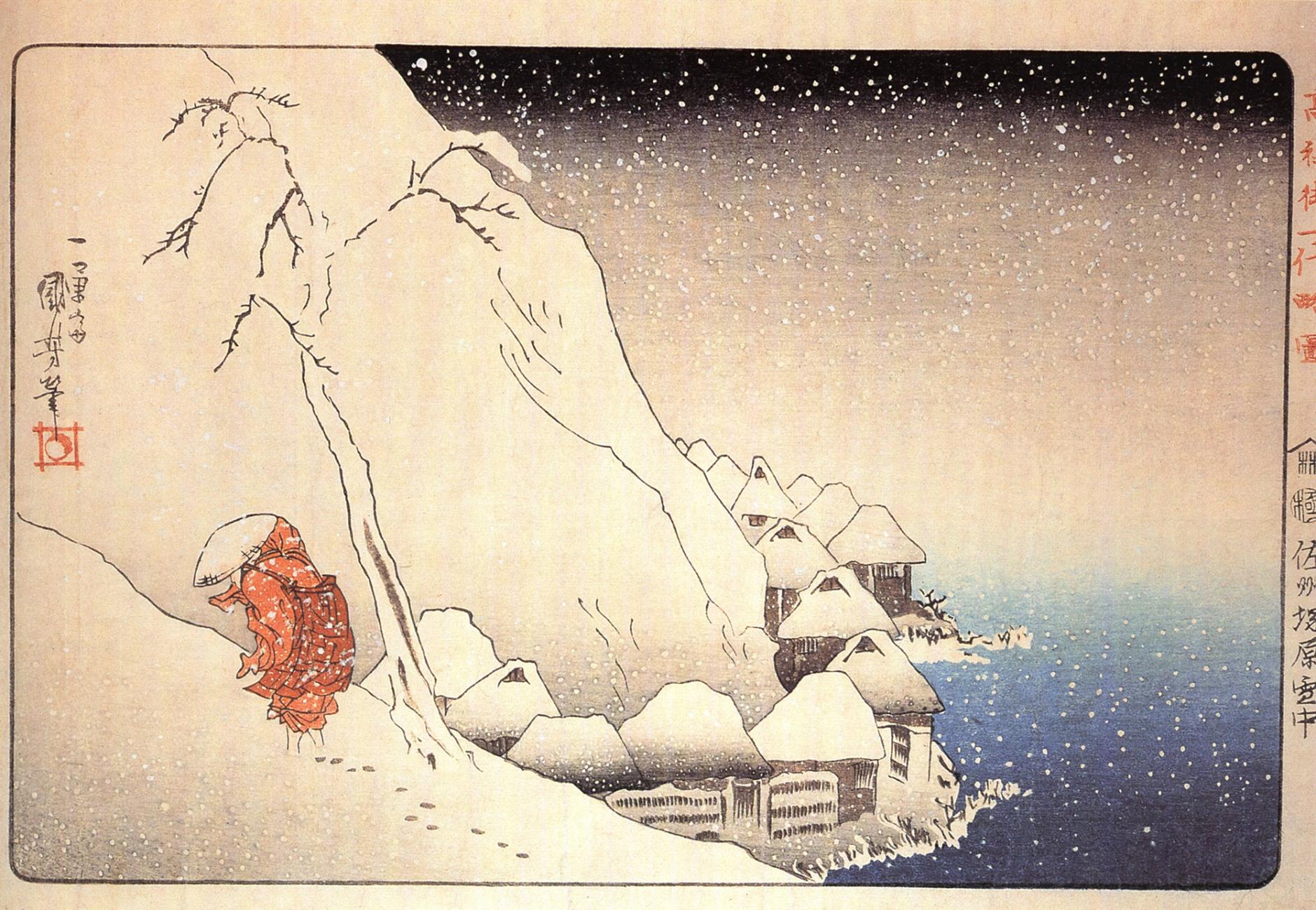

Lickerman’s experience with Nichiren Buddism has taught him techniques to achieve “personality hardiness: the capacity to survive and even thrive under difficult conditions.” (Public domain illustration of Nichiren Daishonin)

Alex Lickerman, AB’88, MD’92, explains how to construct an indestructible self.

Six months into my second year of medical school, the first woman I ever loved brought our year-and-a-half-long relationship to an end, causing me to fall immediately into a paralyzing depression. As a result, my ability to study declined dramatically—and as a result of that, six months later I failed Part I of the National Board Exam.

It was a devastating blow, not just to my ego, but also to my potential future: if I couldn’t pass the Boards, I wouldn’t be allowed to graduate medical school. I had no idea what to do. My thinking spiraled in useless circles as I hunted for a solution, my depression intensifying as none appeared, and soon I found myself crouching at the edge of despair.

I didn’t consider it at the time, but I wasn’t alone in feeling this way. Even before the US economy nearly collapsed in 2008, data from the National Comorbidity Survey told us that an astonishing 50 percent of Americans report having suffered at some point in their lives from a psychiatric disorder, most commonly depression, alcohol dependence, social phobia, or simple phobia. In fact, research shows that Americans have only a 35 percent chance of rating themselves “very happy” by the time they reach their late 80s.

But things aren’t as bleak as they seem. Or rather, things are only as bleak as they seem, for the way events impact us depends far more on the lens through which we view them—our inner life state—than on the events themselves. Not that mustering up courage, hope, and confidence in the face of adversity is easy. Viktor Frankl was only half right when he argued in his book Man’s Search for Meaning that we have control over how we respond to what happens to us. In fact, often we don’t—at least, not how we respond emotionally to what happens to us.

But Frankl wasn’t entirely wrong, either. Though absolute control over our response to adversity may elude us, influence over it need not. If we can’t change our emotional reactions by force of will, we can at least increase the likelihood that our reactions are constructive by cultivating something psychologists call personality hardiness: the capacity to survive and even thrive under difficult conditions. I’ve come to call this kind of hardiness an undefeated mind.

What does it mean to possess an undefeated mind? Not just that we rebound quickly from adversity or face it calmly, even confidently, without being pulled down by depression or anxiety, but also that we get up day after day and attack the obstacles in front of us again and again and again until they fall, or we do. An undefeated mind isn’t one that never feels discouraged or despairing; it’s one that continues on in spite of it. Even when we can’t find a smile to save us, even when we’re tired beyond all endurance, possessing an undefeated mind means never forgetting that defeat comes not from failing but from giving up. Possessing an undefeated mind, we understand that there’s no obstacle from which we can’t create some kind of value. Victory may not be promised to any of us, but possessing an undefeated mind means behaving as though it is.

The kind of Buddhism I practice, Nichiren Buddhism, is named after its founder, Nichiren Daishonin. Currently, 12 million people all over the world practice Nichiren Buddhism. It doesn’t involve meditation, mindfulness, centering oneself, or learning to live in the moment, as do most other forms of Buddhism, but rather something even more foreign and discomforting to those of us raised in the traditions of the West: chanting. Every morning and every night I chant the phrase Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with a focused determination to challenge my negativity and bring forth wisdom.

And over 23 years of Buddhist practice, wisdom has indeed emerged for me—and often in the most surprising ways. After spending many months of such chanting to free myself from the anguish that the loss of my girlfriend had caused me, I realized one morning that my suffering wasn’t coming at all from that loss, but rather from the misguided belief that I needed her to love me to be happy. I’d always known intellectually this wasn’t true, but not until that moment in front of my Gohonzon (the scroll to which Nichiren Buddhists chant) did that knowledge become wisdom—that is, become how I felt. I hadn’t, in other words, merely achieved a greater intellectual understanding that I didn’t need a woman’s love to be happy, but rather an emotional belief. And in the act of coming to know it in this way, my suffering ceased.

I was flabbergasted. How had this happened? Only after some time had passed did I come to accept that it had been the transformation of intellectual knowledge into wisdom by insight that had freed me from suffering. But as to the possibility that chanting a phrase over and over had turned a new idea into a belief imbued with the power to end my suffering—well, frankly, it was preposterous. And yet the possibility that this transformation had taken place serendipitously seemed equally unlikely to me. So, because I couldn’t split myself into one person who continued to chant and one who didn’t to see which became happier, I resolved to continue chanting to see if other insights would follow.

To my surprise, they did, several times in as many months. A skeptic to my core, I nevertheless began to find myself viewing a series of life-changing revelations less and less as coincidences and more and more as evidence that chanting did have the power to catalyze aversive life experience into an engine for growth, to shatter delusions of which I remained unconscious but that nevertheless limited the degree of happiness I was capable of experiencing. Whether by a general meditative effect (something supported by a growing body of research) or through the activation of some as yet uncharacterized force inherent within my life, I didn’t—and still don’t—know.

So I continued, reminding myself that subjective experiences can be scientifically investigated even when the investigator is investigating himself. However, because the insights I’ve attributed to my practice of Nichiren Buddhism have never come with any regularity, many of my non-Buddhist friends and family have been prompted to ask just how confident I can be that chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo has caused all the life-changing revelations that have come my way since I started practicing Buddhism. To this I’ve continued to offer the same answer since experiencing that first insight over twenty years ago: that I’m just confident enough to continue looking for more definitive proof.

So my experiment goes on, the scientist in me continuing to argue with the Buddhist, not only demanding more convincing evidence that chanting generates wisdom, but also trying to understand the mechanism by which it does so—one couched in terms of established physical, chemical, and biological laws that provides a natural rather than supernatural explanation. The Buddhist, however, reminds the scientist that I don’t entirely understand how my car works either, but I still get into it every morning and drive it to work.

Alex Lickerman is assistant vice president for Student Health and Counseling Services. This essay is excerpted from his book The Undefeated Mind: On the Science of Constructing an Indestructible Self. Lickerman identifies nine principles for developing resilience of mind in chapters including “Expect Obstacles,” “Stand Alone,” and “Accept Pain.” Copyright 2012 by Alex Lickerman. Reprinted with the permission of the Permissions Company Inc., on behalf of the publishers, Health Communications Inc.