Sam Pluta during a 2014 performance with trumpet player Peter Evans. (Video still courtesy Sam Pluta)

For Sam Pluta, music is the ultimate computer game.

Music is information, says Sam Pluta. A series of signals your brain receives and interprets. Pluta, an assistant professor in the Department of Music and director of the Chicago Integrated Media Experimental Studio, is interested in what happens when you “add information” to that signal. In his Humanities Day lecture, “Information as Beauty in Musical Software Design,” Pluta discussed the musical performance software he created 14 years ago and has used ever since. With his software, the Live Modular Instrument (LMI), Pluta can delay sounds, filter out one or more areas of the sound spectrum, and use synthesizer effects that change the sound itself. It’s a bit like Auto-Tune on steroids.

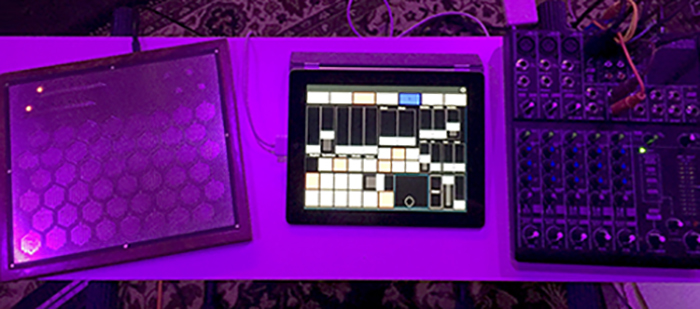

Pluta runs LMI on an iPad and a touchpad called a manta. The manta is made of wood and metal and looks decidedly analogue; maybe like some kind of steampunk video game console. He needs an interface, of course, and a sound mixer to protect audiences from the occasional unintended ear-piercing shriek. Hit the wrong note on a piano during a jazz improvisation and it sounds inelegant; hit the wrong note when you’re changing the noise spectrum and you could actually cause pain. “So much of the brain is taken up by just making sure you’re not hurting people,” Pluta said. His influences include not only musicians—Roscoe Mitchell, Don Buchla, Anthony Braxton—but also Edward Tufte, a pioneer in the field of data visualization. Like Tufte, he’s interested in the way different types of information work together to present a whole picture. After playing a series of recordings of Bach’s Sarabande from Cello Suite No. 2—run through an increasingly complex set of effects—to demonstrate, Pluta took his process apart for an audience that included a healthy number of computer programmers and musicians. LMI’s nonlinear nature allows Pluta to get into a flow state, to move with the music as any musician would, and not have to stare at a screen constantly. “The challenge I put forth for myself,” he said, “is building a modular system where I have many, many approaches.” He likened his performance to a scene in Iron Man where Iron Man is inside the suit, frantically punching buttons, then moves to another array of buttons to do something entirely different. Pluta’s performances range from heavily rehearsed to completely improvised.

During the talk he played a video of one of his performances with trumpet player Peter Evans. Run through Pluta’s effects, Evans’s trumpet sometimes sounded like a trumpet. At other times it sounded like spitting, an old-fashioned propeller plane, squeals, pops, gongs, an alarm clock beeping, train whistles, a human voice, static, and tape hiss. At other times it sounded like nothing at all, even though Evans was clearly playing. The performance was utterly watchable. It also prompted serious contemplation of the dimensions of a single musical note, how we listen to music, why we listen to music, and what music is. “Sometimes the sounds we make are described as violent or aggressive,” Pluta said, “and they are.” But what is also evident in the video is that the musicians are filled with what he calls the “utter joy of playing music together.”