An architectural rendering of a staircase in Burton Judson Courts, built in 1931. (UChicago Photographic Archive, apf2-01398; inline illustrations by Shiloh Miller, Class of 2026)

On living in and out of the moment.

1

I came to Chicago three years ago. I liked it immediately. Every week I’d take the red line downtown and listen to the train chime and shudder. On warm days I’d try to do work on the quad and end up sitting sun-drunk on the grass, a closed book next to me, doing nothing but looking around at the world and its endless hours.

2

Above the doorway of Cobb Café, in the bowels of the oldest building on campus, written in cursive: “An exercise in nostalgia.” Lets you know what you’re in for. Cobb Café used to be called Mandala Coffee Shop, a name that phased out of the student body’s collective brain decades ago. It now lives on only in stranger, narrower places—newspaper archives, bygone legal records, the subconscious of long-graduated alumni.

3

My first time in Burton Judson, my old dorm, was not during move-in but on an admitted students’ weekend five months prior. The host student I was staying with lived in the University’s newest dorm, Woodlawn, but a text from her friend that night prompted a spontaneous trip to one of the study rooms on BJ’s second floor. What was to my host student an unremarkable walk to the neighboring dorm I perceived as a capital-J Journey, the kind that Odysseus might have made. I followed at her heels as we swept through labyrinthine halls, shadowy corners and staircases materializing and then vanishing beside me, and, as we emerged into the study space, I remember thinking that I couldn’t find my way out if I tried. A year later, after having lived in BJ for some time, familiarity had snuffed out mystery. I knew that the dark staircase led to the laundry room, that the shadowy corner housed a printer. But when I walked up the stairs to the study room, I could still somehow call to mind my impression of the place when it was wholly unfamiliar—mysterious, disorienting—and I’d get a strange kind of double vision, where I sensed the space as larger than it ever was.

4

Jai Yu, assistant professor of psychology, studies memory. He says: “You think about memory as if we are recording on tape all of our experience, and then replaying that section of the tape to recall that experience. But maybe that’s not how memory works. Maybe memory is more about you having an experience, deconstructing it into all of its components, and then somehow building it again based on those components.” The same neurons in the brain that fire when you have an experience fire again as you recollect it. “Almost as if you’re conjuring it up,” he says. The word conjure, with its connotations of magic and trickery, is apt. “Memory is not just a process of recollection; it’s also a process of construction,” Yu says.

5

In the winter I took a class on spiritual, psychedelic, and visionary writing. The class was in Midway Studios, a drafty Frankenstein of a building made from the merger of a brick barn, its additions, and a Victorian house. Our professor stood at the head of a concrete room, the light fading outside as the sun went down. “When you burn your hand on the stove,” she said, “you don’t think about the stove. You just feel incredible heat.” Some of the work we were reading, she proposed, was attempting something similar—to convey what something was like in immediate perception rather than in cognition.

6

My sister has memories so tender and delicate that she purposely doesn’t revisit them often, like paintings at museums hung behind a black shroud to keep them from being damaged by the light.

7

The “reminiscence bump” is the phenomenon of adults having a disproportionate amount of memories from their adolescence and early adulthood. There are a number of theories as to why this is. The cognitive account proposes that experiences at this time of life are often new, and new things are easier for the brain to remember. There’s also the narrative explanation, which is that the experiences you have when you’re young form the adult brain that looks back on them. As one psychology paper put it: “It is this time when an individual engages in activities and relationships that define who the person will finally become, and how they narrate the stories of their lives.”

8

Memory: the tottering plinth on which we balance our identity. I ask Yu how we are supposed to understand our sense of self when our memories molt into new shapes. “It still is you,” he says, “but you are just creating these narratives based on your own components of those experiences.” In this perspective, the self lies deeper than the memories that adorn it; what we lose defines us as much as what we keep.

9

A 1973 Maroon ad for Cap and Gown, a defunct yearbook, capitalizes on the fickleness of memory: “How much will you remember from this year? Are you taking pictures? Saving old calendars? Writing a diary? Would you like someone to record the happenings here for you?”

10

A disproportionate chunk of my college memories take place in Hallowed Grounds, the coffee shop on the second floor of the Reynolds Club. I had a professor who worked there in the 2010s who said he hadn’t been back since he was a student. Worried the memories might knock him flat. I was drawn to Hallowed at the closing of the day by an almost subconscious drive, like how a salmon returns to fresh water to die. I spent time at Hallowed long after the friends I used to see there began frequenting other venues. I’ve passed so many hours there that when I walk in, no particular emotion comes to the fore—my multitude of associations with the place have merged into a kind of soft-edged familiarity, like those blurred portraits made out of the average of a hundred faces.

11

And just like that, third year is over. There is more behind me than there is ahead. It’s a true (if trite) observation that college is life in miniature—we enter knowing next to nothing, and at the end we cross a threshold and can never go back. Most of my friends and I have one more year of college left—we are reckoning with the fact that we do not, in reality, have all that much time left to do the things we wanted or hoped or planned to do.

12

I have a friend who studied abroad for three consecutive quarters. I have a friend who isn’t studying abroad, because she is saving money to travel in her 30s. My friends have taken up Frisbee, guitar, Catholicism; have given up alcohol, triathlons, computer science. Have almost given up rowing but changed their minds. I know people who are applying to law school or joining the Peace Corps or moving to Italy to learn to make violins. A friend and I stay up late in the living room of my apartment, talking about how our world one year from now is more or less visible—thesis presentations, graduation photos, tulips in bloom—but where we’ll be two years from now is a mystery so total it’s almost comic. I have a friend who says that sometimes, despite being 21 and not yet a father, he thinks of his future kids and feels overwhelming pride.

13

Wilma Bainbridge, associate professor of psychology, studies memory. Bainbridge’s research focuses on what qualities of images make them more or less memorable. “It’s not just about you or your abilities or your strategies, but it’s the images themselves that have power over you,” she says.

14

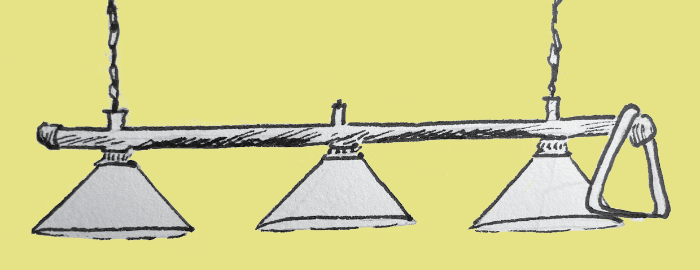

I don’t play much anymore, but I remember that pool at Hallowed was a kind of dance. It was close quarters. You’d have to look behind you to make sure you didn’t hit people studying at neighboring tables with the cue. I remember circling around a game with one or two or three friends, everything in constant motion, picking up coffees put down on the table’s lip, the triangle dangling not from the hook below the table but from the swinging light above it. The balls were chipped, and the felt was peeling, and the tables were so skewed that the balls would settle on one side. This was not really important. Like any game, pool at Hallowed was primarily a social activity, just another register to access the ancient human dynamics of friendship and love and revenge. I remember a few historic shots (one time the cue ball bounced up and rolled along the rim of the table, almost escaping, before clopping back down) but mostly I remember the friends I’ve played with, and the way we used to move.

15

My friends and I have a way of getting through days when everything feels like a slog, which is to pretend that we have died and asked God to let us spend just one more day on earth laden with grocery bags and essays.

16

I was talking to an alum who went to college 50 years before I was born. He mentioned the half-floors in BJ: regular stairwell landings with a few dorm rooms in a smaller hall. So you could live on floor 2, but also on floor 2.5. I realized that I had forgotten about them. The floors that I walked past every day for two years. It is baffling to me that aspects so essential to the daily mechanics or texture of a life—schedules, shoes, the path of light shifting across the wall in the mornings—are forgotten so easily. Even later in life, after our routines and spaces settle, I think if we were to go back just two or three years, we would feel as disoriented as an actor dropped onto an unfamiliar set. The costumes, the props—all different—all the characters showing up with forgotten hairstyles and habits, all the little things changed, down to the brand of soap in the bathroom.

17

My favorite spot in Hallowed is the cushioned benches next to the windows that look down at the first floor of the Reynolds Club, where the University seal is. I curl up there like a cat. From this vantage point I can see both the whole coffee shop and the people milling around downstairs, which feels like a kind of omniscience. It took me a year to learn that the benches doubled as a lost-and-found chest, that I was sitting on top of forgotten items.

18

“There’s no known capacity limit to our longer-term memories,” Bainbridge says. “It’s not like you run out of space to remember songs. But at the same time, there are clear limits, like, ‘Wow, I can’t even remember what I had for dinner last Thursday.’”

19

One of my most distinct memories from my time in BJ was nothing outwardly significant—finals had ended, and I was bringing a friend a plant that she’d offered to take care of over break. A song was playing from somewhere deep in the building. I knocked on her door, cradling the plant in my other arm, and in the moments before she answered a liminal feeling rose up around me. Most everyone had left for vacation, and the whole dorm was suffused with the uncanny stillness of abandonment, and a song—“California Dreaming,” I could tell now—was playing, muffled, from someone else’s room. For a moment the song was the axis the whole world turned on.

20

Last quarter I had a professor who had been studying Goethe for twice as long as I’ve been alive. One cold morning he peered out at our faces and said, “Years later you’ll feel nostalgic for Chicago. For the winter. You’ll miss it.”

21

I liked living in BJ. I liked how old it was, I liked that I had to use a real key. When I moved out for good, I had the vague intention of commemorating my time there by hiding a note in my room to be found by its future resident. But in the dust and disorder of move-out day, the sound of bins on wheeled pallets rattling across the courtyard, borrowed cars idling on the curb, I forgot. And then I was standing outside BJ in the grass with my bags, my key turned in to the front desk, and that was that. Behind me and up the stairs was my old room, doors and windows closed, the dust already settling back on the desk. I’d left it as bare as it was when I arrived, nothing to prove I was there but the chipped-off paint on the ceiling from when I taped up balloons for my twentieth birthday party.

22

No matter how meticulously I document the minutiae of experience, I know there are things that have been lost. There are memories that run like underground rivers in my subconscious, intricate and imperceptible. But even for the ones that stick around, there is only so much that writing can do. For a long time I worried about the damaging power of putting something into words. I believed that the story we told ourselves about any given experience was told in lieu of its reality. But when I look at an old journal entry and unearth a forgotten crop of memories, when I realize the reality of a certain month or season diverged wildly from my impression of it, or when, despite my records, I cannot place with accuracy when small habits or arrangements or events began or ended, I feel that it is time to throw up my hands. I can write my years here down in journals, logs, calendars, try to figure out what it all meant, but at the end of the day, all I can say with any certainty is that it happened.

23

“There’s a lot of work to suggest that as time goes by, your autobiographical experiences lose detail but gain a ‘gist’,” Yu says. “You’re seeing this transformation of what you remember into more of the essence of those experiences, rather than the minute details.”

24

Three years ago I knew nothing here. Now I have memories in a hundred rooms.