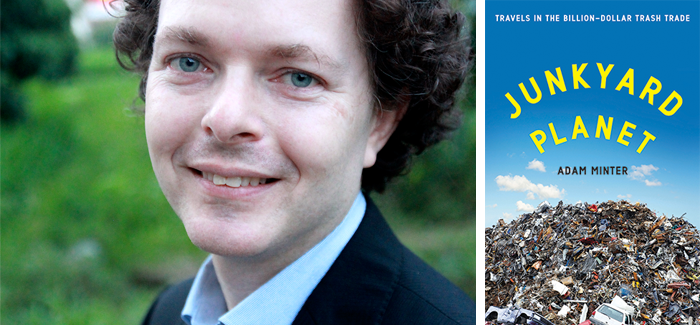

(Photos courtesy Bloomsbury Press)

Author Adam Minter, AB’93, weighs in on the wide world of waste.

A high-tech Japanese recycling company called Econecol has a facility in the forest at the foot of Mount Fuji. Adam Minter, AB’93, visited the plant while working on his book, Junkyard Planet, but what he saw there didn’t make it into his narrative of “travels in the billion-dollar trash trade.”

Ask him about the most memorable sights and sounds from those travels, though, and Minter recalls the invitation he received after seeing Econecol’s automobile shredding and sorting machines.

“Do you want to see the pachinko recycling?”

Minter, who grew up around his family’s Minneapolis junkyard and has reported on the industry from Asia since 2002, wanted to see that very much.

A ride down a winding road led him to a warehouse where the colorful, pinball-like devices that are a popular gambling pastime in Japan were stacked by the hundreds. “I remember there were Star Wars pachinko machines,” Minter says. “That stuck in my mind.”

Pachinko parlor operators, he learned, replace machines every few months because customers get tired of them. They are often of very high quality, gold-plated—“not gold-painted”—with state-of-the-art HD touchscreens. Econecol takes them apart to feed the market for those component parts. “They were extracting these touchscreens and packing them in foam and shipping them off to China where they were remanufactured into GPS devices and other stuff,” Minter says. “It was just amazing to me.”

Minter’s sense of amazement at the ingenuity and scale of recycling technology permeates Junkyard Planet. He details problems as well as progress, but his personal history gives him an appreciation for the characters and their accomplishments in an obscure, misunderstood industry.

Meeting Scott Newell, the CEO of a company that supplies metal shredders, thrilled him. Newell is the son of Alton Newell, whose design for a “machine that eats cars whole” helped solve an American epidemic of abandoned automobiles. “If there was an environmental Mount Rushmore in the United States, Alton Newell should be on it,” Minter says, “along with guys like Leonard Fritz.”

Fritz, who died in August, began “grubbing” around Detroit-area dumps in 1931 as a nine-year-old in need of money for school clothes. With a lot of effort, and more than a little luck, in less than a decade he made enough to build a business that would become the behemoth Huron Valley Steel Corporation. The company grew by virtue of its proximity to Detroit’s auto industry, salvaging and selling scrap from cars, but it has never become too big to let pennies go to waste.

Today, even as it receives more than half a billion pounds of scrap metal a year for recycling, Huron Valley Steel still harvests loose change. The cars in American junkyards have an average of $1.65 jangling around under the floor mats and between the seats. Gathering coins using a proprietary process—which Minter witnessed and declares “awesome”—the company returns them to the US Treasury in exchange for a percentage of the overall value. “They’re making money from money,” Minter says. “How great is that?”

Making money, not saving the earth, is the impulse that drives innovation in industrial design and waste management. “I’m a U of C guy, so I believe in markets,” the former philosophy major says. “I’m also a junkyard kid. I do think that markets are going to drive a lot of this change.”

The price of copper, for example, has increased from about a dollar a pound in the 1980s at his family’s Minneapolis scrapyard to as much as $3.50 today. Those costs force manufacturers to factor efficiencies into their designs—thinner or fewer wires, alternative materials—that have a net environmental benefit, but the economic incentives sometimes reward wasteful production. “I’m also enough of a pragmatist,” Minter says, “to know that markets aren’t going to solve everything.”

A policy in China gives electronics manufacturers a visible hand, imposing a fee that subsidizes the recycling of e-waste. After Japan instituted a similar program, Minter says, manufacturers and recyclers began working together to find more efficient practices.

Although he’s a satisfied iPhone 4S user—resisting an upgrade on environmental principle—Minter criticizes Apple’s products from a sustainability perspective. Its iPads cannot easily be taken apart and must be shredded to extract reusable materials, he says, a process that has sometimes caused them to burst into flames.

The company also collects used iPhones to recycle but “probably 30 percent of that phone is going to end up in a landfill,” Minter says. “As I describe in the book, this is ultimately a way to encourage people to buy more phones. Greenwashing.”

That compromises the virtuous circle of reduce, reuse, recycle. High recycling rates, in Minter’s experience, tend to be associated with poverty, which makes reuse a financial necessity. Among the wealthy, it often goes hand in hand with increased consumption, diminishing the environmental value of bins full of Amazon boxes. For those who consider conservation their ultimate goal, he suggests “stop buying so much crap in the first place.”

Minter, a columnist for Bloomberg living in Kuala Lumpur after 11 years in Shanghai, tries to live by that mantra. He uses refurbished laptops and hangs on to that old iPhone despite the flashbulb going off every time he turns on the screen. He and his wife, Christine, don’t own a car, relying on public transit. Packaging informs their shopping decisions.

While on tour to promote Junkyard Planet, though, Minter found himself in “the uncomfortable role of being Mr. Sustainability.” A simple calculation of the carbon burned on his research trips, he says with a laugh, would disabuse people of that notion.

Minter plans more travel this summer for his next book. He won’t divulge the subject, saying only that it’s about another overlooked industry but unrelated to the trash trade—ideas being one of the few commodities Minter finds no value in reusing.