The gallery is also home to the permanent exhibit Records of Rights, which traces the history of immigrants’, African Americans’, and women’s rights in the United States. The first thing you see on approaching the gallery, the Great Charter seems to glow from beneath its protective low light. Its state-of-the-art airtight case is also on loan from Rubenstein, who hired the National Institute of Standards and Technology to develop the best possible housing for the fragile document.

The purchase and loan of the Magna Carta is just one facet of Rubenstein’s prolific philanthropy. A signatory of the Giving Pledge started by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, he has committed to donate the majority of his wealth to philanthropic causes. Many of Rubenstein’s causes are centered in Washington, DC, where he supports the National Zoo’s panda program, led the effort to repair the Washington Monument after it was damaged in an earthquake, and chairs the board of trustees of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

At UChicago, he established the Law School’s David M. Rubenstein Scholars Program in 2010, citing his gratitude for the scholarship he received when he attended. In 2013 he renewed the program, which provides full-tuition, predominantly merit-based scholarships to 20 students in each Law School class. The Rubenstein Forum, an innovative facility for conferences and collaboration on campus, will be named in recognition of his generous gift last year. When it opens in 2018, the building will “contribute significantly to the University’s character as an intellectual destination,” said President Robert J. Zimmer in announcing the gift.

In an interview adapted and edited below, Rubenstein, cofounder and co-CEO of the Carlyle Group investment firm, spoke to Helmholz and the Magazine about the Magna Carta’s history and legacy, the other documents it has inspired him to collect for public display, and the broader “patriotic philanthropy” he is known for.

Symbolic weight

The Magna Carta probably means more to people in the United States than in England in many ways. The 1215 document was abrogated and never went into effect. The 1297 version did go into effect, but in the 1300s and 1400s, the parliament was becoming more important than the king, so the Magna Carta, which checked the powers of the king, held less sway.

It wasn’t until Edward Coke came along in the 17th century, and William Blackstone [who published the first scholarly edition] in the 18th century, that its importance grew again. They revived it. And our founding fathers, when they started getting taxed, kept saying, “No taxation without representation.” That was in the Magna Carta. In effect they were saying, “We have the rights of Englishmen.”

That was what really led, I think, to the Revolution. People said, “We have these rights, and you’re violating them.” It’s more complicated than that, of course. But the early writings of the founding fathers do reference the Magna Carta, particularly when they’re making pleas to the king of England and others to get rid of the taxes.

Making a down payment

I was flying from London to New York and going through my mail that had accumulated. One email was from an investment banker who said, “We’d like you to come to a reception at Sotheby’s.” It was that night, to look at the Magna Carta.

So I said, “OK, you got my interest.” I’d go, I’d meet the investment bankers, maybe some good business would come, and I’d see the Magna Carta. Because of delays, I got there late. It was only about 10 minutes before the exhibition was over and everybody was gone except the curator.

She explained to me that there were 17 copies, and this one was likely to go to somebody outside the country. It seemed like a good idea to try to keep it in the country. I thought one of 17 should be here. So I decided to come back the next night. I didn’t want to tell anybody, because I didn’t want to seem presumptuous. They put me in a little room, put in a telephone, and I listened. And, honestly, I couldn’t hear that well. I couldn’t tell what the bids were. Then when I put the final bid in, they said, “Sold.” I wasn’t clear if it was me or not.

David Redden, the auctioneer and head of books and manuscripts at Sotheby’s, came in. He said, “Okay, you won, who are you?” I’d never been there before. Then he said, “You can slip out the side door, or there are reporters.” I went out and talked to the reporters. I said I was happy to tell them I was going to give it as a down payment on my obligation to repay my country.

Spur of the moment

If I’d said, “How do I want to help my country in some way? I have some money, what can I do?” and hired McKinsey or BCG or Bain to do a study, I’m sure they would have come back with lots of great ideas. But I’m finding that the best ideas often come to one spontaneously.

It’s like many things in life—you don’t know where they’re going to lead. Afterward people started calling me with other rare documents. I said, “I only did this as a one-time thing.” But I started buying them: a Declaration of Independence, the 13th Amendment, the Emancipation Proclamation. I had the idea to never put them in my house, but instead put them on display in places around the city. I make them on permanent loan, and this is the reason: If you give something to an organization, once it’s theirs, they can display it or not display it, and you lose control. My goal is to make sure that people can see them and learn about them.

Virtue in knowledge

Recently there was a survey of Americans that asked which river George Washington crossed in 1776. And 35 percent of Americans said the Rhine River, which happens not to be in our country. Who was the first treasury secretary? The answer of about 30 percent of Americans was Larry Summers, which is not the case.

Another survey, of high school sophomores, showed that more could name the Three Stooges than could name any three founding fathers. So I’m trying to do a little bit to get people to know more about history, on the theory that if you know more about history, you’ll be a better citizen, and that better citizens make a better country.

Declarative acts

Recognizing that the Declaration of Independence was fading, John Quincy Adams, when he was secretary of state, said, “We ought to have a perfect copy of this before it fades completely.” They hired William J. Stone, a printer from Washington. Over three years he came up with a printing process to make a perfect copy. It was, essentially, taking a wet cloth and putting it on the original document, which took off half the ink. He put that on a copper plate, and they made 201 copies.

When you see a copy of the Declaration of Independence in the New York Times on the Fourth of July, it’s not the original document, which has faded too much. You’re seeing one of the Stone copies. There are about 30 left, and I own a few of them. I’ve put one in the National Archives, which didn’t have one; one at Mount Vernon; one at the State Department; and one at the Constitution Center.

Philanthropy in action

Philanthropy is an ancient Greek word that means “loving humanity.” You don’t have to be wealthy to be a philanthropist, although we’ve bastardized the word. I tell people, give your time, your energy, your ideas. You can help other people. I also say, you’ll probably get to heaven more quickly. Now, I can’t prove it, but why would you want to take a chance? So try to help other people.