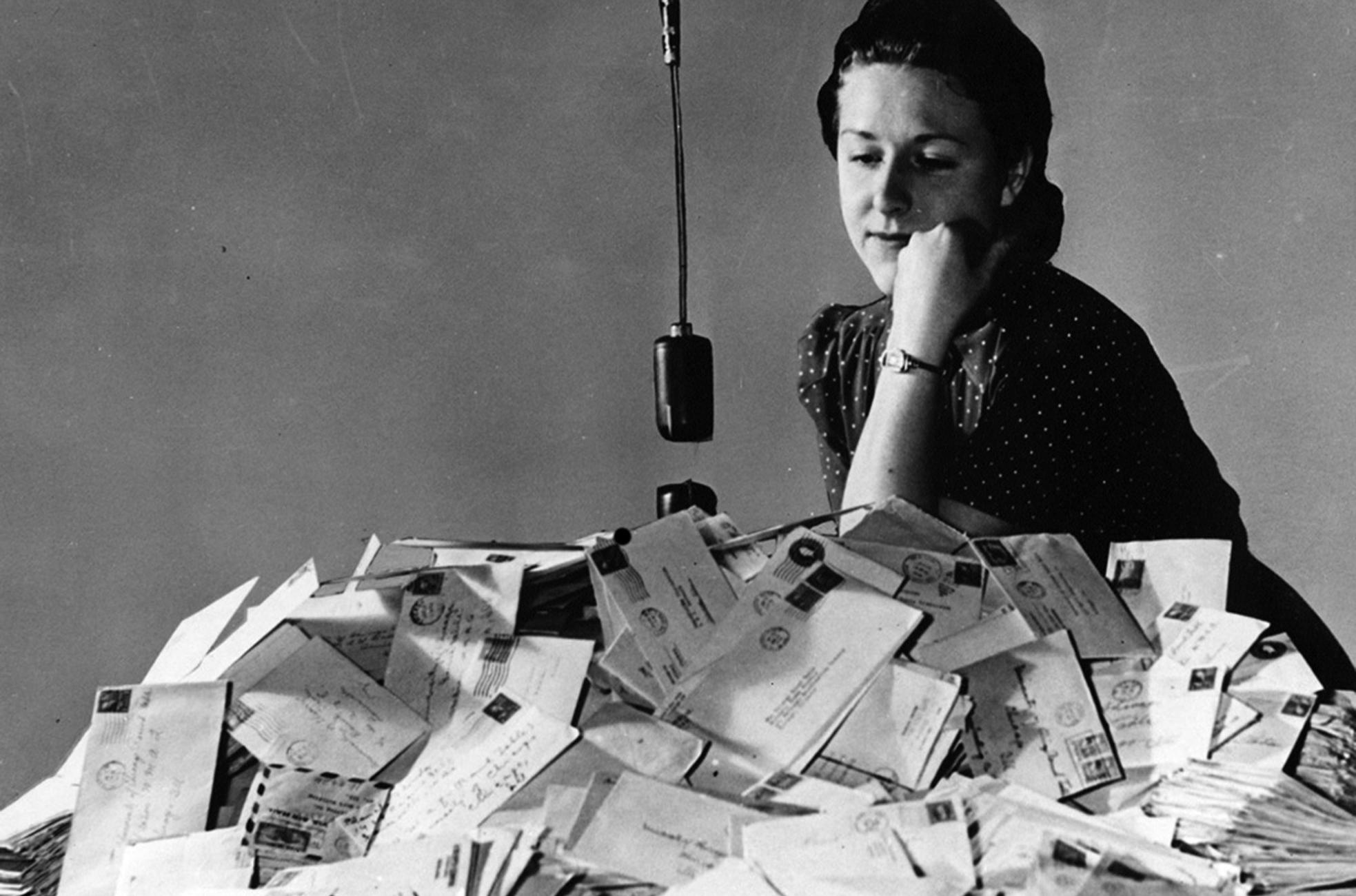

Listeners’ mail to the University of Chicago Round Table radio program, undated photo. (UChicago Photographic Archive, apf3-02383, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Your thoughts on crony capitalism, items found and kept, the math pirate, and more.

With cronies like these …

I am amused that Professor Luigi Zingales titles his course “Crony Capitalism.” The article (“Cronies with Benefits,” Fall/25) focuses on how cronyism distorts free markets, but it overlooks the irony that capitalism, in its original sense, is substantially absent from today’s economy. Canonical capitalism features a person or an institution that funds a venture in the expectation of sharing in the profits of the enterprise. This works when ownership is concentrated in a few hands. Today, however, company ownership is typically held by numerous smaller investors whose individual ability to demand a share of the profits is so dilute as to be nonexistent. Companies no longer feel obligated to distribute profits to shareholders. Rather they dispose of excess earnings by giving inflated compensation to the managerial class, who sit on each other’s boards of directors and approve salaries and perks for their counterparts that would make true capitalists blanch. There are your cronies!

Well-managed companies in the mid-20th century paid their executives 30 times the salary of a line worker and paid dividends to shareholders. Today, executives get many hundreds or thousands of times the compensation of line workers, and there is nothing left to distribute as dividends. Businesses are run more for the benefit of the executives than the ownership. A share of stock is no longer a capital investment to participate in the profits of a business, but a speculative gamble that somebody will be willing to pay you more for it at some time in the future. Even large investors, like so-called venture capitalists, intend to make money by selling their asset at a profit, not by participating in the proceeds of the business itself. By and large, “capitalists” who put up money to own shares of stock get nothing from the business operations, so why should Zingales (or any economist) characterize our economic system using the word capitalism?

Keith Backman, SB’69

Bedford, Massachusetts

Found and kept

You asked readers to let you know what they have held on to from life at UChicago (“Coastal Unshelving,” Editor’s Notes, Fall/25). There are a few things I simply cannot throw away, no matter how often I move homes and offices. They include my notes from Systems I, taught by Professor Marshall Sahlins with then–Assistant Professor Sharon Stephens, AB’74, AM’78, PhD’84, and other class notes from courses that have impacted my career and life in general.

One folder always stands out: the letters and small packages sent by my dissertation adviser, Professor Paul Friedrich. Once I had taken my job, thanks to him, at the US Naval Academy, he continued to reach out to me with small notes as well as entire volumes he expected to (and mostly did) publish. And my favorite: notes on the language development of and small arguments with his very young son, Nicky. He always took my input to his drafts seriously, which I am, to this day, embarrassed about, as I realize I had so much to learn—and still do. I miss his surprise letters in my mailbox since his passing.

Clementine Fujimura, AM’87, PhD’93

Annapolis, Maryland

I love your note and know well that feeling, however temporary, of having things sorted. When my mom sold our childhood home on Long Island a few years ago, going through the garage was one of the most emotionally exhausting things I have ever done. I only had a couple of days to go through it because it was in the lead-up to my wedding, so I didn’t sleep for three days.

I remember how strange it felt to encounter remnants of my past self—my baby clothes and toys, childhood drawings, mortifying middle school journals, a beautiful letter from a classmate who had since passed away, photos from when my parents were still married, ticket stubs and receipts, notes and tchotchkes from my first boyfriend whom I followed to UChicago, University Symphony Orchestra programs, essays, and a lot of books published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, my first real job after college.

It was a total emotional roller coaster, and purging most of that stuff was extremely difficult—it felt like letting go of the past. But someone in my current apartment building who is now clearing out her parents’ apartment reminded me that whatever was in those boxes is actually in “here”—she pointed to her heart. It’s part of you already and not necessary to tote around forever. That brought me a lot of comfort.

Indeed, I have held on to so much of my life from UChicago, especially, that I returned in the summer of 2023 to get married at Bond Chapel. My five bridesmaids were all friends from UChicago, and many more alums were in attendance. I love being a part of the alumni community, and I love going back to visit campus every opportunity I get.

Amanda (Hartman) Ryan, AB’13

Brooklyn, New York

I’m avoiding using numbers when I think of my upcoming reunion with the College Class of 1986 crew next year. But my flotsam and jetsam from the U of C includes the following.

Reflecting my ultimate path to owning several restaurants:

- An ashtray from the Berghoff

- Assorted Harold’s Chicken Shack logo items

- Matchbooks from Greek Islands and Second City

- A turquoise tiki-head glass from Cirals’ House of Tiki

Reflecting the impact of Hanna Holborn Gray:

- Thermal undies with “Hannah Say Nerk” on them

- My diploma additionally signed on graduation day by the deans, HHG, and the waiter from lunch

Reflecting life in the Shoreland and the College:

- My Compton House softball jersey

- A few tuition bills

- Polaroids from graduation day

Daria Lamb, AB’86

Mill Neck, New York

I live in a Manhattan apartment with three kids, so I don’t have space to hold on to much. However, I’ve still got the course catalog for each year I attended the University, and a pair of already-old-when-given-to-me U of C cross-country shorts the gym once kindly let me have when I forgot my mandatory shorts for gym one morning.

Elizabeth Bellis Wolfe, AB’03

New York

You asked what we held on to. I worked at the First National Bank of Chicago for 30 years beginning in 1965. I have every pay stub I received. Don’t ask why I kept them!

Sal Campagna, MBA’85

Lawrence, Michigan

Sally forth

I first met Paul Sally while working in the mathematics department as an undergraduate (“Classroom Legend,” Snapshots, Fall/25). At first he was just one of the professors in the department, but something was different about him. He was direct, engaging, and had an incredible sense of humor. Obviously he was a brilliant mathematician. But during my second year, I got to know him better when I taught in the Young Scholars Program and became a student in MATH 207-208-209.

Then, in the spring of 1995, everything changed. I had to take a leave of absence from school because of financial difficulties. On the very same day I submitted the paperwork to take a leave of absence, Dr. Sally lost his first leg due to complications from diabetes. A week later he called and asked me to visit him at his apartment so we could talk.

When I arrived, he was watching college basketball. It was March, after all. As the game wrapped up, he turned to me and said, “Hey, we need to get something out of the way first. Do you want to see my stump?” Before I could reply, he unwrapped his bandage and revealed where his leg had been amputated. “It’s supposed to harden up so I can use a prosthetic,” he said, “but it’s still pretty mushy. What do you think?” That was Dr. Sally: direct, engaging, and funny.

Then he told me he wanted me to be his personal assistant—“since I had so much free time, after all.” He needed help getting to rehabilitation appointments and meetings, and with running his education programs. For the next year I was on call for him, day and night. Whenever he attended a meeting, I came along, often participating even though I didn’t yet have a degree. He made sure I had a seat at the table, even when I hadn’t earned one yet.

Words cannot express the gratitude that I have for Dr. Sally. There is no way I could have completed my degree without his mentorship and generosity. I learned so much in that year with him, and some of it even concerned mathematics.

Now, as a teacher, I often tell my students stories about the “math pirate,” as he was affectionately known. Through those stories, I try to pass on the lessons he taught me. Life is not about how much you know, but the effect that you have on the lives of others.

Mike Kennedy, SB’96

Naperville, Illinois

I recall Paul Sally from the early to mid-1980s.

He coached the participants of the annual Putnam Mathematical Competition diligently and very effectively. Undergraduates would meet with him in the first floor auditorium lecture hall of Eckhart Hall to drill and strategize. Mr. Sally helped the U of C team achieve excellent results.

Mr. Sally taught a Friday late-afternoon course in one of the east classrooms on the second floor of Eckhart. One Friday the fraternities across the street on University Avenue started their weekend celebrations early. The music blared loudly from the speakers, which were perched in the windows pointing directly at Eckhart. Mr. Sally was visibly annoyed, paused his lecture, and left the classroom. He returned 10 minutes later having achieved a ceasefire to the loud music and clutching a large glass of freshly pulled keg beer.

Mr. Sally sometimes smoked during class. One time he confused the chalk with his cigarette and took a drag from the piece of white chalk. He didn’t realize his mistake until he tried to write on the board with the lit cigarette.

Ian McCutcheon, AB’91

Chicago

I was a student in the very first Moore method calculus class in fall 2004, which was taught by Paul Sally and Diane Herrmann, SM’76, PhD’88. I believe it was Mr. Sally who called it “Public Humiliation Calculus.” It was an apt name, because many of my clearer memories are of times when I was trying to prove something on the blackboard and got it wrong. That said, I might not have been a math major if it weren’t for that class. I can share a mix of some episodes and some of his more memorable quirks.

First, yes, he had a great distaste for cell phones. Over the Summer Quarter he was an instructor in the program where undergraduates taught Chicago Public Schools teachers, SESAME (Seminars for Endorsement of Science and Mathematics Educators). His rules about phones in the classroom even extended to these teachers. He was a bit more lenient; instead of destroying their phones, he confiscated them until the end of the day. Even other teachers had to follow the rules. Further, and I’m not sure I trust my memory here, I believe that if you answered a text during one of his lectures and he caught you, the punishment was that he (or a TA) would read the text or email to the class.

To my memory he never used the term math, always mathematics.

He had a habit of licking chalk before writing with it on the blackboard.

Since he was a basketball fan (and played in college, if memory serves), he would occasionally reward good questions, observations, or proofs by saying they were worth two or three points. These didn’t translate into real points for grades, sadly.

For a long time, he taught the notoriously difficult Honors Analysis in Rn class (MATH 207-208-209). I didn’t take the class, but while I was there, he assigned a proof equivalent to the Riemann hypothesis as an extra-credit problem. The thing was, he didn’t tell the students that it was equivalent to the Riemann hypothesis (and therefore likely impossible for them to prove), and so some of them spent a lot of time trying to get it.

He was the only person I’ve ever known to say “Bingo bango.” When walking through a particularly elegant proof, he’d say “Bingo bango!” at the end to signify that it was complete. This one has stuck with me all these years and is something I occasionally say myself.

Brian Taylor, AB’08, SM’18

Rockville, Maryland

Viewpoint viewpoint

I attended the taping of Ted Koppel’s Viewpoint TV show that was held in Mandel Hall (“Campus Views,” Snapshots, Fall/25). Your recent photo captures the back of my head quite nicely (white shirt, just to the left of the standing audience member). As the cartoonist for The Chicago Maroon at the time, I had the additional honor of sketching Ted as his doppelgänger Alfred E. Neuman (of MAD Magazine fame) for the issue after the taping.

Keith Horvath, AB’83, MD’87

Charleston, South Carolina

Regarding the Reg

How did the Reg change my time on campus (“Day of Reg-oning,” Snapshots, Fall/25)? A lot! Then and later.

As an undergrad in 1968 I enjoyed skulking about on the Regenstein’s construction site—a practice I had perfected while growing up in the mid-century housing developments in Libertyville, Illinois, and then continued in the steam tunnels between Rockefeller Chapel and International House.

I came upon a set of the Regenstein construction documents on a worktable and absolutely marveled at their beauty and precision. I noted the initials “WT” in the “Drawn By” box on the Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM) sheets and filed that information away for later use, as it turned out.

I soon left the U of C for two years of swing shift work at US Steel South Works, doing wet chemistry assays of steel coming out of electric furnace No. 2. My second year chem class definitely paid off there.

Back at the U of C for my final year in 1971, I again enjoyed skulking around in the Regenstein, by then completed and opened. Books of guitar music and archaeological history drawings were my favorites in its collections.

After graduating from the U of C and getting another degree in architecture, I walked into SOM and met Walter Netsch and started working for him. And I met the mysterious “WT”—Wayne Tjaden—who had made those lovely drawings a decade earlier. I say “mysterious” because Walter loved Wayne’s work so much that he let Wayne take occasional leaves of absence from SOM to go repair organs across the Midwest.

A high point of my work in Walter’s studio was visiting Algeria and presenting our designs for the state university system.

Anders Nereim, AB’71

Chicago

Cover story

I want to thank you for the cover of a previous issue featuring 57th Street Books (Summer/25). I managed the Seminary Co-op’s stores for many years, and the illustration got me thinking about the store and brought the usual flood of memories. We opened on 57th Street on Saturday, October 22, 1983. The spring and summer leading up to the opening were exciting and full of challenges but definitely worth the effort.

I will limit the flood of memories to a reasonable number or the rabbit hole will be unending. Devereaux Bowly, LAB’60, the owner of the building on the southwest corner of 57th and Kimbark, called me in early 1983 and asked if the Co-op would be interested in opening a second store in the English basement of his building. I met him in the space and said yes immediately, with the proviso that the Co-op’s board would have to agree and a lot of work would have to be done first on planning and financing.

Many people offered valuable advice and gave suggestions. Bob Strang, a Lab School teacher and board member, was enthusiastic, as were many customers. Ted Cohen, AB’62; Rebecca Janowitz, LAB’70, AM’08, MPP’08; her sister Naomi Janowitz, LAB’72, AM’78, PhD’84; and countless others were encouraging. The Hyde Park Bank, on the basis of a one-page proposal and a 15-minute meeting with its president, agreed to extend a two-year loan of (I think) $150,000.

Dev Bowly would pay for everything involved in getting the bare space ready: all new electric, relocation of heating pipes, etc. We would be responsible for build-out, inventory, and everything else. The board’s main questions were around how to justify the enormous increase in operating expenses a second store would bring.

We on staff said that the new store would be complementary to the old location but aimed at a broader market: a general interest store in a university community aiming to be a neighborhood bookstore for an extraordinary neighborhood and, more broadly, for the South Side of Chicago. We were pretty confident that if we could manage to be that while maintaining the original store, we could attract customers from all of Chicagoland, from around the country, and indeed from around the world.

The store has served hundreds of thousands of customers, helped generations of kids develop a love of reading, hosted thousands of author events, and, I hope, been a fine neighborhood fixture. Thanks again for the cover illustration.

Jack Cella, EX’73

Duluth, Minnesota

Green cuisine

The last issue of the Magazine invited reminiscences about Green Hall (“Work Studies,” Snapshots, Fall/25). I lived there for two academic years, 1961–63.

At that time, no meals were served to residents. I and my fellow students chose Green because we were allowed to cook there for ourselves. There were four stoves and four refrigerators, each shared by 10 girls. We each had a half locker in which to keep our pots and pans, eating utensils, and supplies not needing refrigeration. It was a wonderful communal experience and a great way to save money. Five dollars a week covered all my meals, and I am still very close friends with one of my co-diners. I got married after graduation. My mother donated the money she had saved on my food toward our honeymoon.

We each were expected to clean the oven and broiler of our stove in rotation. One girl who lived on a low floor volunteered to step in when the duty had not been performed by a certain time of the evening. The missing girl had to pay her a set amount. Both of us who lived on the fifth floor—it was a walk-up—and forgot to do the cleaning before going up to our rooms were the most common guilty parties.

The dining room still existed, complete with furniture. I decided that as a senior I should demonstrate my maturity and sophistication by inviting a faculty member to dinner. My art history professor accepted the invitation. I got a recipe for beef stroganoff. Unfortunately, I added the sour cream too early in the process and it separated. I hoped that vigorous stirring would camouflage my mistake. Fortunately, my professor was very gracious and seemed to enjoy his meal.

Nada Logan Stotland, AB’63, MD’67

Chicago

Orfield’s field

I was so moved when I saw the picture of Gary Orfield, AM’65, PhD’68, and some of his crew from 1988 in the Summer/25 issue (“Civil Rights Scholar,” Snapshots). Gary was a pivotal figure in my U of C journey.

I had the enormous honor of being a student researcher on a project he led during my junior year (1983). The project was “Latinos in Metropolitan Chicago: A Study of Housing and Employment, a Report to the Latino Institute.”

I remember Gary’s calm, supportive leadership and his sense of humor. He was the first professor I recall who was a social activist, and he opened my eyes to the issue of justice behind all the sociological theory I’d been consuming up until that point.

Part of my role was to run around downtown and gather up paper versions of 1980 Census data reports and then manually calculate percentages for unemployment, income, and housing for the Latino population.

It was tedious work, but I felt part of a dynamic team for the first time—so much of the U of C undergrad experience in the “un-fun ’80s” felt so solitary. And Gary was a joy. On the day we released the report to the Latino Institute, he rented an old car—I remember it as a classic Cadillac (still flashy despite many years and miles)—and it seemed that seven people piled in and rumbled up Lake Shore Drive with Gary at the wheel. That’s how I’ll always remember him, bringing meaningful scholarship into real situations and taking generations of students along for the ride.

That experience lit a fire in me to do more than learn theory (and pore over census records)—and I decided I was going to become a social worker.

The rest is history. I’ve had a nearly 40-year career in human services, from direct service to advocacy to research to training to communications. Gary was a moral compass who helped me find my way.

Sheila Black Haennicke, AB’84, AM’86

Oak Park, Illinois

MAB memories

For 50 years the Major Activities Board has fought to make sure that UChicago is not a place where fun goes to die (“Totally Major,” Snapshots, Fall/25). I want to reach out to the University community to ask for its assistance in commemorating the 50th anniversary of MAB by creating a more definitive archive of photos, memories, and more.

My research (aided by the Ask a Librarian service at the Reg and a review of Chicago Maroon articles) shows that in 1975 UChicago created the Major Activities Board—providing a one-time grant to improve social life on campus in the academic year 1975–76. It looks like the first MAB show was October 11, 1975, and featured folk artists Livingston Taylor and Bryan Bowers at Mandel Hall. The first board, led by chairperson Aaron Filler, AB’77, AM’79, MD’86, was successful in passing a referendum to provide financial support for MAB. Over 50 years there have been hundreds of MAB alumni and probably well over 100,000 event attendees.

During my years on MAB (1978–82) we were fortunate to be able to produce 10-plus concerts per year, bringing artists like U2; the B-52s; the Ramones; King Crimson; Pat Metheny; Al Di Meola, Paco de Lucía, and John McLaughlin; Tom Waits; Chuck Berry; Henny Youngman; Arlo Guthrie; John Prine; and many more to campus. Future boards brought acts including Sonic Youth, Jonathan Richman, and Youssou N’Dour, and recent shows have included Megan Thee Stallion, Phoebe Bridgers, and Carly Rae Jepsen. Unfortunately, there appears to be no definitive list of shows or any one place where MAB archives reside.

If you were a board member or attended a MAB show and have photos and/or memories to share, or if you would like to assist in this project, it would be great to hear from you. Please reach out by email to uchicagomab50@gmail.com, and we will do our best to commemorate MAB’s 50th and create institutional memory. Thank you.

Bart A. Lazar, AB’82

Chicago

The University of Chicago Magazine welcomes letters about its contents or about the life of the University. Letters for publication must be signed and may be edited for space, clarity, civility, and style. To provide a range of views and voices, we ask letter writers to limit themselves to 300 words or fewer. Write: Editor, The University of Chicago Magazine, 5235 South Harper Court, Chicago, IL 60615. Or email: uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu.