Planetary scientists fact-check The Martian.

An aerial shot follows fictional astronaut Mark Watney driving a rover across the rocky surface of Mars, dust devils swirling across the landscape. It’s a striking scene, but is director Ridley Scott’s depiction of the red planet accurate?

On a January Saturday, after a screening of the Oscar-nominated film The Martian, a panel of UChicago planetary scientists weighed in on its scientific accuracy. The film’s basic premise: the astronauts of Ares 3 are forced by a violent dust storm to evacuate, leaving behind Watney, presumed dead. He survives but has no way to contact NASA, and the next manned mission is four years away. So Watney, a UChicago alumnus, must use his science acumen to get home. (The character is played by Matt Damon, who by one estimate has been rescued throughout his acting career to the tune of $900 billion.)

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"3272","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"360","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"500"}}]] Doc Films and Science on the Screen—a series sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research and for National Laboratories—hosted a screening of The Martian, followed by a panel of Mars experts. Left to right: Andrew Davis, Thanasis Economou, Mohit Melwani Daswani, and Edwin Kite. (Photography by Lloyd DeGrane)

The screening—put on by Doc Films and Science on the Screen—inspired a spirited discussion of reality and speculation from the UChicago scientists. The panel featured Thanasis Economou, a senior scientist in the Enrico Fermi Institute who has worked with Mars spacecraft since the 1970s; Edwin Kite, an assistant professor in geophysical sciences who studies Martian climate evolution; and Mohit Melwani Daswani, a postdoctoral scholar in geophysical sciences who analyzes Martian meteorites found on Earth. The Department of Geophysical Sciences chair, Andrew Davis, moderated.

The big dust-up

The entire plot of The Martian hinges on one controversial detail: does Mars have dust storms powerful enough to force evacuation? “The atmospheric pressure on Mars is about one hundredth of Earth’s,” said Kite, “so wind would have to be going very fast indeed to tip a 20-ton Mars ascent vehicle.” In other words, the wind on Mars can’t create the mayhem depicted in the film, although it can cause problems with robotic parachute landings.

Mars’s thin atmosphere can support dust storms that cover the entire planet, but they take far longer to dissipate than they did in the film. Economou told the story of the Mariner 9 orbiter, which arrived in 1971 to find a global dust storm; it took months to settle. The Martian storm ended after a day. The dust devils—small, weak, dust-filled tornados—are real, however, and have been recorded.

Climate control

The Martian shows Watney experiencing relatively comfortable temperatures outside in daytime but nearly freezing to death after dark. The experts said this temperature range is realistic: because Mars’s atmosphere is so thin, the surface can heat up during the day, and that heat efficiently escapes at night. The planet wasn’t always this way, said Davis. Chemical evidence (the ratio of nitrogen isotopes) from Martian meteorites and atmospheric measurements suggests that Mars once had a thicker atmosphere, and scientists have offered a few hypotheses on why it was lost. Perhaps the “young sun had a stronger solar wind and more intense UV, and that stripped the atmosphere away,” said Kite, or “the thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere was turned into carbonate rocks.”

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"3273","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"284","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"500"}}]] Matt Damon portrays stranded astronaut Mark Watney in The Martian. (Photography by Aidan Monaghan, courtesy Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation)

One aspect of Martian atmosphere not depicted is its seasonal carbon dioxide cycle. “Every winter about a quarter of the mass of Mars’s atmosphere collapses as dry ice in the polar regions,” said Kite. Watney wasn’t far from the polar caps and might have experienced the atmospheric changes. The filmmakers also failed to account for radiation exposure. Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field help shield us, but on Mars, said Daswani, “the astronauts were being constantly rained on by solar radiation and cosmic rays.”

Soiled soil

Would a stranded astronaut be able to grow potatoes in Martian soil and human waste, as Watney did? Probably not, said Daswani. “There is nitrogen in the soil but perhaps not enough to cultivate potatoes.” The soil would also need more phosphorus, Economou noted. Martian soil does contain trace nutrients, and a 2014 study on Mars and moon soil simulants showed select plants could grow and survive for 50 days.

An audience member asked if Martian dirt could sustain any life for extended periods. It “depends on what kind of life you are,” said Kite. The robotic missions have detected high levels of perchlorate, a salt poisonous to humans, on Mars. But some microbes on Earth feed off perchlorates; Mars may be—or might once have been—hospitable to microorganisms.

Life as we know it requires water, and Martian meteorites found on Earth show past water activity. The meteorites, Daswani said, were “altered by water on Mars before they were ejected. We can tell a lot about the geological history of Mars from these rocks.” So Mars at one point could have supported life. In September 2015 NASA found evidence, based on hydrated perchlorates detected from orbit, of water currently flowing on Mars, but recent studies suggest it’s unlikely the planet supports life now.

Red rover

There would be no hope for Watney without access to decades’ worth of technology left on Mars. He makes use of fictional Ares 3 and 4 equipment but also real-life rovers, such as Pathfinder, for which Economou helped build an x-ray spectrometer.

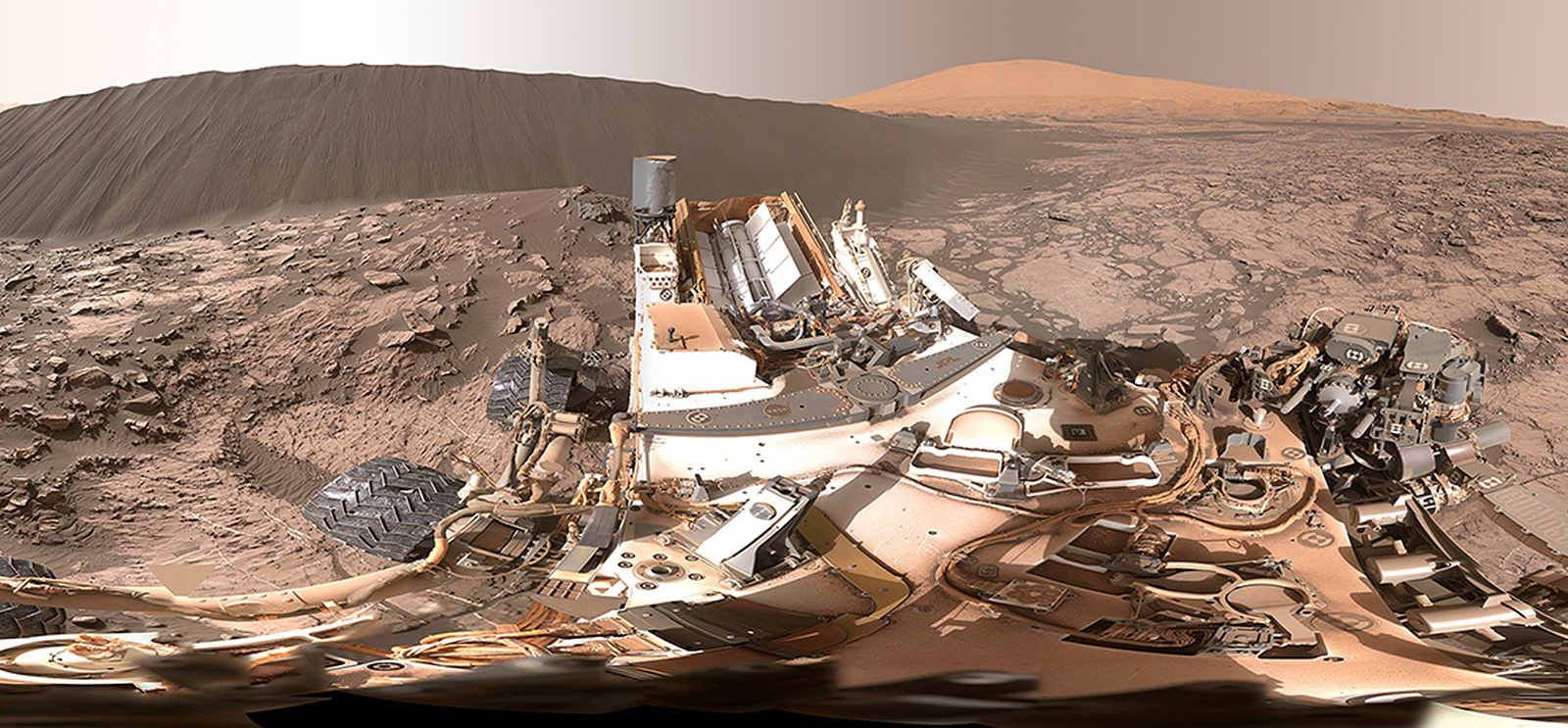

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"3271","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"587","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"500"}}]] Storms on Mars can interrupt rover activities by coating their solar panels in a thick layer of dust. Sometimes dust devils, which frequently form on the planet’s surface, spin over the rovers and clean the panels. These “cleaning events” have helped the Opportunity rover exceed its 90-day mission by 12 years. (Photos courtesy Thanasis Economou)

Although the film’s Watney is a botanist, in Andy Weir’s novel he is also an engineer, which helps explain why he is so comfortable building enclosed ecosystems and mashed-up rovers. Economou said that both the technology and the testing processes were portrayed realistically. He also noted that the Opportunity rover is like a robotic version of Watney—it was built for a 90-day mission and a 600-meter journey. “Now we’re on the 12th year, we’ve gone the distance of a marathon, and we’re still going.” (You can map Watney and NASA’s paths across Mars with the Mars Trek tool.)

The future

Neither the movie nor the book state when The Martian takes place, but Weir had a year in mind and wrote details accordingly. He planned for the astronauts to be on Mars around Thanksgiving—a reason for potatoes to be on board—and worked backwards. An internet sleuth crunched the numbers and determined that Ares 3 departed Earth in 2035. In reality, NASA hopes to send a manned mission to Mars by the 2030s. One obstacle, said Economou, is figuring out how to bring the Martian explorers back.

An audience member asked, Why send people at all? What can a manned mission do that a robotic mission can’t? A quick answer from Kite: “In the course of human exploration, a lot of science gets done.” To elaborate, Kite invoked the Fermi paradox. Considering the number of stars, the probable number of habitable planets, and the age of the universe, we should have found—or been found by—intelligent life by now. Enrico Fermi wondered, “Where is everybody?” Maybe a seemingly suitable planet for life isn’t truly habitable, or “maybe it’s that life just never gets a foothold,” said Kite. Both hypotheses can be tested on Mars.

Davis, who estimated a manned mission would cost $400 billion, reminded the audience that “China, which played an important role in this movie, has quite an active and accelerating space program. The first man on Mars might not be sent by NASA. Maybe he’s sent by some other country.” And maybe the first “manned” mission won’t be manned at all, said Kite. “The most recent NASA class for long duration flights,” he noted, “was half female.”