Ted Rosenthal’s jazz opera, based on the experiences and letters of his father and grandparents, explores themes of grief, survival, and memory. (Photography by Sarah Shatz)

Erich Rosenthal, AM’42, PhD’48, escaped Nazi Germany to attend UChicago. His parents remained and perished. Decades later, his son Ted Rosenthal has memorialized their tragic family history in music.

For decades, the cardboard box of letters sat in the attic of the Long Island house where jazz pianist Ted Rosenthal grew up. He and his sister, Barbara, might have had “some vague knowledge that they existed,” he says, “but no one looked at them, no one discussed them.”

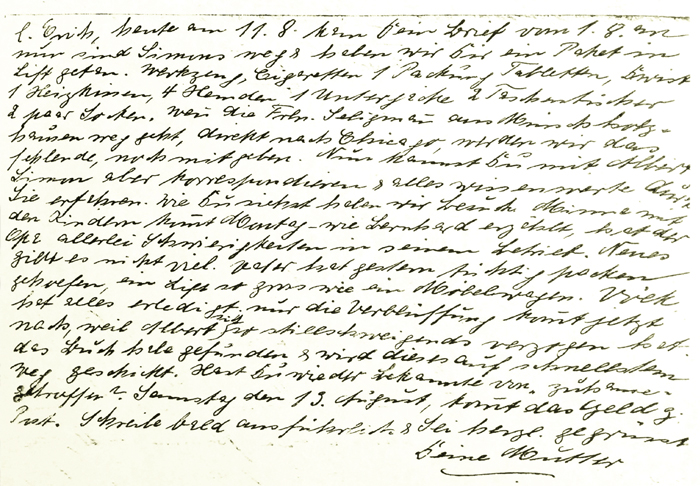

After his father, sociologist Erich Rosenthal, AM’42, PhD’48, died in 1995, Ted finally looked in the box. Inside were more than 200 letters sent by his grandmother Herta in Wetzlar, Germany, to her only child, then a sociology graduate student. The letters, dated from 1938 to 1941, were neatly filed in chronological order, along with duplicate copies.

Ted Rosenthal doesn’t know German. His mother was of Russian heritage and spoke a bit of Yiddish, “but the Germans looked down on Yiddish,” he says. “So we just spoke English at home.” He closed the box and put it in his own attic in Scarsdale, New York, where it gathered more dust.

Those long-neglected letters are the basis for Rosenthal’s jazz opera, Dear Erich, which had its premiere at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York this past January. His wife, Lesley, helped choose the letters and cowrote the libretto. Commissioned by the New York City Opera and presented with the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, “it’s a simple and fluid production, sensitively directed,” according to a New York Times review. The opera features 15 characters and 11 instrumentalists, including Rosenthal on piano.

The project began unexpectedly in 2015, when Rosenthal traveled to Bad Camberg, Germany, where his grandmother had grown up. He and 30 other descendants of the town’s Jewish community had been invited to attend the opening of the refurbished Alte Jüdische Schüle (old Jewish school), a half-timbered building that served as the town’s synagogue from 1773 to 1838. When Rosenthal told Peter Schmidt, the director of the local historical society, about his grandmother’s letters, Schmidt offered to translate them.

Back in the United States, reading the letters in English, Rosenthal discovered the voice of a grandmother he had never known, whose understated language and wry humor mirrored his father’s own. “A whole world began to open up, a world of family, family friends, people and places that were a fundamental part of my father’s growing up,” Rosenthal writes on the Dear Erich website. His father had never talked about any of it, “no doubt because it was too painful.”

Soon afterward, Rosenthal had to have a tumor removed from his left arm—a potentially career-ending surgery for a pianist. During his convalescence, when he wasn’t able to play the piano at all, he decided to dedicate his time to composing a jazz opera based on his grandmother’s letters.

Erich Rosenthal started his academic work at the Universities of Giessen and Bonn. He published two articles early in his career, both on the struggles of Jewish communities in Germany. In 1937 he began a correspondence with Louis Wirth, PhB 1919, AM’25, PhD’26 (1897–1952), a leading figure in the Chicago school of sociology.

Wirth, who was born in Germany, focused on urbanism. His first book, The Ghetto (University of Chicago Press, 1928), drew partly on his own experience to describe how Jewish immigrants adapted to urban life. “This young man seems to have some stuff in him,” Wirth wrote to Robert Redfield, LAB 1915, PhB’20, JD’21, PhD’28, then dean of the Division of the Social Sciences. “Would there be any possibility, even at this date, to get some help for him in the form of a full or half scholarship?”

There was not. All the funding had already been allocated. Nonetheless Wirth offered Erich a spot in the sociology program. With the help of an aunt in New Jersey, Erich was able to leave Germany in March 1938, eight months before Kristallnacht. “Maybe once, maybe twice, my father did say something to the effect that Professor Wirth saved his life,” Ted Rosenthal recalls.

During the first three years of Erich’s graduate study, his mother wrote about once a week. In the early letters Erich’s father, Theodor (after whom Ted is named), would occasionally add a businesslike postscript. Rosenthal used snippets of “between 10 and 20 letters” to construct the plot of Dear Erich.

An expert on assimilation and intermarriage among American Jews, Erich Rosenthal taught sociology and anthropology at Queens College, City University of New York, from 1951 to 1978. In 1963 he published data showing that intermarriage with non-Jews was much more common than believed, and that 70 percent of children in mixed marriages were not raised Jewish. His findings were reported in the New York Times, Time, and Newsweek. According to Rosenthal’s obituary in Footnotes, the American Sociological Association newsletter, “the issue provoked a crisis of soul searching about Jewish identity.”

The opera shows Erich as an old man in the last days of his life, consumed with guilt that he survived the war but could not rescue his parents. His relationship with his children, Freddy and Hannah, is strained and distant. (This was exaggerated for dramatic purposes, Rosenthal is quick to point out.) As Erich talks with his children, his past is revealed through a series of flashbacks.

In the first letter, as Rosenthal calls it, Erich’s mother wants to know all the details of his new life in America: How was the trip, how is the food, who is washing his clothes? “Very motherly,” Rosenthal says. “And this went on the whole time, even when she was really in peril.”

All too soon comes the Kristallnacht letter, actually a composite of two letters written a couple of weeks apart. Knowing the mail is censored, Herta writes obliquely that “your father and uncle have gone away”; in other words, the men had been rounded up and taken to a concentration camp. When Erich’s father returns, he is in such poor health that he dies shortly afterward. Composing music to this letter “was particularly intense,” Rosenthal writes on the opera website. “The words put to music magnify the emotion.”

In the immigration letter—another composite—Herta writes about how grim the situation has become and asks Erich to help her join him in Chicago. The “heartbreaking nitty-gritty detail” in these letters gave him a sense of the guilt his father must have felt, Rosenthal told the Jazz Times: “At one point she was literally packing, making a list of what she could take.”

In real life Erich never knew exactly what had happened to his mother after the letters stopped. Rosenthal discovered the truth in 2014, during a visit to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum: Herta died in SobibÓr, an extermination camp in Poland.

The opera concludes with the lost letter, as Rosenthal calls it. Dr. Schmidt—a character based on the letters’ translator—tells Freddy that during the refurbishment of the town synagogue, they found a cache of mail that was never sent. In this invented letter, Herta tells Erich that she and the town’s remaining Jewish families are being forced to leave, but she is grateful he was able to escape. “Your leaving was God’s gift,” she says, “Your living is my gift.” Knowing this, Erich is able to reconcile with his children before he dies.

Rosenthal trained as a classical pianist at the Manhattan School of Music and has composed piano concertos and music for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. But he is best known as a jazz pianist who won the 1988 Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz International Piano Competition and who has performed with jazz legends like Wynton Marsalis.

Musically, Dear Erich brings Rosenthal’s love of jazz and classical music together; Porgy and Bess was a loose model, he says. (Kurt Elling, AM’17, sang one of the pieces from Dear Erich during the Jazz Cruise, a jazz festival on a cruise ship, last year.) The scenes in Chicago where his father is courting his mother, Lili, are set against a background of jazz. “The decision to use a quintessentially American idiom is poignant,” wrote the reviewer for the New Yorker. “Erich falls in love to the strains of a Cole Porter–esque tune.” Like the lost letter, this too was invented: while his father enjoyed some American culture—Broadway musicals, Jack Benny—he was not a jazz fan.

Trying to get the jazz musicians and opera singers to work together smoothly was a challenge, Rosenthal discovered. In the operatic world, “there’s this flexibility to the pulse and the time,” Rosenthal says, while in jazz, “there’s this swing, beat, or groove.” The instrumentalists had to learn not to steamroll over the singers, who wanted to take time to add drama, while the singers learned to stick more closely to the beat.

Future performances include concert-like presentations at synagogues and Jewish centers, as well as a jazz concert of music from the opera in Copenhagen in June. Rosenthal hopes to perform the opera in Chicago someday. “It does feel like the University of Chicago itself is a big part of the story of Dear Erich,” he says. “I think it would be very meaningful.”