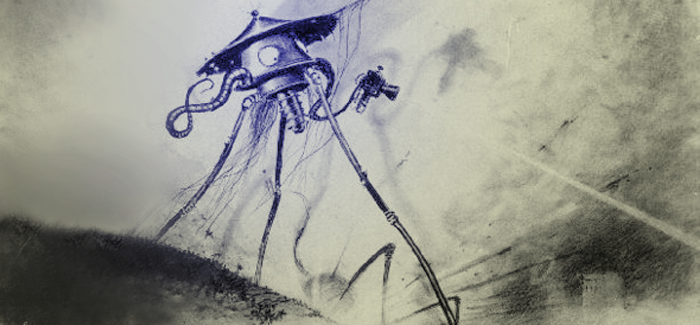

Artwork by Brazilian artist Henrique Alvim Corréa from the 1906 Belgian edition of the War of the Worlds. {PD}

Tweeting Orson Welles’s famous radio drama on its 75th anniversary.

On October 30, 1938, millions of Americans turned their dials to CBS’s accounts of a nation in flames and under attack by Martians, and they didn’t take it well. The New York Times reported a “wave of mass hysteria" for which “a score of adults required medical treatment” the next morning, and CBS received hundreds of calls and thousands of letters complaining that they had been hoodwinked when the world went on turning.

Seventy-five years later, during an anniversary rebroadcast of Orson Welles’s radio drama War of the Worlds, listeners weren’t panicking. They were celebrating.

In the months leading up to the anniversary of what he calls “one of the great works of art of the 20th century,” humanities fellow Neil Verma, AM’04, PhD’08, presented a slideshow about War of the Worlds at Doc Films and posted about the play on the media studies blog Antenna. For the anniversary itself, though, Verma and his fellow cultural historians nationwide had something special planned. “Rather than try to turn this into a truly analytical enterprise,” says Verma, a cultural historian, “we wanted a new kind of listening experience.”

Verma, Binghamton University’s Jennifer Stover-Ackerman, and several others decided to use the hashtag #WOTW75 to organize listening. At eight o’clock EST sharp, a couple hundred participants either pressed play on an online recording or tuned into the Binghamton, New York, local radio station WHRW’s replay of the broadcast. The tweets started flying. By the end of the broadcast, Verma and his colleagues had more than 1,700 tweets, and #WOTW75 was trending.

The tweets ranged wildly, from humorous riffs on the play (“Look, if they want New Jersey, let them have it. #letNJburn #WOTW75,” from @Hauske) to analysis as serious as 140 characters would allow (“#WOTW75 the tension between immediacy and distance, faith in technology/science and self vs god, fascinating mediated reality! Heat rays!” from @Brarian). One woman tweeted haikus quoting the play. A trimmed-down collection of the tweets is due to be published as a book by Velvet Lightrap next year.

“When the War of the Worlds broadcast first happened, it was one of the first instances of listener response in real time,” says Verma. “We know more about the public response to this play than just about any other play aired, so we wanted to mirror that in this exercise.”

Verma contributed plenty to that exercise himself, as he listened at home to the WHRW broadcast. His favorite anecdote from the original War of the Worlds panic, he says, is actor John Barrymore sending out his beloved dogs for a last moment of freedom before the end of the world. So Verma tweeted a picture of Barrymore with his dogs, as well as the sort of insights that come with having listened to the play “dozens and dozens of times,” he says. For instance, he pointed out its only reference to a woman and catalogued its lighthouse imagery.

There are two major schools of thought on War of the Worlds: that the broadcast’s resulting panic says something about the gullibility of listeners in the 1930s, and that the panic isn’t quite what it’s trumped up to be. Verma refuses to come down on either side of truth or myth.

“I prefer to take it as an allegory,” says Verma, whose book Theater of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama (University of Chicgao Press, 2012), tackles some 6,000 such plays. “I feel like War of the Worlds is something that we should do a better job of appreciating, rather than obsessing about the panic. It has an amazing amount of smart sound decisions about pauses, delays, silences, and characterization, and the depth of sound.”

There’s plenty to unpack about War of the Worlds: its contentious public reaction, its compelling realism, and its periodicity, for example. Verma is particularly fond of the existential angst of its second act, during which professor Richard Pearson delivers a long monologue as he watches the Martians’ short-lived reign on Earth come to an end.

“You could say this play straddles the change between the radio drama interested in exterior spaces of space and time,” says Verma, “and a radio drama much more interested in using sound to illustrate interiority and inner turmoil.”

He has a lot more to say about the play. “We’ll have to look at all our material in January, and we might do [another] book.”