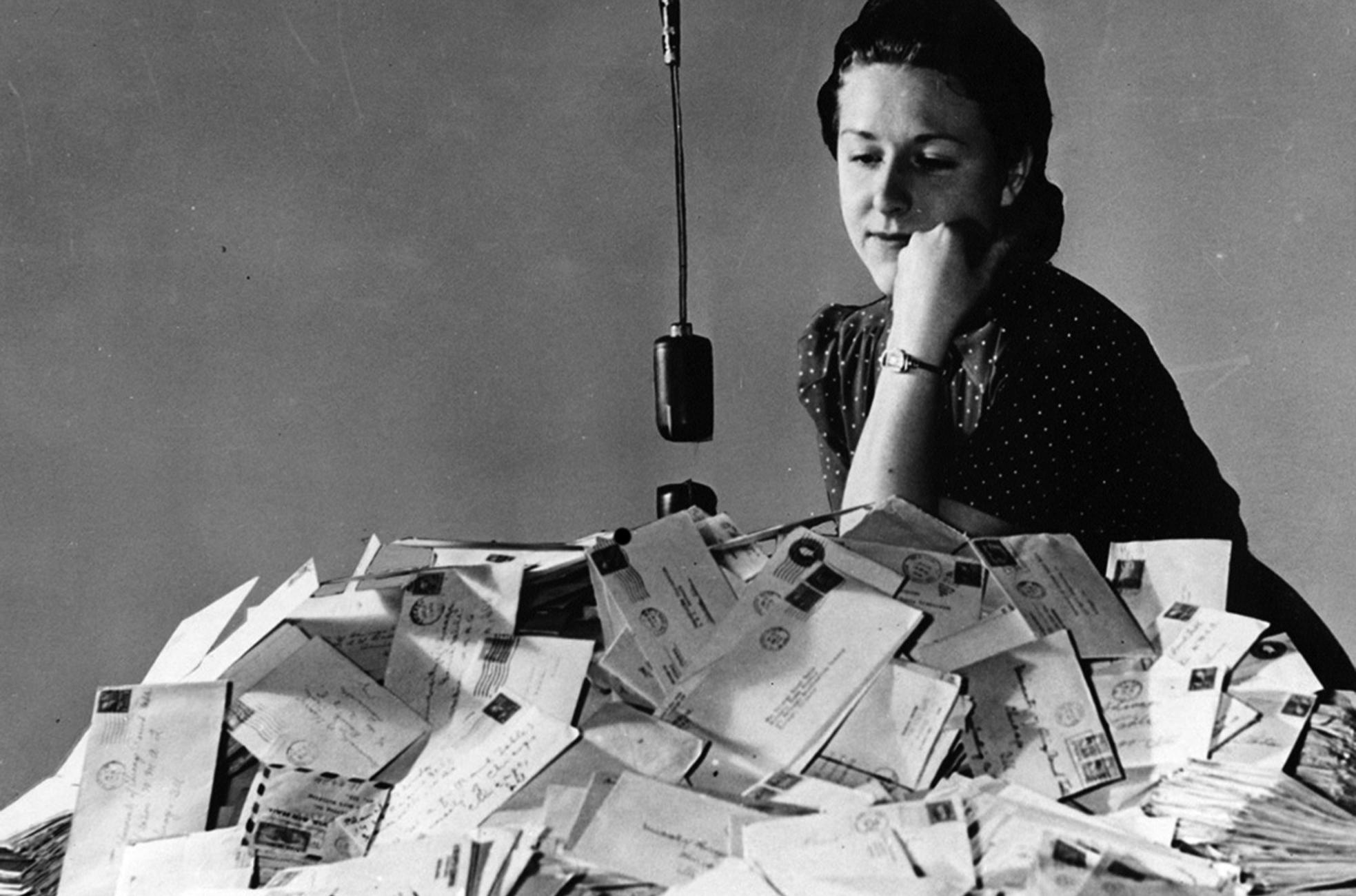

Listeners’ mail to the University of Chicago Round Table radio program, undated photo. (UChicago Photographic Archive, apf3-02383, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Your thoughts on the Calumet Quarter, a dean’s generosity, our CMOS quiz, and more.

The dance goes on

Reading Lucas McGranahan’s report about two recent Neubauer Collegium programs where “an intimate group” of academic elites pushed for more government regulation and redistribution (“Delicate Dance,” Fall/24), I was struck by how the November elections have overtaken that agenda. It seems that many ordinary Americans want no such thing.

Dismissing the “almost mythic” mid-20th-century view “that the American republic was founded by treating private property as sacrosanct,” needing protection from government interference, these worthies remind us that “even so-called free markets are made possible by state power … just as they are both sustained and hemmed in by that same power.”

Citing Milton Friedman, AM’33, and George Stigler, PhD’38, McGranahan is quick to note that “this is not the economic thinking UChicago is known for.” Really? I knew both men. In fact, Friedman, who sat on my dissertation committee in the philosophy department, was clear that free markets are impossible without the rule of law that free states secure. True, he and Stigler “advocated using markets to solve problems whenever possible,” as McGranahan writes, but they were arguing there not for anarchy but against the ubiquitous programs of the New Deal and Great Society.

That’s only the first of the straw men peppering this report—too many to address here—like the claim that neoliberalism “is an assault on the very idea of the public interest.” Nonsense. Liberal public-choice economists have long developed a rich theory of “public goods” arising from the free-rider problem.

Not surprisingly, the report concludes with a proposal for “the creation of a national investment authority to advance long-term national priorities,” an “800-pound gorilla” that would “get its hands dirty as a lender and guarantor in credit markets and as an asset manager and venture capitalist in equity markets.” Exactly what we need as our national debt, at this writing, has just surpassed $36 trillion.

Roger Pilon, AM’72, PhD’79

Washington, DC

Dunes messiah

Carrie Golus’s (AB’91, AM’93) wonderful story “Pipe Dreams” in the Fall/24 issue of The Core shined a bright light on the Calumet Region, whose crown jewel is the hauntingly beautiful Indiana Dunes lakeshore. The Calumet Quarter is a wonderful idea to provide University students—many of whom may be new to the Chicago area—with an idea of the adventures that lie just outside the city limits.

I grew up in gritty Hammond, Indiana, in the heart of the region, and earned a BA in 1977. The drive from my home to Hyde Park took under an hour, but I often marveled at the psychic and cultural chasm that separated the two. So close, and yet so far away.

Like most of my friends, we didn’t often go to the Dunes while growing up. It was only after I moved away and could see them with fresh eyes that I realized what a treasure they are—and what a miracle it is that they’ve survived, even while sharing space with hulking steel mills. Solitude is easy to find in the land- and seascape of the Dunes. Hell, if you don’t look across Lake Michigan at the Chicago skyline, you can even forget what century it is.

The article ably documents how the Dunes, with the diversity of plant life in a distinct ecosystem, took center stage in the development of the field of botany through the research of Henry Chandler Cowles, PhD 1898. But readers might be more surprised to learn of the enduring artistic and cultural legacy of the Indiana Dunes as exemplified by Frank V. Dudley, widely known as the Painter of the Dunes.

Dudley (1868–1957) was born in Wisconsin and made his home in Chicago, where he developed as a realist painter and became a vital member of the burgeoning Chicago artistic community. In the early 1900s, Dudley visited the Dunes and was struck by the area’s beauty and ever-shifting patterns of light and shadow. He was a key member of the Prairie Club, the bellwether of the Dunes conservation movement that began just before World War I. The Dunes were even then in the sights of industrial titans such as US Steel.

The creation of the Indiana Dunes State Park in 1923 was a key victory for the conservationists, but it also led to an unexpected development: What to do with the Prairie Club’s unofficial beachfront cottages—including the Dudleys’—that were now on state park land? The Indiana Department of Conservation came up with a novel solution: Dudley alone would be allowed to stay on in his cabin, his payment being “one large original oil painting by the Licensee, suitably framed. … This payment shall be made annually.” Many of those “rental” paintings are now in the Indiana State Museum in Indianapolis.

Ted Dupont, AB’77

Upper Montclair, New Jersey

Metcalf’s magnanimity

I’m not sure I regularly or ever read the Editor’s Notes in the Magazine, but I did in the Fall/24 issue (“Meet the Interns”). Maybe it was an accident, or maybe an unknown force said, “Read this.” As I read about the Metcalf interns, I recalled perhaps the most influential thing that happened to me during my 18 months at the University of Chicago.

After undergraduate school and a few years of full-time work as an engineer, I enrolled in the MBA program at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business (aka the GSB). At the time, I was married with two very young children and rented a third-floor walk-up in South Shore. Midway through my first year we were pregnant again, with the due date shortly after expected graduation in April 1969. Already short of cash and with (by then) a maxed-out student loan ($10,000 seems like a pittance today, but it represented about 40 percent of the price of the suburban home I purchased after graduation), I was living on the edge.

As I faced tuition for year two, it was evident that something needed to happen or year two would not happen. Enter Harold R. “Jeff” Metcalf, AM’53.

I went in to see Jeff, who was then dean of students for the business school as well as a regular attendee at Hyde Park watering holes and the Friday mixers in Business East. I explained to him that I had a problem. I was either going to be able to afford to live or to pay tuition, but not both. To the best of my recollection, and within no more than a short minute, Jeff said, “You live, and I’ll take care of the tuition.” Is this amazing, or what?

There was never a formal document nor my signature on anything. It just happened! Sometimes the bureaucracy wins and sometimes the good guys prevail. Needless to say, Jeff Metcalf was responsible for the successful completion of the most important educational event in my life.

It is certainly no surprise to me that this amazing internship program is named for Jeff Metcalf. He knew how to give back and is a role model for all of us.

Here’s to you, Jeff.

Bob James, MBA’69

Columbus, Ohio

Time check

With a master’s in English lit from UChicago, and as a writer, editor, and copy editor in the corporate communications field for the last 40 years, I always look forward to the Magazine for its well-written and illuminating letters and articles. So my interest was doubly piqued by The Chicago Manual of Style 18 piece and its little quiz (“CMOS 18 Is Here,” Fall/24). I won’t say what my score was, but my editorial pleasure (the satisfaction that only copy editors know, red pencils always at the ready) knew no bounds when I saw the factual error at the end of question 5. Aha, something to fix, I thought. And yet, I wondered, where else would the sly Magazine staff hide an editorial Easter egg but in an editorial quiz? I shall ponder this tomorrow morning as I walk my dog, once again enjoying the early morning light afforded by our fall back to standard time.

Steve Parker, AM’79

St. Charles, Illinois

Editors tend to be opinionated and can debate endlessly about arcana such as the appropriate places for commas, capital letters, and italics. I should know: When my wife, Lynn, and I got together, it turned out that between us we had no fewer than three copies of The Chicago Manual of Style. That meant that we could garner up to five opinions about any editorial matter: mine, Lynn’s, and as many as three more from the various editions of CMOS.

We therefore read with interest the squib about the new 18th edition of CMOS, took the little quiz, and debated whether CMOS was getting the answers right. The two of us are on the same page with respect to question 5: “Daylight saving time ends … [and] Chicago will go back to Central Standard Time and wake up to darker mornings.”

The point of this quiz question was new doctrine concerning the capitalization of the names of time zones, such as Central Standard Time. Well and good: We can reserve debate about that for some other time.

However, at least out here in California, where we live, when daylight saving time ends and we go back to Pacific Standard Time—note my use of capital letters—we get lighter mornings, not darker.

On this particular point, perhaps The Associated Press Stylebook is a better guide?

David Simon, SM’74

Los Altos, California

While we wish we could claim this time zone slipup was an Easter egg designed to delight attentive quiz takers, it was—alas!—something more mundane: an error, which we regret. We thank Parker, Simon, and the other alert readers who brought it to our attention.—Ed.

Supply and demand

On the lower level of Business East was a student lounge, and students met on Thursday afternoons at the LPF—Liquidity Preference Function—for beer and conversation (“Locker Room Talk,” Alumni News Snapshots, Fall/24). Liquidity preference is a theory of the English economist John Maynard Keynes.

Steven Georgeou, MBA’70

New York

Norman invasion

Your article about Rebecca McCarthy’s (AB’77) biography of Norman Maclean, PhD’40, pushed several buttons, prompting this letter (“Searching for a Story,” Summer/24) .

As a student in Maclean’s Modern Criticism class, what I remember most is his gruff manner and chain-smoking. But he also told an anecdote that has stuck with me. When T. S. Eliot was at the U of C for a lecture series (either in 1950 or 1959), Maclean asked “Tom” what he meant by the term “dissociation of sensibility,” which Eliot had coined in his 1921 essay on the metaphysical poets. After hemming and hawing, Eliot confessed that he had forgotten.

That anecdote may stick with me because it shows that Maclean possessed such a good “crap detector” (Hemingway). Your piece also mentions that Maclean never really committed himself to the scholar’s life, and that his breakthrough book was his memoir, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories.

Three other U of C English professors mentioned in the excerpt from McCarthy’s biography are Gwin Kolb, AM’46, PhD’49; David Bevington; and Elder Olson, AB’34, AM’35, PhD’38. Kolb saved my bacon by throwing me a Maclean-like softball during my 75-book exam. After I had muffed a hard question from a junior faculty member, Kolb asked, “Where was Uncle Toby injured?” “Shall I show you the place?” I replied. (The text to which we were referring was Tristram Shandy.)

Bevington was my thesis adviser. After several rounds of “I’m sorry to have to tell you,” I finally produced a cogent draft that he could approve.

When Olson unexpectedly turned up at my strategically planned summer dissertation defense, I panicked. But he only made one comment: “You could turn this thesis into a very useful book.”

Like Maclean, however, I followed a different path, becoming a teacher (for 44 years) and creative writer. (My 22nd and 23rd books will soon appear.) To whom do I owe my long dual career?

Ron Singer, AM’68, PhD’76

New York

I was pleased to see the article on the new biography of Norman Maclean in the Summer/24 issue. I took his Shakespeare course in 1959 or 1960, and I recall the no-nonsense directness he brought to class discussions and his care to make sure everyone who had something to say was heard.

I remember him remarking one day that Shakespeare’s plots could be analyzed in the same terms as a Mickey Spillane novel. I was young, naive, and a bit shocked at the idea of comparing Shakespeare and a writer of pulp novels. Some years later, when I was a theater critic reviewing productions of Julius Caesar dressed in combat fatigues or Macbeth presented as a gangland bloodbath, I understood his point. Human passions such as greed for power, lust, and the compulsion for justice are universal, whether it’s Aegisthus, Clytemnestra, and Orestes; Claudius, Gertrude, and Hamlet; or a racketeer, a femme fatale, and a private eye unable to escape the moral imperative.

The other thing, of course, is what a fine writer Maclean was. We can best honor his memory by rereading his two marvelous books, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories and Young Men and Fire. The first is a jewel and a deserved classic. The latter, less well known but equally rewarding, is his reconstruction of a 1949 forest fire that killed 13 US Forest Service firefighters. It is a model of how to turn a carefully researched nonfiction account into a deeply moving story. Like A River Runs Through It, it is also a tough-minded, clear-eyed attempt to find meaning at the heart of a seemingly pitiless universe.

Jon Lehman, AB’62

Duxbury, Massachusetts

Rebecca McCarthy’s biography of Norman Maclean is an extraordinary achievement. It captures not only the Norman Maclean I knew as a grad student in 1970 but the much larger picture of the man in all of his complexity. Rebecca knew him long and well, I only briefly, as a student of Wordsworth in understandable awe of Maclean’s craggy presence and exceptional intellect—exceptional even in a place where exceptional was the norm. There’s a great deal in McCarthy’s book that I didn’t know, of course, and I am grateful for the broader and deeper view. It turns out that he was in fact a mortal being, who swore and drank, drove a Volvo, and used a Crock-Pot.

I believe Maclean would applaud this book’s honesty and comprehension of the whole man and the whole story.

It is also clear from this book that his, shall we say, direct approach to correction overlay a fundamental and sincere dedication to a student’s growth. I have my own tale to tell about that. Early on we were to do a two-page paper on Wordsworth’s “Westminster Bridge” sonnet. He was not impressed with mine. He said I should have used a .22 but I’d used a shotgun. I was devastated. He told me to come to his office on Friday. This was a Tuesday. For three days I wandered about like a zombie, assuming my graduate education was over in the first quarter.

On Friday, in his office at last after my Green Mile march from home, he poured me a cup of coffee, studied me for a long moment, and said, “Alm, you’re rusty. You have a fine mind, but you’re rusty after all that time in the Navy.” (I’d done two deployments in Vietnam, and just that April I’d been an engineering officer for the recovery of Apollo 13.) “The quick way to get rid of that rust is to kick it off.” That’s as I remember it. But the thing is, I never told him about the Navy. He had gone and checked me out!

Beyond an understanding of Wordsworth, which in retrospect was secondary, two memorable moments remain top of mind from that experience, 54 years ago. One, Maclean defined a good teacher as “a tough guy who cares very deeply about something that is hard to understand.” That was him, of course, but it gave the rest of us who were heading toward teaching careers a model. Two, he told us not to come into his classroom if we weren’t prepared to teach him something. That gave us to understand that this place was a community of scholars, and we had mutual responsibility to respect a high bar.

Rebecca McCarthy has captured all that brilliantly.

Brian Alm, AM’71

Rock Island, Illinois

The excerpt from Rebecca McCarthy’s book on Norman Maclean, along with its introduction, taught me much about someone I never met but to whom I feel connected. When James M. Gustafson, DB’51 (1925–2021), a Divinity School professor with whom I had come to study in the late 1980s, learned that I grew up in Missoula, Montana, he asked if I had read A River Runs Through It and Other Stories. When I confessed that I knew nothing of the book or its author, “Mr. G.” lent me his own copy, talked about Maclean, and fondly recalled his own days as a young minister in Montana before “being called” to graduate studies.

As I read the book, I thought of the many times that my father, a general practitioner in the days when doctors made house calls, and a dry-fly fisherman who tied his own flies, took us to fish in the Blackfoot River that “runs through it” and other waters probably familiar to the Macleans. Seeley Lake, so beloved by Maclean, was a frequent family vacation spot, and Young Men and Fire, which I read when it came out, reminded me of a grade-school field trip to the smoke-jumper training center at the airport a few miles from town.

Speaking at my father’s funeral a dozen years after A River Runs Through It reached the theaters, I shared memories of him with some help from Maclean. Afterward a physician friend of my father’s approached me, offered condolences, but had little good to say about the book and film. By making Montana trout streams so popular, they had ruined everything. I wonder how Professor Maclean, maybe turning to Shakespeare, or how the many students featured in McCarthy’s book, would respond to this complaint.

William George, PhD’90

Skokie, Illinois

Particle people

In “Atom Smashers,” Summer/24, you feature a photo of “chief betatron engineer Charles R. McKinney” putting a sample into a nuclear instrument. The nuclear instruments that Chuck McKinney became better known for were mass spectrometers that he built in collaboration with Professor Harold C. Urey, who in the 1950s was developing a new method to tell the temperature of the world’s oceans in the ancient past.

A collaborator on this work was Sam Epstein, who would soon be hired as a professor at Caltech, and who would take Chuck McKinney with him as technician in charge of building mass spectrometers.

As it happened, I also moved from the U of C to Caltech in 1953, where I became a grad student and research assistant in the lab where Chuck McKinney carried out his marvelous work. Without him, it would have been impossible to create the instruments that opened up the science of stable isotope geochemistry that came to be an important element of our understanding of Earth’s history. Chuck was a warm, open-hearted, and clever engineer, and we all appreciated his presence in the geochemistry lab. He authored a couple of scientific papers with Epstein and Urey featuring electronic circuit diagrams, something geochemists could hardly appreciate. Thanks for giving me that little memory of a lost hero of the struggle to understand Earth’s past.

Henry Schwarcz, AB’52

Jerusalem

I thoroughly enjoyed the article about the University of Chicago particle accelerators. I only wish it were longer. I’m particularly grateful for the picture of Professor Herbert Anderson, with whom I had the privilege of working as a postdoc for a few years.

Another student and I were the last to use the cyclotron in 1971.

After it was decommissioned, the magnet had another life. It was carried to Fermilab, where our University of Chicago collaboration with Harvard and Oxford used it to study quarks and gluons.

Howard Matis, SM’71, PhD’76

Berkeley, California

In Uncle Miltie’s footsteps

I was proud and pleased to see that Professor James A. Robinson won the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (Short List, 10.15.2024): the latest in a long legacy. When I was at UChicago, another Nobel Prize winner, Milton Friedman, AM’33, was a professor. My Economics 101 professor called Friedman “Uncle Miltie.” This was a reference to Milton Berle, for those of you who are not familiar with either Milton. This got a big laugh.

Vicky Thomas, AB’76, MD’80

Red Wing, Minnesota

For more on Robinson’s Nobel win, see “101 Acclamations.”—Ed.

I spy

My eye caught the photo on page 58 in the Summer/24 issue of the Magazine (“Focused Study,” Alumni News Snapshots). The standing woman is Maureen L. P. Patterson. I was a grad student in the early 1970s working on a dual degree in library science and South Asian languages and civilizations. Bob Emmett, AM’76, and I were Maureen’s advisees and interns, having embraced Indian studies as a result of our Peace Corps experiences there.

By the early 1970s, Maureen was known across the South Asian studies world as the woman who had made the University of Chicago Library the best South Asian collection in North America. She was wonderfully imperious and a force to be reckoned with. We grad students sort of knew Maureen had been in India when it became independent and in Delhi when Gandhi was assassinated. That was confirmed in 2009 when Bob sent me information about the book Sisterhood of Spies: The Women of the OSS. The ID card on the cover is Maureen’s. She must have been studying Japanese when she was recruited to the Office of Strategic Services to spy on the Japanese from a post in India. We learned much more from this book.

Shirley K. Baker, AM’74

St. Louis

People of letters

Several letters in the Summer/24 edition of The University of Chicago Magazine rang sympathetic bells with me.

Sandra Acker’s (AM’68, PhD’78) sadness and anger at the impending closure of the Department of Education in 1997 reminded me of similar feelings when Chicago’s world-class Department of Geography was allowed (and perhaps encouraged) to wither and die not long after I completed my studies there.

Mark Schlicht’s (MBA’78) account of snow and ice that kept his car frozen in place for days in 1977–78 recalled the great blizzard of 1967. That year Kenwood Avenue south of the Midway (my neighborhood, long since razed to the ground and rebuilt) went unplowed for weeks, reportedly because Mayor Richard J. Daley did not like our independent Fifth Ward alderman, Leon Despres. My VW bug stayed equally frozen in place for the duration of the great blizzard, so that my new wife and I had to trudge on foot seven blocks to and from the Co-op for provisions.

On a happier note (pun intended), Tom Shields’s (SM’82) memories of his time with the University Symphony Orchestra brought back my own love of fine music making with the orchestra, led then by Richard Wernick, with Leon Botstein, AB’67 (more recently president of Bard College), as concertmaster. In 1966 we even appeared on black-and-white TV on WTTW performing the Mahler First, with yours truly captured on bassoon in the “Frère Jacques” moment of the second movement. Many thanks, Sandra, Mark, and Tom, for prompting my recall of some memorable times!

Paul J. Schwind, AM’66, PhD’70

Honolulu

Seeking memories

I am a history student at the University of Memphis who is writing a biography of blues artist Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. On Thursday, May 18, 1967, Crudup gave his first real concert at Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago’s Rhythm and Blues Festival, which was held by the University of Chicago Folklore Society. I am hoping that someone has documents, photos, or memories related to his time in Chicago, or knows someone who does. I can be reached by email at cmllins7@memphis.edu or by phone or text at 901.288.0416.

Christian Mullins

Memphis, Tennessee

Corrections

In “Set in Stone” (Fall/24), we misstated dates in two photo captions. The photo of Old Chicago House was taken in the 1920s, and the illustration from the Medinet Habu temple complex dates from the Ptolemaic era (c. 145–116 BCE). We regret the errors.

The University of Chicago Magazine welcomes letters about its contents or about the life of the University. Letters for publication must be signed and may be edited for space, clarity, civility, and style. To provide a range of views and voices, we ask letter writers to limit themselves to 300 words or fewer. Write: Editor, The University of Chicago Magazine, 5235 South Harper Court, Chicago, IL 60615. Or email: uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu.