After its long journey, the Land Rover gets a rest at Jai Mahal Palace Hotel in Jaipur, India. (Photos courtesy Lloyd and Susanne Rudolph)

In 1956, two new PhDs drove a Land Rover from Austria to India to begin the research that would be their life’s work. Notes from their journey.

September 1956

Our trip diary was written under challenging conditions. We jotted down the first half while the car was passing from one country to another on moderately respectable roads. But when we reached Persia, we could no longer write in the car—all our attention was devoted to keeping our stomachs below our lungs and not bumping our heads on the car ceiling. So the second half was written at greater leisure from notes as we recuperated from the trip in Lahore, New Delhi, and Jaipur.

We consider Salzburg the official starting point of our trip because we delayed in England and Germany along the way. Our vehicle was a new model of the Land Rover; the 107-inch wheelbase, five-door station wagon seated ten people and looked like an armored car meant for a battalion. The car was blue grey with a white tropical roof set on top of the ordinary roof.

The Rover made up into a bed. The second seat flattened out, the back of the front seat was laid across the back benches, and the cushions from the front seats made headrests. Since we carried all our luggage with us, we had to transfer it out of the back of the car into the front seat each night before we could make up the bed. We routinized this process enough so that it became quite simple. Lloyd usually made the bed while Sue prepared the supper.

Before the journey: the Land Rover being washed in Germany, July 1956.

For cooking, we had a Higgins two-burner gas stove, which we set just inside the door in the rear of the car. For breakfast and supper we put up our little wooden tables and folding chairs, set the table with paper napkins and plastic dishes, and tried to keep a gently civilized routine.

After dinner, we washed dishes in hot, soapy water in our folding rubber dishpan; sometimes we washed out a few clothes and hung them on a line tied to a nearby tree. In the mornings, while Sue cooked breakfast, Lloyd propped his mirror on the spare tire screwed on top of the hood, perched the pot with hot shaving water on the fender, and shaved. Keeping house on the road was always some trouble. But it refreshed and strengthened us as no hotel stay ever did. We’re not quite sure why this was so, but we think the manipulation of household equipment gave us the sense of being more than mere rootless wanderers upon the face of the earth.

We left Salzburg July 26 and arrived in Peshawar August 20, a matter of 25 days. The mileage was 5,114 miles, and the cost of the trip was about $300. The pretrip expenses incurred because we wanted to make the trip by car came to another $384.

Such a trip is an enormously rewarding experience for the strong of limb and stout of heart. The fact that everything is new and strange and possibly threatening creates a chronic underlying strain, a fear of the unknown which one must learn to live with. Such a trip is a calculated risk. But anyone who is in good physical condition, with a balanced psyche, a good car, a bit of luck, and a capacity to improvise can make the trip.

July 26 / Salzburg

Did big laundry on glorious sunny morning at camp outside Salzburg. All the laundry accumulated on the drive down through Germany. Sue reveling in domesticity, Lloyd champing at the bit. Drove into Salzburg with laundry triumphantly flapping on nylon laundry lines in back of car. Money for which we’d been waiting for three days finally came. Ate some kuchen and coffee to celebrate. Did some more quick shopping. Salzburg shops wonderful. Many tempting things. Bought some Landjäger for emergencies, piece of good bacon for outdoor breakfast, peaches, tomatoes, butter. Off at two for Graz.

July 27 / Graz to Zagreb

On the way toward Zagreb we came through Friday evening festivities. Truckloads of country people coming together at an inn garden near Varaždin—violins, dancing, and beer. The army, which we found in evidence throughout the country, was also on the road in companies on trucks. To get through the crowds on the roads, the trucks beeped furiously, and we soon followed behind, also tooting noisily and happily. July 28, we later found out, is the date on which the old Croatian government was replaced by the present one, and celebration was already beginning.

July 30 / Serbia to Thessaloníki

Woke up at 5:30. Everybody on the way to Monday morning market. Women with quacking ducks in their baskets, clean white cloths over their heads with roses pinned on. Bullocks, calves, tomatoes, peppers, all on the way to the market. Having no fixings for breakfast, we followed the crowd, after a lengthy discussion with a passing farmer who offered Lloyd a cigarette from a silver case.

As we headed south during the day, the farmland decreased and the herding of sheep increased. Finally, as we came out of the relatively flat farmland of Serbia into the arid, wild, and lonesome hill country of Macedonia, even sheep became rare.

On the way toward Thessaloníki, we began to encounter a strange phenomenon, so strange that we thought we’d had too long a day of it. Small trees moved silently across the road in front of us. Huge bushes slowly growled down the highway toward us. Agitated flora enlivened the roadsides. The bushes, we eventually realized, were heavily camouflaged troop transports with their lights out, the lively greenery camouflaged men. We, of course, had our lights shining brightly, essential if we were not to annihilate a donkey and his guide every ten yards. But the transports became more frequent, their drivers signaled to us to put down our lights, and eventually an armed sentry stepped into the road and halted us. For five minutes before that, we had been reviewing the recent history of Greco-Yugoslavian relations and theorizing that the Yugoslavian troop movements we had seen on the other side of the border and the Greek troops we saw on the move now might have some mutually antagonistic aim. But our sentry, who made us pull off the road and join a group of donkeys, farmers, and Italian motorcyclists, which he had already collected there, quickly eased our minds. War games, big ones, and ones to which Turkey and England had, incidentally, not been invited.

[As it turned out, the English, French, and Israeli invasion of Egypt began soon after President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal on July 26, 1956. Yugoslavia and Greece were mobilizing against each other just in case.—L. R.]

Our detainer spoke French and had studied political science at the University of Athens. He and his colleagues fed us and the Italian motorcyclists fresh watermelon, and when we got tired of waiting after an hour and proposed to park somewhere and spend the night, they found a place for us behind their own bivouac.

July 31 / Thessaloníki to Alexandroúpoli

We left Thessaloníki about 10 a.m. and drove to Alexandroúpoli by 8 p.m. In the meantime, we made the extensive acquaintance of the Greek police—a snappy corps, with their well-kept green uniforms and uniformly large black mustaches. At about 1 p.m., a mile outside the beautiful city of Kavála on the Aegean, we were arrested. But the arrest soon deteriorated into absurdity: no one could communicate the charge to us.

Our policeman called in a passing army officer for consultation. The officer was no help, but he used the word “Russki” frequently enough that we tentatively concluded this had something to do with (a) last night’s maneuvers and (b) we were suspected of being Russkis, spying no doubt. This impression was confirmed when the policeman got into our car and directed us to a nearby army encampment.

A few moments later a noncom emerged from one of the red corrugated iron Quonset huts that sat among the trees. He spoke English and informed us that we were charged with killing a cow with our car. Someone had seen us do it and taken down our number.

The long and the short of this story is: it wasn’t a cow, it was a horse, and we didn’t do it. Fortunately we saw the accident, or the confusion would have lasted much longer. The horse had run into the path of a defenseless Volkswagen, knocking in the VW’s nose and one light and killing itself. We stopped to see if we could help, because we had met the Iranian driver and his young German bride at the Greek customs. While we were explaining this story to the police, the VW drove up, looking duly bashed. The Iranian, one of the tensest men we have ever met, was all for telling the police that his wife was pregnant with quintuplets and they couldn’t stay to answer questions, but his calmer wife dissuaded him. We translated their story to our interpreter who translated to the police. When we last saw them, they were returning to the site of the act, where they were to argue their case before the local police. We felt sorry for them—it would be awkward arguing with an irate Greek farmer and the Greek police in German and Persian.

We arrived in Alexandroúpoli via worsening roads, after dark, in time to see people flocking through the main streets in the evening cool.

August 2 / Istanbul

The traffic here is very thick, and the trolleys carry crowds of people including always a contingent of five or six little boys who jump on the back and hold on to god only knows what with their bare toes and hands. The Istanbul police wear snappy white coats (wool!) and blue trousers and are very helpful. As far as traffic in Turkey in general is concerned, there are many American cars in the big cities and some in the country. People rely on brakes rather than on a generally accepted conception of the right of way. Lloyd was always fit to be tied after an hour’s driving in any city. In the provincial towns the automobile has not yet received recognition of its rights on a par with cows, donkeys, people, and other users of the right-of-way.

We still haven’t killed a chicken—a truly glorious record.

The Rudolphs in 1990 with Ramaswamy Venkataraman (center), the eighth president of India, and his wife. At left is Gandhi’s grandson Gopalkrishna Gandhi, then secretary to the president.

August 4 / Ankara

On to Ankara. The city itself is very attractive with its parks, boulevards, and public monuments. At four in the afternoon we plunged back into the forbidding, arid country. No appealing campsites appeared anywhere, and the people looked unfriendly when we slowed down to inspect a possible site. Finally, near Sungurlu, we saw a village in the distance on a hillside. We turned off the road that led to it and parked in a dry streambed which looked promising. But before we got very far in unloading the car, four farmers arrived and investigated our arrangements. They gave us to understand that the mosquitoes were bad at our site, and one farmer motioned toward a nearby house where tractor-powered machinery was thrashing some crop.

There we parked and started supper. Pretty soon the word got out, and more farmers started assembling, sitting in a large half circle around us, watching every move of the preparation. Evening show! Good instinct of showmanship required to survive such an experience. The prosperous though quite unshaven farmer who had asked us there soon brought out an enormous plate of curds. Lloyd had no trouble with this unsolicited gift, but Sue, who can scarcely face even milk, turned a little pale. But everyone was watching—not a chance of disposing of it by any manner other than eating it.

When the daylight finally faded, the helpful farmers brought over the tractor, turned its lights full on us, and critically observed our bedtime ablutions. Nothing like brushing your teeth with 20 men watching intently! Late show! We were pretty tired by this time and most troubled about how we’d tell our audience that the show was over. We made up the bed, drew the curtains, came over to face our audience directly, bowed in unison, and said good night. The farmers murmured a friendly return greeting, lumbered to their feet, and went away, avidly discussing the evening’s events among themselves.

The trip from Samsun to Trabzon was magnificent. The view from the heights, across green hazelnut groves and red tile roofs, fell to the Black Sea. We arrived in Trabzon after dark and, after some inquiries, were directed to headquarters of a US military group. These were in a large house behind the usual wall at the top of a narrow, steeply pitched alley that led at a 45-degree angle to closely set buildings and walls. Five or six men were lounging in T-shirts in a large room next to a pantry where our furtive looks could catch glimpses of Campbell’s tomato soup and corned beef hash. They appeared to be not at all surprised to see visitors from the States and were cordial and immediately responded to our inquiries about a place to camp with a suggestion of the local radar installation. We slept that night on top of a mountain immediately outside the barbed wire of the radar installation.

[We assume that the radar installation was part of a missile site whose weapons were aimed at the Soviet Union. These are the missiles that President Kennedy had covertly agreed to remove as a condition of solving the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962.—L. R.]

August 6 / Erzurum

Glorious drive from Trabzon to Erzurum, through mountains reminiscent of the Salzkammergut. Slow driving because of many curves. Apricot country. The dry lowlands were relieved by rows of tall poplars, obviously planted by someone anxious to add greenery. Above Erzurum, at a number of small towns, we began to notice a proliferation of the army installations which were prominent throughout Turkey. All appeared in a high state of readiness: hundreds of trucks lined up in apple-pie order, jeeps, half-tracks, and all in great quantity. Before Erzurum itself we passed the climactic one of these establishments.

We were just remarking to each other that for a determined spy the situation around Erzurum would be sheer duck soup, when we were flagged down by an armed soldier. Our passports were demanded and swiftly borne off. A half hour later a junior officer returned with them, and in his sparse German cheerfully indicated that he would now climb into our vehicle and accompany us elsewhere. Fifteen miles later we entered Erzurum. Eventually our passports were left at the police station, after being registered in immense, painfully written record books at two guard houses on the way. We were told we might pick them up in the morning, and where, please, did we plan to spend the night? In the car! Well, then our companion would arrange to find a place to park the car in the garden of the city jail.

August 7 / Erzurum to Maku

After breakfast we picked up our passports and a soldier who escorted us 40 miles beyond Erzurum, through extended training areas which Lloyd identified as engineering, artillery, armor, and transportation.

The reason for the large concentration of men and equipment in this area is plain on the map. Erzurum is the closest major city to the Russian border along the main overland route from Russia into Turkey. As far as we could see, the Turks have much more equipment than the Yugoslavs. Their soldiery is not nearly as spiffy in appearance as that of the Greeks but approximates that of the Yugoslavs. But we were impressed with their apparent preparation.

Just inside Iran, we arrived at the small town of Maku.

August 9 / Maku toward Tehran

Another grueling day of dull driving. Hills and plains all equally dry. Our one amusement was the camels which we now began to encounter in large numbers. They are great, lumbering, pompous beings, who peer along their noses with an air of contempt while chewing with their big, soft, fuzzy lips. Their gait is loose and uncoordinated looking when they run, though they have a fine swaying and dipping rhythm when they walk. They are led by a rope attached to a pin in their noses, a necessary device since they are often ornery. They are still a very important means of transport in these parts, though more so east of Tehran than west of it.

We hoped to get to Tehran that night, but the last 60 miles turned out to be the worst we had yet encountered —dusty, with potholes, washouts, and dangerous places everywhere. Yet this road was the busiest we had seen in all of Persia, buzzing with the incredibly high, overloaded trucks which are the bane of its roads and which here and there lie toppled by their load into ditches. To stay behind these trucks on the road was death, because the diesel smoke and dust would blind and poison you. To pass was disaster, because if the black diesel smoke came from a left-hand exhaust all view was obscured, even of bright oncoming headlights; if you got through the smoke the chances were a washout on the left would catch you. After two hours struggling, in which we covered 30 miles, we gave up, pulled off the road into the desert, which bore only a prickly, unkind weed on its dry face, and made camp in the dark. We ate more dried fruit, but we were so tired we had almost no appetite. Our ritual ablutions—washing the face and brushing the teeth keep men human—comforted us and we instantly fell asleep.

August 11 / Tehran

At 6:30 we met with Hugh Carless, the new secretary of the Tehran Embassy. Laughing, we told him of a story Lloyd had heard from a warrant officer who had served at the embassy in Kabul. The story concerned a diplomatic car held up by bandits on the road from Kabul to Peshawar. The car had been robbed and diplomatic files scattered over the Afghan hills. We said we realized that this was just another one of those popular horror stories people like to tell prospective travelers. Carless laughed agreeably and added conversationally, “Yes, I was in that car.”

When we had recovered, he related the following tale: it seems that a disaffected tribe had contrived an ambush on this road, which goes in part through steep canyons and is quite vulnerable to attack. Carless’s car had been the first stopped, and its occupants were put in a nearby canyon and guarded, while for the next three hours other cars and lorries were held up in the same ambush. One lorry was accompanied by two soldiers, seated on top. One soldier, either through extreme courage or extreme stupidity, fired his gun. He was instantly shot. The other soldier sought to jump down to surrender, but his motives were misunderstood, and he too was shot.

August 13 / Mashhad

On to Mashhad. We stopped at Sabzeva¯r to take a picture of a funny mosque with aluminium-topped minarets. The crowd that gathered to watch us was rude, and the children very fresh. We drove off quite angry. In the medium-sized cities after Tehran where we stopped this was often the case. A batch of just prepuberty males would gather around, stick their heads in the window unless Lloyd growled, and make remarks which sounded no less fresh for being in Farsi. We had the feeling, although no evidence, that the extraordinary sight of an unveiled, bare-legged woman led them to suppose that such an immoral phenomenon invited disrespect. The women became increasingly more veiled as we moved east—the large black or dark blue cotton shawl, worn as a cloak over the ordinary Western-style clothes which all the city women and many provincial women wear, is rarely drawn over the face in Tehran, where women even use lipstick. But eastward, the face is more rarely seen, and the casual gesture of hiding the face becomes more purposeful, until finally women squat down, turn away, and draw the veil when a car passes. By the time we arrived in Mashhad, Sue was feeling self-conscious about her face showing—if people look at it as though it were naked, then gradually the supposition arises that it is naked.

While we were looking for the way to the consulate, four young Iranians accosted us and offered their help. Two of them, it turned out, were taking English lessons several nights a week and were very anxious to practice it. They were perhaps 17 or 18 and eager to hear about America and Western habits in general. The brighter one of the two was the son of a Persian rug merchant. The other, an engineering student, told us that Mosaddeq [deposed by the CIA in 1953—L. R.] was very popular still, though he had little chance for a comeback because he would not be permitted to hold public office. They invited us for tea and apple juice at a little ice cream parlor and escorted us safely back to the hotel.

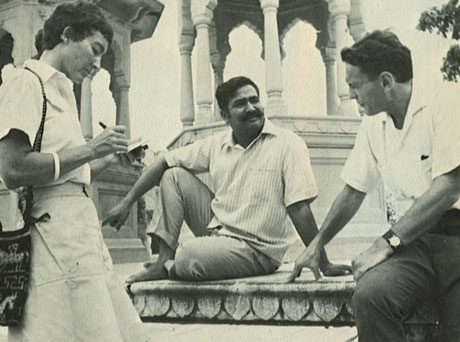

The Rudolphs in 1971 with Mohan Singh Kanota (center), who worked with them on Reversing the Gaze.

August 14 / Mashhad to Herat

We met the consul, Robert Schott, at the consulate. The day of our trip preceded by only one day the great and sorrowful feast day of the Shiite Muslims commemorating the death of Hussein, a descendant of the prophet and, according to the Shias, his true heir. Mashhad, with its great shrine containing the tomb of Imam Reza, is a famous pilgrimage center for the Shias, and the death day of Hussein is the culmination of months of sorrowing, comparable in a sense to Lent and Good Friday. Foreigners are not welcome at these times of great religious significance.

We went to the bazaar with some trepidation, after Sue had modified her wanton appearance with a scarf over her head. Because of the impending feast, all money changers in the bazaar were closed. We were about to give up, when our Iranian consulate guide came back from some inquiries and announced: “One Jew is open.” Apparently the ancient profession is still practiced in these parts by the people of the Book, and they are not bound by the Muslim rules. The money changer quoted us an acceptable rate and then went off to see if he could round up enough Afghanis to cover the deal. He told us the transaction would take another 20 minutes.

By this time a crowd was beginning to gather, and while the men seemed mostly curious and not unfriendly, an inordinate number of little boys were accidentally taking running starts and bumping into Sue, without being chased off by the adults. Schott suggested we leave the consulate servant there to finish the transaction and start back to the consulate. Halfway through the bazaar we heard chanting ahead and caught glimpses of black prayer flags. Schott hastily shepherded us into a nearby bake shop, and only just in time. The chanting signaled the approach of a mourning procession on its way to a shrine in the bazaar. Men bearing the flags came first, followed by a slow-moving array of mourners—men with shaven heads wearing loose, black, sleeveless gowns cut out to expose the shoulder blades. They carried short clubs to whose heads were attached some 20 thin metal chains, and with these they beat their exposed backs rhythmically as they walked—the self-flagellation was not violent, but steady and ritually patterned. As they passed we huddled toward the rear of the bake shop and watched the bakers at work.

We left Mashhad around 1 p.m. after equipping ourselves with tire patches. We were guided to the road to Herat by a boy from the local Land Rover agent. Night fell as we passed through the no man’s land between the frontiers, past the Persian border guards with their fixed bayonets gleaming in the early moon. After half an hour’s driving, a border barrier loomed out of the darkness, and on the right rose the shadow of an old fort. The Afghan border guards cheerfully pumped Lloyd’s hand in greeting, glanced at our passports, and indicated that one of them would now climb in to take us to some unknown destination ahead.

Though Afghanistan imposes a stricter purdah on its women than any other Muslim country we passed through, the men were relaxed in their greetings to Sue. Since she was plainly not of a category with their women, they apparently treated her in the only other plausible way—as a man.

August 15 / Herat

The mile markers which had guided us through Persia now disappeared. They had served their function: teaching us Persian numerals, which we had to know for the financial transactions—we usually bargained by having a vendor write the amount on the dusty surface of our car door, and then writing the bargaining figure underneath.

The land from the Afghan border to Herat did not differ greatly from the last part of Persia. One difference was the road, which immediately announced that in Afghanistan we should not expect to travel more than 20 mph, and that the bouncing we had gotten on some Persian roads was insignificant.

Another difference was a powerful hot wind, or loo, which began to blow when we were not far into Afghanistan. It whipped up the dust and sand from the arid land and chased it over the road. When we stopped, as we had to four times that morning to readjust and eventually completely reload the equipment in the back, it blew so strongly that we had trouble moving about. Once it tore the wooden folding table from Sue’s hands. This is the “wind of 120 days” for which the area is famous—or infamous. Its unhesitating persistence tires the body and irritates the spirit. We were almost spitting at one another after an hour of it.

The terrible, uneven road where even 15 mph was no guarantee against bounces that would send us flying out of our seats, produced several disasters. The new aluminium water container, bought in Tehran, was crushed to an octagonal shape, and eventually the metal side gave way and the back of the car was flooded. We had six large book packages, wrapped in heavy paper, lying under the middle seat where the water could reach them. So 20 miles out of Herat we had to stop, rush around to save the packages, and mop up the back. But the wind had its virtues: it dried the book packages off quickly. Subsequently we discovered that only one book had been hurt, but that unfortunately was Lloyd’s thesis (the binding).

We arrived at Herat around 12:30. We saw its smokestacks—what industry could Herat have that requires four smokestacks?—rising in the distance some time before we reached the approach avenues, which, though still uneven and graveled, are lined with beautiful coniferous trees of a kind we had not met before. The weary traveler from the countryside must find these a great relief as he goes to the city market to sell his goods. We certainly did. As we entered the city, we discovered that the smokestacks were broken-off minarets, the remains of an ancient university that dominated the East when Herat was a great center of culture and learning in the l6th century.

Everywhere frantic decorating was in progress in preparation for the Jeshyn, or Independence Day Celebration, which would begin August 24 and last a week. It marks the successful end of the last Afghan war, which finished British influence in Afghanistan. The man who won this independence for the Afghans, the former King Ama¯nulla¯h, was apparently cut of the same cloth as Atatürk. He sought to modernize his country and among other things to take the women out of purdah. On this ground and others he incurred the wrath of the conservative elements, especially the mullahs, and was ousted.

We heard more talk of history and politics in Afghanistan than in any other land en route, both from Afghans and foreigners. We knew little more of the country than that it had traditionally been the invasion (and trade) route to India; that therefore the British and Russians had spent a substantial part of the 19th century meddling in Afghan politics trying to create a situation favorable to themselves; that Afghanistan, though drawn into the British sphere of influence as far as its foreign policy was concerned, had resisted any real colonization and that the old game of seeking influence was not over, but had gotten some new players—notably the United States.

Afghanistan was plainly the wildest country we visited. The absence of even a rudimentary communications system, as well as of other evidence of Western impact, led us to speculate on the virtues and vices of colonialism. The Afghans were totally unapologetic about their lack of knowledge of Western manners and ways. (Kabul may be an exception.) Elsewhere we had found people apologizing if they couldn’t speak English. Here there was some surprise that we couldn’t speak Farsi or Pashto. An Indian acquaintance who spent time in jail as a nationalist has told us that he is often unintentionally resentful of Westerners because “I forget that we are free.”

This outlook has its negative side. Afghanistan presents an example of l6th- and 17th-century-style Oriental autocracy caught up in 20th-century power political problems. Like the autocracies of an earlier era, Afghan politics are family politics uninformed by any regularized determination of popular will—though elaborate claims of constitutional monarchy are made.

The atmosphere in Kabul breathes intrigue, largely because speech, communications, and political decision making must flow through subterranean channels—they are by no means free and open. The Westerners to whom we spoke in Kabul, almost to a man, referred to Afghanistan as a “police state.” To us the term seemed a misnomer—it conjures up visions of highly rationalized, bureaucratized, technologized Western-style dictatorship. What exists in Afghanistan seemed to us more an ancient arrangement which had never heard of the liberal tradition and didn’t want to hear of it, than a modern arrangement seeking to suppress it.

Picnicking in Rajasthan, India. Most of the photos from the trip were destroyed in a flood in Chicago.

August 16 / Farāh

We reached Farāh around 1 p.m. and set off at 5 p.m. to tackle the desert road. We had been told that no one tackles it in the daytime, and we agree that no one should. This night’s driving was a sheer endurance run. The road was not just rough but downright treacherous. About 11 p.m. we came to a village. The tea house looked inviting: two winking lamps strung up above a huge copper samovar standing in the open shop front, nearby a dark wooden rack with bright-colored teacups and teapots, some small Persian rugs on the floor near the samovar, and on one side five men in turbans sitting in a circle sipping tea. We parked and came over, requested “chay.” The proprietor, a young man, quickly brought the round pot (known as china in these parts, a splendid Persian word) and cups, a little bowl to put in tea leaves when you finished a cup, and a container of rough-grain sugar. When we were ready to leave, Lloyd opened negotiations for payment, but one of the turbaned men rose and dismissed the possibility of payment.

At Gereshk the road changed—suddenly at 4 a.m., when the darkness was lifting and we were tired to death of the driving, there appeared before us a well-graded, freshly graveled smooth road with new bridges. This is the road that the Americans are said to have helped with, and we blessed American materialism with all our hearts as we sped along the next 60 miles to Kandahar at 50 mph.

August 17 / Kandahar

We found the Kandahar hotel, another gaily painted stucco structure, and were received by a rather inept manager in Western bush shirt and trousers, with Western pretensions but no real feeling for hospitality. Our ruder hosts at Farāh and Herat were much nicer. He couldn’t make up his mind for a while whether he could really serve us lunch already at 11 a.m. (We had had no full meal since the previous afternoon.) Once he made up his mind to do so, the food was unattractively served—even by our now modest standards. Sue met three people in the lobby, all of whom spoke German. They asked if she and Lloyd would take one of them, a tall Austrian young man with a fish-belly-colored, unappealing appearance, to Kabul. He was a professional world traveler, on the road one year already and financing himself with the proceeds of lectures and slide shows. Subsequently he brought out a large scrapbook in which were displayed pictures of himself with “significant” personalities around the world: “Here I am with the chief police inspector of Baghdad.” “Here I am with Ibn Sa‘ud’s son.” “Here I am on Radio Cairo.”

We had discovered, by the way, that there are numerous types of world travelers. But there seems to be one kind that makes all embassies from Yugoslavia to Kabul flinch. He is the fellow on his way around the world on $15, and here he is in Mashhad, halfway round, and he still has $13. There are surely some fine men among these, but the typical example seems to feel that because he has been brave or harebrained enough to attempt this extraordinary adventure, he can expect all Europeans along the way to meet all his demands, outrageous and otherwise. The embassies further east, where the going is tough, seem to have had their fill of such types. We found some consular and embassy officials very wary when we first met them to ask for local advice. They all relaxed and turned out to be warm and helpful eventually, but only after they found we were not expecting them to supply food, lodging, gas, and guide service free of charge. The Yale group which came through last summer, though they were probably not of the $15 variety, made a poor impression by insisting on gas at the Kabul embassy as a matter of right and not paying for it (or not paying adequately, we are not sure which).

In any case, Sue put off the world traveler, hoping for Lloyd’s return and a bolder refusal. We picked up riders several times on our trip, but except for the Turk who went with us to Trabzon, we never took anyone for long distances. It would be a good man whom one could like after a day of heat on those terrible roads. The ride to Kabul was overnight besides, and we didn’t relish the prospect of having to search for accommodations for a third person, when we could simply stop anywhere. Meanwhile the Austrian further endeared himself to Sue by some authoritative lecturing on the atrocities which the Americans had committed against the Germans during the Second World War.

August 18 / Kabul

After a day in Kandahar, we set out for Kabul, reaching it after dark. The marine guard at the embassy told us that possibly the International Cooperation Administration (ICA) staff house might have some room, but he couldn’t raise them by phone. We were already getting ready to pull the curtains and sleep in the streets of Kabul, when it occurred to us to ask for directions to the staff house. We got some rather general ones and started prowling up and down alleys looking for it. Just as we were about to give up in a new burst of desperation, we heard laughing and English voices down the street—a somewhat entwined Western couple, who turned out to be young UNESCO personnel. They knew where the staff house was and took us there.

The UNESCO girl, who turned out to be endowed with limitless brass, commanded the Afghan who opened the door to admit us all. “Where was the manager?” she inquired. “Miss Poindexter is asleep.” (It was then 8:30 p.m.) “Wake her up!” “Oh no, Madame. Miss Poindexter would kill me.” “Well then, which of your rooms is empty? Where can these people sleep?”

The servant reluctantly allowed that one room was empty. Our intrepid friend inspected it critically and conceded that it might be all right for us. (Best place we’d seen since Tehran.) She then ordered the servant into the kitchen to prepare tea sandwiches and, after having quieted our misgivings about crashing the house this way, swept off gaily with her more diffident young man.

In 1990 the authors received the Colonel James Tod Award, recognizing foreign nationals who have contributed to the understanding of the Indian state Mewar.

August 20 / Peshawar

We had promised ourselves that the arrival in Peshawar would be considered the official end of our journey. The last lap was easy. The road from Kabul to Peshawar is much better than roads anywhere else in the country. The last stretch is very attractive—instead of the flat, high plateau we finally found mountains. We followed the roaring Kabul River, a joy to our eyes after the dry 2,000 miles before.

We reached the Pakistan border at seven, when it legally closes, but border officials gave us sweet green tea and let us go on, along the marvelous blacktop road which starts immediately on the other side of the Afghan border. They provided us with a guard from the border constabulary, a tough-looking Pashtun in khaki shorts and shirt, a decorated turban, bearing a rifle with fixed bayonet. Since the car was full, he had to climb in next to Sue, which he accomplished after a first attempt to climb with his heavy boots on the seat and into the back. Through the Khyber, which takes a half an hour to cross, and into Peshawar, he kept his heavy foot resolutely on Sue’s sandaled foot oblivious of her kicks at his ankle.

The Khyber is still not entirely safe, and frequently constabulary checkpoints have been erected to assure that no traveler is picked off by a roaring frontier tribe.

Out of the pass we emerged into the flatlands below, which looked more rich and fruitful in the dark than anything we had known since the Black Sea. Here and there, we saw signs of a highly organized society, compared to those we had left: the cantonment signs, the Civil Lines, the sign “Government High School,” the blacktop roads, the sign to the railway retiring room, the little officialisms in language that showed the English stamp. We almost had tears in our eyes and did not condemn completely the colonialism which had left such comforts.

We drove straight to Dean’s Hotel, a hotel in the British-Indian tradition, with fans, and dressing rooms, and flush toilets that worked, and a six-course menu. We were received into the gentle arms of a colonial-influenced civilization by five white-turbaned hotel servants. When the dessert, an English sweet, was brought on, and the tea was served with a pitcher of hot milk, we drank to England and to Pakistan and celebrated our emergence from the underdeveloped areas into the developed Indian subcontinent.