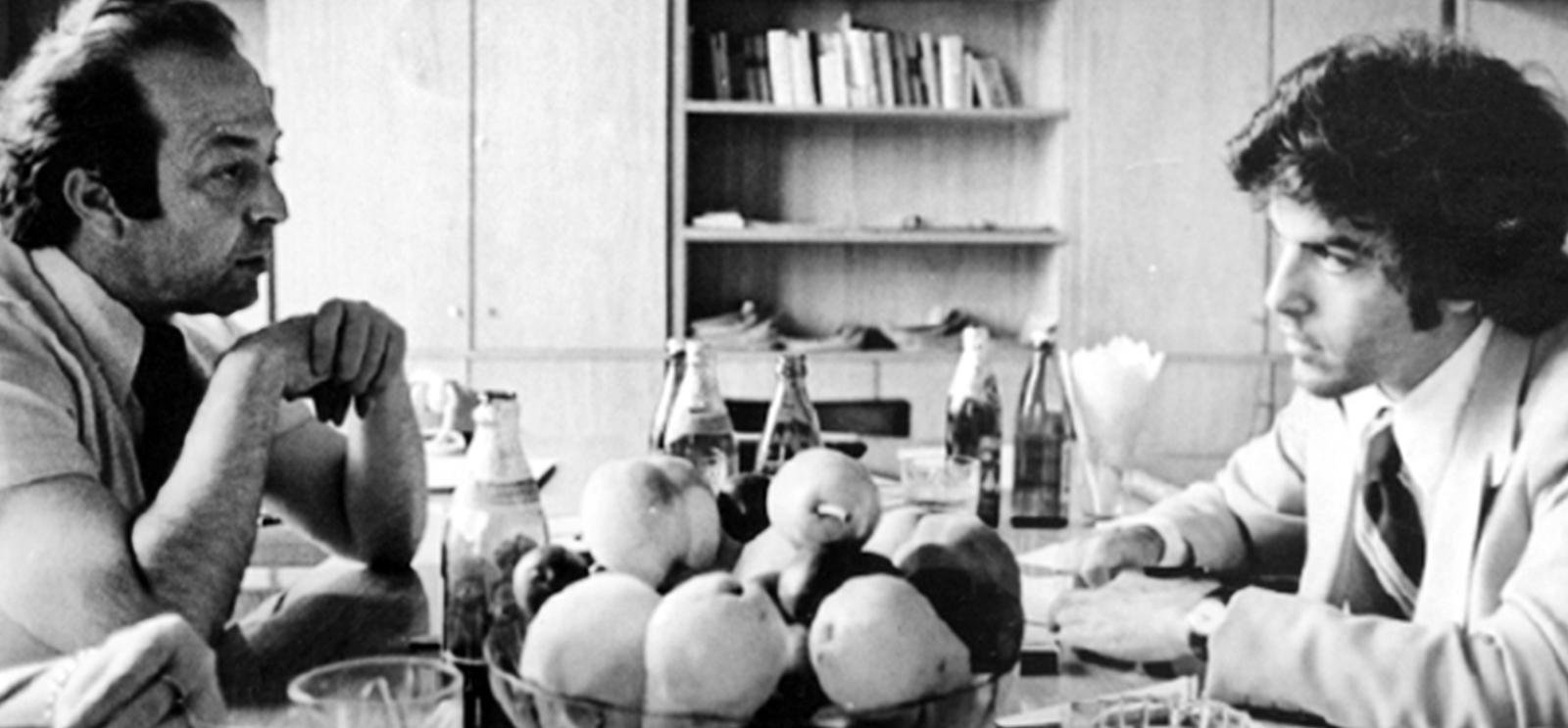

Back in the USSR: Satter (right) interviews a journalist in the Republic of Georgia (1978). (Photo courtesy David Satter)

On a peaceful night in June 1980, I was on a train from Moscow to Vilnius. In my compartment were a man and a woman, both Soviet citizens. The man was an engineer at a power station outside Moscow. The woman was an economist in Vilnius.

Rolling by outside the train’s windows were forests and lush green fields lit by the fading light of a blood-orange sun. Taking advantage of the encounter with an American journalist, my fellow passengers decided to engage me in a political discussion.

“First of all, you have to begin with the basics,” the man said. “In America, you’ll have to admit, money determines everything.”

“That’s right,” the woman said, “the corporations control everything.”

I said that in a democracy, the behavior of the corporations is limited by the law.

The engineer waved his hand in disgust. “The law,” he said. “That’s nonsense. The law is what the corporations want.”

I noted the resignation of President Nixon. “You see,” I said, “even the president isn’t above the law.”

“Yes,” he said, “but the president isn’t the real power. The real power is the corporations, the Rockefellers.”

I arrived in Moscow in 1976, eight years after graduating from the U of C, and was to spend the next six years reporting there. The question that dominated my term in Moscow, when the Soviet Union was at the height of its power, was the one that first occupied me when I was an undergraduate: to what extent is “political virtue” worth the price of living in a world of lies?

The Soviet Union saw itself as the quintessence of political virtue, and it was the crystallization of a lie. Soviet citizens could not vote, write, speak, or travel freely, but they were told that they were the freest people on earth. Others dreamed of paradise in the next world, but Soviet citizens did not need the hereafter. (This was a good thing because when Yuri Gagarin went into space, he looked for God and did not see him.) The Soviet Union had created heaven on earth.

What existed in the Soviet Union was an entire false reality that came to be so taken for granted that its surrealism was not appreciated. Newspapers contained only one opinion, trade unions supported management, and the parliament approved without dissent everything submitted by the government’s executive branch. The entire society was said to be unanimous (except for a few renegades, mostly traitors in the pay of the West), and the regime, steered by Marxist-Leninist ideology as inarguable as the axioms of geometry, was infallible.

The false world of the ideology dominated in the Soviet Union during all of the years I was in Moscow as the correspondent of the Financial Times. As a result, I felt as if I had a front-row seat at a nationwide theater of the absurd. But this theater could not withstand the impact of truthful information, which is what it faced after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and initiated the policy of glasnost.

The intention of glasnost was to aid in the liberalization of the system. It was supposed to make socialism more dynamic, yet it had the opposite effect. The introduction of truth into an integrated system based on lies completely undermined the latter, and in six short years the Soviet Union collapsed.

I was persona non grata after leaving Moscow in 1982, but the changes under Gorbachev made it possible for me to return in 1990. I therefore witnessed the Soviet collapse and the birth of the new Russia. Unfortunately, the practices of the Soviet Union were not laid to rest when the country itself disappeared. In particular, the glorification of the goals of the state (and contempt for the fate of the individual) was carried over into the new Russia, where the attempt to go from socialism to capitalism without the rule of law led to the complete criminalization of the country. When Vladimir Putin took over from Boris Yeltsin and Russia’s economy finally began to grow as a result of the sharp increase in world commodity prices, the result was not the implanting of democracy but the glorification of the past and a new authoritarian system.

Under Putin there was little civic activism in Russia. For the most part, the population was ready to ignore lawlessness and lack of democracy as long as the rise in their standard of living continued. When the Putin regime blatantly falsified the December 2011 parliamentary elections, however, thousands of people finally took to the streets in the biggest demonstrations in 20 years.

The demonstrations are set to continue. As a result, Russians now have a second chance to create the democracy that they failed to establish after the Soviet Union’s fall. But to do so, they have to free themselves of the remnants of the imaginary world of the Soviet Union, including the notion that the Russian state is somehow sacred and its judgments infallible. This will only be possible if they face the full truth about the past and commemorate the millions of victims of the Communist regime’s crimes.

In 1992–93 I again lived in Moscow and witnessed the chaos as anti-Communists tried to create capitalism using Bolshevik methods, and in the following years I traveled to Russia perhaps 70 times. My experience there led to three books: the first, Age of Delirium: The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Union (Yale University Press, 2001), has been made into a documentary film that premiered this past fall in London and Washington. All three books chronicle the history of Russia in our times as I was privileged to see it.

On March 4 Russia will vote for president, and a new confrontation is brewing between the country’s democratic forces and a corrupt regime. This is a confrontation that the democratic forces need to win. Russia is too great a country to live forever under the yoke of falsehood. At the same time, they need to win for the benefit of the rest of the world, to demonstrate once and for all the danger of accepting the temptation rejected by Christ in the wilderness—the exchange of truth for bread.

David Satter has written three books on Russia, most recently It Was a Long Time Ago, and It Never Happened Anyway (Yale University Press, 2011).

Video

David Satter, AB’68, analyzes the return of Putin and what it means for US-Russia relations.