After more than a century, Mitchell Tower gets a new set of bells.

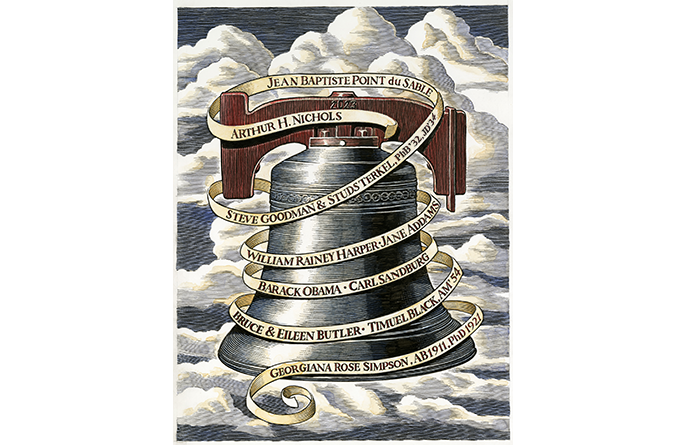

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the heavyweight, comes in at 2,042 pounds. Meanwhile Georgiana Rose Simpson, AB 1911, AM’20, PhD’21, weighs 513 pounds, Jane Addams a mere 499.

The 10 giant bronze bells, dedicated in August, were named in honor of notable people with ties to the University, to the city of Chicago, or to bell ringing. Cast in Loughborough, at England’s only remaining major bell foundry, the bells were installed in the Reynolds Club’s Mitchell Tower this past summer.

The bells were a gift from Christian J. Haller, AM’72, and Helen D. Haller, who also donated funds for their upkeep and for a change ringing program for students (learn more about the Hallers). At the Hutchinson Court ceremony, Chris Haller said he fell in love with change ringing as a UChicago student in the early ’70s: “Bell ringing is great for the mind.” Since then the Hallers have rung bells in thousands of towers worldwide.

Change ringing is most common in England, where it’s been practiced for centuries. Bell towers typically have six to 10 large bells, each rung by one person pulling a rope. Change ringing produces patterns of sound, rather than recognizable melodies (think of news coverage of weddings and births in the British royal family). It’s called change ringing because the bells are rung in different sequences, and those sequences change.

The Guild of Change Ringers at UChicago, which includes students, alumni, and community members, meets twice a week to practice. Bell ringing requires training and can be dangerous: “The worst-case scenario,” says Tom Farthing, tower captain, is that “the rope could wrap around a limb and pull you up to the ceiling.” (Farthing’s Dickensian-sounding name is so perfect for his hobby, he’s sometimes asked if it’s a pseudonym.)

Bell ringers can’t actually see the bells; in Mitchell Tower, as elsewhere, the bells hang above a ceiling. Instead, the ringers look at each other, so they can work together as a group. Natalie Nitsch, AB’23, a Divinity School master’s student and guild member, says when she’s ringing, she enters a “numerical flow state.”

During practices, the bells are silenced. The bells ring “open” (audible to the neighborhood) for an hour each month. They are also rung open on special occasions, such as the coronation of Britain’s King Charles III this past May. During the dedication ceremony for the new bells, guild member and mathematics PhD candidate Isabella Scott, SM’18, SM’20, fondly recalled participating in the celebratory bell ringing after their own graduation.

Change ringing is a fairly esoteric pursuit in the United States. There are just 42 bell towers in the entire country. Illinois has one other bell tower, in the Chicago suburb of Riverside. The next-closest tower is in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Farthing says; after that, it’s Pittsburgh.

Mitchell Tower’s original bells were dedicated in 1908 in honor of Alice Freeman Palmer, the first dean of women in the graduate schools. Each of the 10 bells is inscribed with a biblical phrase said to befit her, such as “A gracious woman retaining honor,” “Rooted and grounded in love,” and, remarkably, “Making the lame to walk, the blind to see.”

This past August the Palmer bells were temporarily taken out of the tower (the bell inscribed “In God’s law meditating day and night” sat in the middle of 57th Street for days) and then reinstalled above the new ones. According to Farthing, the Palmer bells will no longer be hand rung in the traditional way. Instead, they will be controlled by a computer.